What Would 'No New Jails' Actually Look Like?

July 16, 2019, 3:05 p.m.

Prison abolitionists admit they aren’t offering a plan to shutter New York’s jails tomorrow. But they see enough promise in alternatives to incarceration to hope a jail-free New York could become a reality.

On the evening of June 25th, a group of New York prison abolitionists gathered inside the hearing room of Bronx Borough President President Rubén Díaz Jr. to hear City Hall’s proposal to replace Rikers Island with “a network of modern and humane borough-based jails” in the Bronx, Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens. During the presentation by the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice, members of the crowd hoisted up green flyers declaring “If They Build It, They Will Fill It.” For several hours, organizers went up to the microphone to testify, many using “No new jails!” as their rallying cry.

Later that night, at La Boom nightclub in Queens, the slogan emerged again as a chant after Tiffany Cabán—who had campaigned as a “decarceral” prosecutor, promising to oppose construction of new jails, end cash bail, decriminalize sex work, and put far fewer people in prison—declared victory in the race for Queens District Attorney. (The race is now in recount.) A few weeks later, the chants of “No new jails!” were back at a City Planning Commission hearing, drowning out speakers and briefly halting the proceedings.

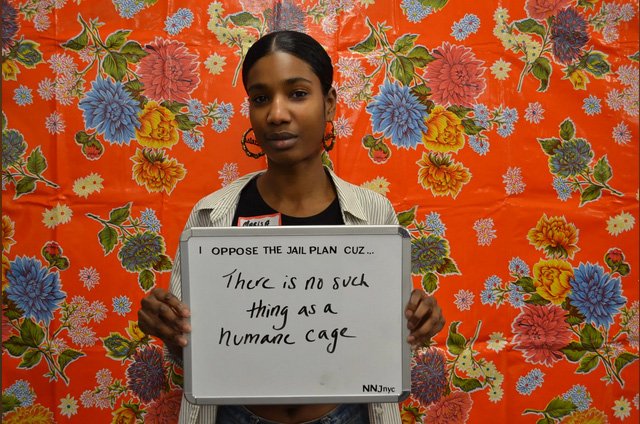

It’s been a rapid rise to prominence for the prison abolitionists of New York, who first organized only last September as a coalition known as No New Jails NYC. Since learning that the city planned to replace Rikers Island with a borough-based jail system, the group’s goal has been to promote a vision of a different kind of future, one where incarceration is wiped from the American landscape. In New York City, support for the cause is suddenly ringing out in public hearings, political campaigns, and the pages of The New York Times Magazine.

As abolition increasingly enters New York’s public consciousness, there remains an obvious question: Can we really become a city without a jail system? And if New York ever embraced abolition as a goal, how would we actually get there?

No New Jails advocates admit that they aren’t offering a plan to magically shutter New York’s jails tomorrow. But they see enough promise in alternatives to incarceration to hope that a jail-free New York could be a reality sooner than later.

“Just recently, people thought we were out of our minds,” says Pilar Maschi, a Bronx-based abolitionist. “But abolition is contagious. It’s idealistic, and I’m okay with that. I think we should strive for what we want, not just accept what we have.”

City rendering of a proposed 45-story jail on White Street in Manhattan. (Mayor's Office)

New York City’s Department of Correction oversees the city jail system, which is designed to hold those awaiting trial or serving short sentences. Longer sentences are served in prisons, most of which are located upstate.

Currently, the city contains 11 operating jails—eight facilities on Rikers and three in the boroughs—with 11,300 beds total. The plan to close Rikers would reduce the city’s bed count to 4,600, while lowering the number of incarcerated people from roughly 7,500 to 4,000.

Abolition, as described by prominent New York abolitionist Mariame Kaba, is grounded in the belief that white supremacy is maintained and reproduced through criminal punishment, making reform of the current system impossible. It is a vision of dismantling the country’s entire criminal justice system as it exists today, with those most affected by policing and mass incarceration re-imagining new solutions that make communities safe while addressing societal inequities.

“We are building something that does not exist at this point in time,” Maschi says.

With the U.S. imprisoning more people than any country in the world, abolition and proposals of “transformative justice” are increasingly gaining traction. San Francisco has set a goal of closing its youth detention facility by 2021, while Los Angeles is demolishing its central jail and replacing it with a mental health center.

In New York, jail admissions have been reduced to less than 40,000 per year, a roughly 50 percent drop since Mayor Bill de Blasio took office in 2014, according to a Tuesday press release from the mayor’s office. But it was the mayor’s proposal last August to replace Rikers with humane “justice hubs” within communities and near courthouses that inspired a local abolitionist movement.

Kaba has said she’s working toward a goal that won’t be achieved in her lifetime. Rather, the “no new jails” message serves as a plea for the city to instead invest in alternatives, whether stable housing, restorative justice, or reparations.

It’s a unique argument, to be sure, to make at a community board or public planning hearing. But No New Jails organizers believe it’s a powerful one amid greater opposition to the jail plan.

“People don’t want to go to jail, and people don’t want a jail,” says No New Jails organizer Samantha Johnson. “So how do we make this happen, if you don’t want a jail in your backyard messing up your azalia bush? Can you give them a job, give them access to the support they don’t have, can you become a friend to them?”

The question of whether to build new, smaller jails or try to eliminate them entirely has split the movement to close Rikers Island. (Scott Heins / Gothamist)

At the same time, the No New Jails vision has caused tension with other advocates for closing Rikers. The campaign has arrived at the same time as community boards, borough presidents, residents who would live near proposed jails, and people formerly incarcerated on Rikers have raised objections to the proposal for new jails. It’s resulted in a tense public hearing process that’s left the fate of the mayor’s plan uncertain: All four impacted community boards have cast advisory votes against the new jails, but actual approval will be up to the City Planning Commission and city council in votes this fall, and the four councilmembers whose districts include the jail sites have so far indicated they tentatively plan to vote yes.

“There’s a whole conversation of ‘this is abolition, this is not abolition,’ or what is pure abolition,” says Brandon Holmes, New York City Campaign Coordinator at JustLeadershipUSA, which supports the mayor’s plan but wants him to go further to rein in abusive policing and involve affected communities in the work to close Rikers.

“We are talking about abolishing eight facilities to have four facilities,” Holmes says of the borough-based replacement plan. “We’re talking about rebuilding and improving conditions to create facilities that can actually serve people who are there. This plan is a tangible path forward that commits to further decarceration than we are currently at.”

JustLeadershipUSA runs the #CloseRikers campaign, which supports reducing prison capacity through borough-based jails and decarceration methods like overhauling pre-trial detention (over half of people awaiting trial in New York’s jails are there because they can’t afford bail); eliminating city sentences of one year or less and replacing them with alternatives like community service; revamping the parole supervision system; and decriminalizing low-level, non-violent crimes like turnstile jumping. Combined, these efforts could free around 5,000 people, according to #CloseRikers.

No New Jails organizers also support a range of decarceration methods, with an emphasis on eliminating pre-trial detention. The sticking point, for #CloseRikers organizers, is that No New Jails fails to offer a concrete plan to full decarceration. Because abolition exists in a future that can feel far away—if not impossible—it’s a criticism that prison abolitionists are no stranger to.

“We have a plan, our community members are building that for us,” Johnson says. “When a person is saying, where do people go?—well, they go home. They go to institutions that are supposed to rehabilitate them. We have to think about where people can go and find resources that support and create a platform for their success. Our systems were not built for success.”

One No New Jails organizing tactic is to focus on the sheer amount of money the city invests in its current systems—and propose redirecting it to communities instead. On top of the $8.7 billion price tag for new jails, last year’s City Department of Corrections budget rose to $1.39 billion, and the average annual cost per inmate for the first time surpassed $300,000.

No New Jails organizers do not have a hard time envisioning where billions of dollars could go in a city grappling with wealth inequality, an affordable housing, public housing, and homelessness crisis, inadequate mental healthcare, and a deeply segregated school system. And they often suggest these citywide concerns have made other New Yorkers more open to the idea of abolition.

Protestor outside Queens criminal court, October 30th, 2018 (Scott Heins / Gothamist)

Even beyond funding things like stable housing, economic, and educational opportunities—the lack of which can drive crime—a growing number of New York organizations are already working on strategies for transformational justice and alternatives to incarceration. “We understand that harm and conflict happens,” Maschi says. “Meeting those needs and providing resources so people aren’t harming people is really important to abolition.”

Kerbie Joseph is a No New Jails organizer who works with Audre Lorde Project to run Safe Outside the System, an LGBTQ anti-violence program. In the early 2000s, organizers developed de-escalation tactics that community members and local businesses can use without calling the police. Today organizers trained in de-escalation promote community safety at events and protests and in homes. Another program called 3rd Space provides support around employment, education, healthcare, and immigration status.

“There is a multi-, multi-billion-dollar budget [for enforcement and incarceration]—but imagine if part of that budget was removed and given to organizations like Audre Lorde,” says Joseph.

Violence interrupters are another form of community-specific organizing effective across New York. A 2011 city council pilot supported the program, which trains carefully selected community members in high-need neighborhoods to anticipate where violence may occur and intervene before it erupts. Violence interrupters couple that work with outreach and education.

One result of the pilot is Brownsville in Violence Out (BIVO), in which an 11-member team works with young people involved with or at risk of gun violence and gangs and provides wraparound services like job training, health awareness, and conflict mediation. The group began its work in 2015 in an area with high gun violence between residents of two public housing developments.

Anthony Newerls, the program manager, credits violence interruption with the decline in gun violence at the two developments: last year BIVO's focus area, which is within the 73rd precinct, went 382 days without a shooting, followed by 121 days this year. In 2018, NYPD data showed 13 homicides in the overall 73rd Precinct, none of which occurred in BIVO’s zone.

“I would love to see the program expand, to bring on more staff and do more outreach in the community,” Newerls says. “I’d like to see more funding and support, just so we could do more.”

There are also effective alternatives to incarceration within the city’s court system. In 2015 the Center for Court Innovation launched Project Reset as a diversion network that allows young people arrested for low-level offenses to avoid court or prosecution. It has since expanded to serve people of all ages across Manhattan, Bronx, and Brooklyn.

Most people invited into the program agree to participate, with 98 percent fulfilling obligations of community-based programming, according to Adam Mansky, director of criminal justice for the center. A 2019 analysis found participants were re-arrested at a lower rate than a comparison group (14 percent vs. 17 percent) and were less likely to have a new violent felony arrest within the next six months (0 percent vs. 2 percent). And since the participants never appear in court, their original arrest paperwork is sealed, no cases are ever filed, and there is no criminal court record of the cases.

The center also offers a Peacemaking restorative justice program based on a model of justice used by the Navajo Nation, though similar methods are used by the Muskogee Nation and several Native American tribes in Oregon. A trained community member brings those affected by a conflict, alongside family and neighbors, to sit in a circle to discuss the conflict’s underlying causes and what it will take to heal. Defendants are referred by a judge, prosecutor, or defense attorney; once they successfully complete the program, they will typically have their case dismissed.

A 2015 report by Peacemaking in Red Hook found both defendants and crime victims generally supportive of this method, perceiving it as a positive impact on the lives of participants and the community.

Similar work is carried out by Brooklyn-based Common Justice, the first alternative-to-incarceration victim-service program in the country focusing on violent felonies in the adult courts. The work inspired Common Justice founder Danielle Sered to publish a book, Until We Reckon, breaking down how U.S. jail and prisons fail to make communities safer.

“Incarceration is a limited tool because it treats violence as a problem of ‘dangerous’ individuals and not as a problem of social context and history,” Sered writes. Her book makes a case against incarceration’s punishment model and for new, more restorative methods of accountability for violent offenders.

On a hot Sunday afternoon this June, the uphill battle to dismantle the system was made clear. A group of roughly 20 met in a Bronx community garden—a peaceful pocket of green despite the Bruckner Expressway towering overhead—to talk about lessons learned from successful organizing against a $375 million jail proposed in 2006 for the South Bronx.

Organizers were hopeful they could repeat that success. But at one point, they pulled out a sheet of butcher paper to identify both supporters and detractors of the No New Jails platform. The list of opposing politicians, nonprofits, and community groups grew longer and longer.

Ultimately, prison abolitionists counter the city’s detailed proposal of how to close Rikers with a question: What would New York look like with funded social services and stable housing, without segregated schools or ICE detention, and with money funnelled into transformative justice? They don’t want to settle for anything less.

“It is possible and we can’t keep thinking it isn’t,” says Johnson. “It’s not that abolition is a unicorn. It’s not just a theory. It’s a practice and we have to practice it in order for it to be real.”

Correction: This article originally misidentified the name of the agency that oversees New York City's jail system. It is the Department of Correction, not the Board of Corrections.