YIMBYs win, ‘Freeze the Rent’ and other ways housing is shaping NYC’s mayoral race

June 21, 2025, 9 a.m.

Housing affordability is the top issue for voters in New York City’s Democratic primary for mayor.

Back in 2021, as New York City emerged from the COVID pandemic, crime was on the rise, along with a deepening sense of disorder. Addressing those problems catapulted Eric Adams, a former cop, to City Hall.

Four years later, the Democratic primary for mayor is all about housing.

Multiple polls show housing affordability is the top issue on voters’ minds as rents soar, sale prices make it impossible to buy homes, costs rise for landlords and rental assistance remains out of reach for most people.

The mayoral candidates have responded with an array of proposals and policy plans focused on supercharging development and curbing rent increases, though they differ in their approaches.

Here’s how housing affordability is shaping the political landscape:

YIMBYs win the culture war?

The city’s most recent housing survey paints a grim picture: Fewer than than 1% of apartments priced below $2,400 a month are empty and available to rent. More than half of all New Yorkers are considered rent-burdened, meaning they spend at least 30% of their incomes on housing.

This is one issue where candidates for mayor agree on a solution: Build, baby, build.

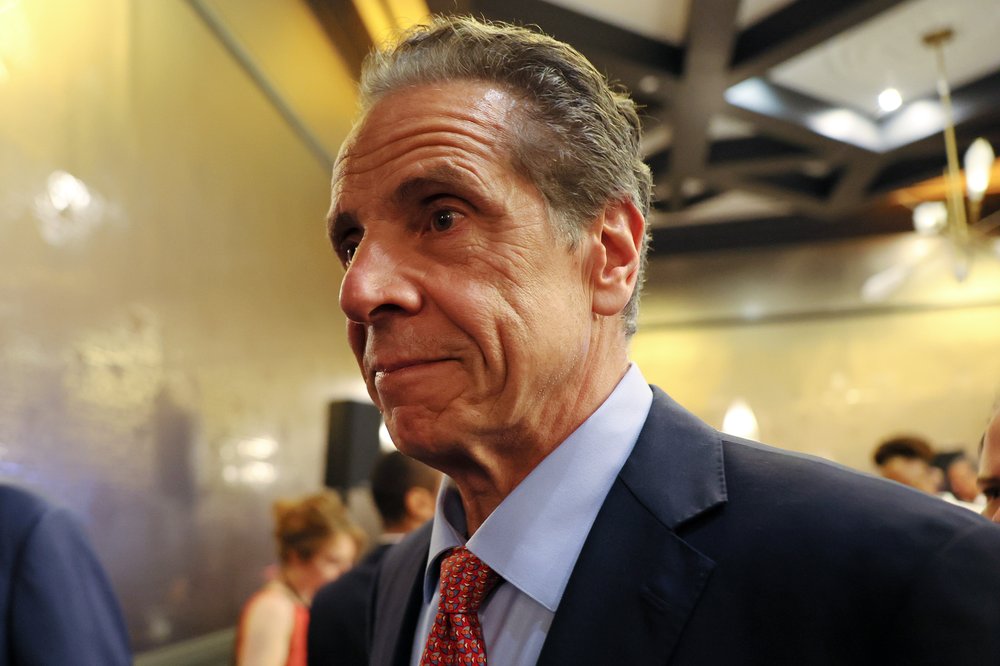

First, the raw numbers. Assemblymember Zohran Mamdani said he’d create 200,000 units priced for low- and middle-income renters. Ex-Gov. Andrew Cuomo wants to deliver 500,000 new homes, the same “moonshot” figure announced by Mayor Adams early in his tenure. But why stop there? State Sen. Zellnor Myrie’s plan calls for the creation or preservation of 1 million homes.

Whatever the feasibility of those plans — and we’ll get to some of the details in a moment — Democrats of all stripes are emphasizing housing production. And that’s an “enormous shift” from the past, said Annemarie Gray, executive director of the housing advocacy group Open New York.

“Four years ago, it would have been inconceivable to see every mayoral platform across the spectrum include building more homes more quickly,” Gray said. “It’s no longer controversial.”

But their approaches differ.

Mamdani, from Astoria and a democratic socialist, says the private market plays an important role in new housing construction, but he wants to put the public sector in charge. He has said he would commit $100 billion over the next 10 years to finance 200,000 new units that are affordable for the lowest-income New Yorkers.

His plan depends in part on other levels of government. Mamdani has said he would push state and federal lawmakers to let New York City take on additional debt and issue more bonds to fund development. Such proposals have support from a range of housing advocates and policymakers but have so far failed to gain traction in Albany and Washington. State and federal rules limit the amount of bonds the city can sell to investors to raise money for affordable housing.

Moderate rivals, like Cuomo and hedge fund manager Whitney Tilson, have attacked the plan, saying it’s unlikely to happen, and that even if it were possible, all that borrowing would jack up the amount of money the city pays in interest.

Cuomo instead wants to make it easier for the real estate executives spending millions to boost his campaign to build large projects that qualify for a state tax break program known as 485-x. The program requires developers to reserve a quarter of new units for low- and middle-income renters and to pay higher wages to unionized workers for any project of 100 or more units. But so far, developers operating under the tax break program haven’t applied to build anything bigger than 99 units, so as not to trigger the wage increases.

All of the candidates say they want to supercharge housing on public land.

Comptroller Brad Lander wants the city to build 50,000 new units on four of the city’s 12 public golf courses. Which one would depend on a feasibility study, he said. Scott Stringer wants to conduct a comprehensive audit of city-owned properties, something he did as a comptroller, and then give the land to developers to build new mixed-income housing.

Myrie said the city could add nearly 100,000 new homes on land owned by the New York City Housing Authority, a concept known as infill. Most candidates say they would support private development on the campuses — a proposal that is already underway at the Fulton and Elliott-Chelsea Houses in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood.

Council Speaker Adrienne Adams focused on the topic in her 2023 State of the City address and said new buildings constructed on NYCHA grounds would include new apartments for public housing residents as well as “other city- and state-funded affordable and mixed-income units.”

Cutting red tape

Candidates like Lander, Myrie and Cuomo also want to cut through a thicket of regulations, especially as they relate to low- and middle-income apartments.

Lander, a former councilmember, would declare a “housing emergency” and suspend the city’s lengthy land use review process. He said he would propose a new procedure that takes less than half the time as the existing one and push for “comprehensive planning” to determine where and how much new housing gets built.

Myrie would legalize smaller elevators and allow more buildings to each include a single staircase, thereby freeing up space for more units — a favorite topic of pro-housing advocates that raises safety concerns among fire officials. And Mamdani said he would eliminate parking mandates that take precious space away from actual housing units.

Cuomo has used the two mayoral debates, including one cohosted by WNYC, to call for a complete overhaul of the city’s housing agency, the Department of Housing Preservation and Development, to make it more efficient.

Some of these ideas could actually appear on the ballot this November, alongside the people running for office.

Mayor Adams tasked a commission with proposing changes to the city’s charter, its governing document, that would eliminate regulations or bypass opponents of new development — like councilmembers who block housing in their districts. Voters will likely see some of the commission’s final recommendations on the general election ballot.

No neighborhood left behind

Under then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg, the city changed land use rules to restrict new housing development in dozens of suburban-style neighborhoods in Brooklyn, Staten Island and Queens. A 2024 report from the Citizens Housing & Planning Council found those “downzonings” prohibit new multifamily housing in an area the size of Manhattan.

Mayor Adams tried to reverse this trend through a major land use overhaul dubbed the “City of Yes.” The plan was meant to allow, as the current mayor has frequently said, “a little more housing in every neighborhood.”

Many of the candidates trying to replace him — including Mamdani, Lander and Adrienne Adams — say they want to continue those efforts and produce more affordable housing in parts of the city where construction is scarce, especially the richest neighborhoods, like the Upper East Side, and lowest-density neighborhoods, like Northeast Queens and Southern Brooklyn.

Adrienne Adams has argued that she’s already doing this work as City Council Speaker. She’s touted her “fair housing framework” legislation that sets housing production targets for every community district as well as her key role in winning approval for the mayor’s rezoning plan.

Cuomo, in contrast, would take a Bloombergian approach by targeting more development in densely populated parts of the city while giving a free pass to single-family homes and properties with big backyards.

Freeze the rent?

It’s a battle cry that conjures another campaign slogan of yore: “The Rent is Too Damn High.”

The phrase “Freeze the Rent” is a big factor in this year’s race for mayor, and the body with power to actually freeze it has been thrust into the spotlight like never before.

That body is the Rent Guidelines Board, and its annual vote on rent increases for about 1 million regulated apartments coincides with the primary. The panel of nine housing experts, all appointed by the mayor, will make that decision on June 30.

Their vote has never before been such a prominent part of a mayoral race,

“I don’t remember a time when the Rent Guidelines Board affairs were so central to a mayoral race,” said Timothy Collins, a former executive director of the board who wrote its official history. “I don’t think there is a precedent.”

Mamdani launched his campaign last October with a promise to appoint a board that will never raise rent during his tenure.

“We’re seeing rent hike after rent hike and this can be the difference for many New Yorkers on whether or not they can afford to live in the city anymore,” Mamdani told Gothamist outside a preliminary vote by the board in April. “I think it’s unacceptable. I think it’s unconscionable and I would bring it to an end.”

Mamdani was arrested while protesting the board’s vote last year. Now, every Democratic candidate other than Cuomo and Tilson have joined the call — to the chagrin of landlord groups who say they need to increase rents to keep up with their own rising costs, and to continue making a profit.

Board members voted to freeze rents three times under Mayor Bill de Blasio. Collins called that a “notable contrast” to their decision to increase rent by a combined 9% under Adams.

That contrast, he said, "illustrates the role the mayor has over the appointments,” Collins said.

As NYC moves forward with Chelsea plan, senior residents brace for relocation 'No excuse': Local officials urge Hochul to collect millions in Atlantic Yards penalties Federal judge clears way for NYC broker fee ban to begin