What It Will Take To Bring Strong Internet Service To Every NYC Student

May 13, 2021, 3:28 p.m.

New plans have emerged from the feds, state, city and grassroots efforts.

Over the past year, the pandemic has laid bare some of the deepest inequities in education. Chief among them: the digital divide between students with reliable internet access in their homes, and those without. Now, as politicians pledge to rebuild the school system better, and stimulus dollars create new opportunities to address long-standing problems, advocates for high-speed internet access for everyone hope solutions may finally be in reach.

On Wednesday, the Biden Administration began making new emergency grants available for low-income families to offset monthly broadband costs. New York City is seeking to partner with private companies and boost competition to drive down prices. New York State just passed a law requiring internet companies to offer a $15 monthly high-speed option to low-income households. Last week, a coalition of city activists launched a campaign to mobilize support for municipal broadband. Local residents are banding together to wire their own networks from neighborhood rooftops.

“It is a transformative moment in digital equity because there’s an awareness and a visibility of this issue that there’s never been before,” said Greta Byrum, Director of Policy at the nonprofit Community Tech NY and co-director of the Digital Equity Laboratory at the New School. “We’re seeing incredible creativity and innovation.”

The Extent of the Problem

More than a million New Yorkers don’t have access to broadband in their homes right now. When the pandemic hit last year, the number was even higher. As soon as schools went remote last spring, stories poured in of students’ struggles to get online. A teenager spent hours slumped outside her neighbor’s doorway trying to get a signal for her laptop. Kids camped outside McDonalds to grab Wi-Fi. Siblings had to take turns going to school on a parent’s iPhone.

“I’ve had students whose families had to choose between paying for Wi-Fi or paying for groceries,” said Brooklyn elementary school teacher Martina Meijer. “I’ve had students whose families had to choose between paying for Wi-Fi and paying rent.”

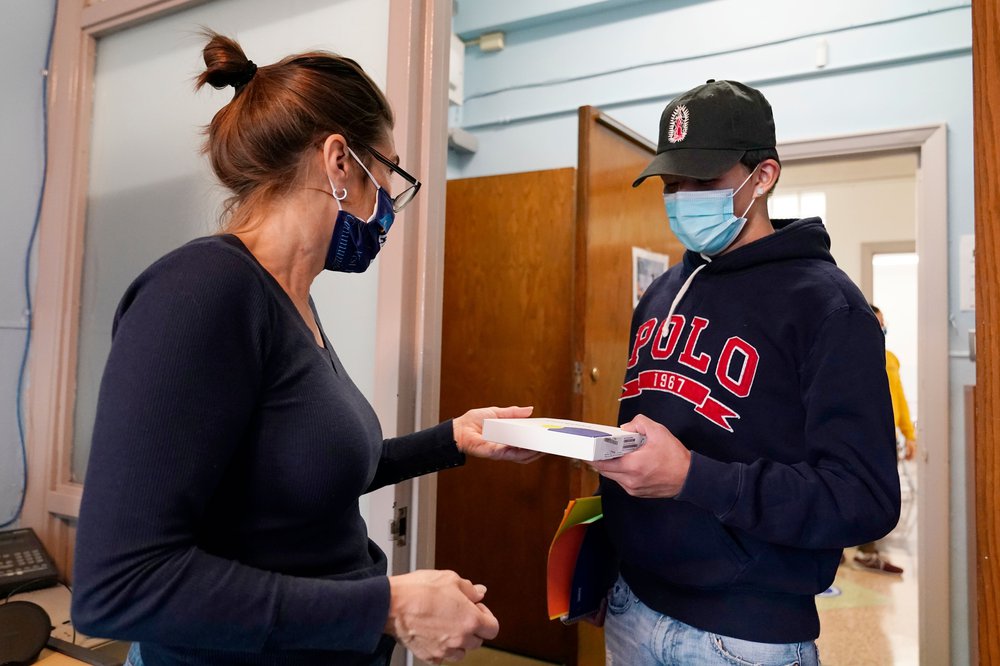

As the city locked down, officials mobilized to equip kids with devices, an effort that ultimately spanned nine months. It distributed more than 500,000 tablets with cellular service. At about $875 per device—inclusive of delivery, setup, support, and a case—the total investment amounts to an enormous sum, $437.5 million.

The tablets created an essential link to school for many students. But for some, the signal wasn’t strong enough for Zoom meetings or Google Classroom. The tablets were hard to type on. They often didn’t work in basement apartments. Some broke.

“It’s written in the law that our kids have a right to public school education,” said Tom Sheppard, the elected parent member of the city’s Panel for Educational Policy. “And during this pandemic, if you are not connected to the internet, you are not connected to your school, and therefore you’re not getting the public education that you are entitled to.”

So why doesn’t NYC have the ability to connect the entire city, let alone its nearly 1 million students?

Access and Affordability

The infrastructure for the internet dates back more than a century, when the federal government allowed telecommunications companies to build electric, phone and eventually cable lines in return for a promise to connect all residents.

There are a handful of internet providers operating in New York City, but two “legacy” telecom companies—one phone, one cable—dominate the market. Some universal broadband advocates refer to Verizon and Spectrum as the “Duopoly,” even as smaller startups have entered the market.

According to critics—a group that includes activists, experts and city officials—top providers have prioritized neighborhoods with higher-income households, because the residents there are most likely to pay top dollar for high-speed service.

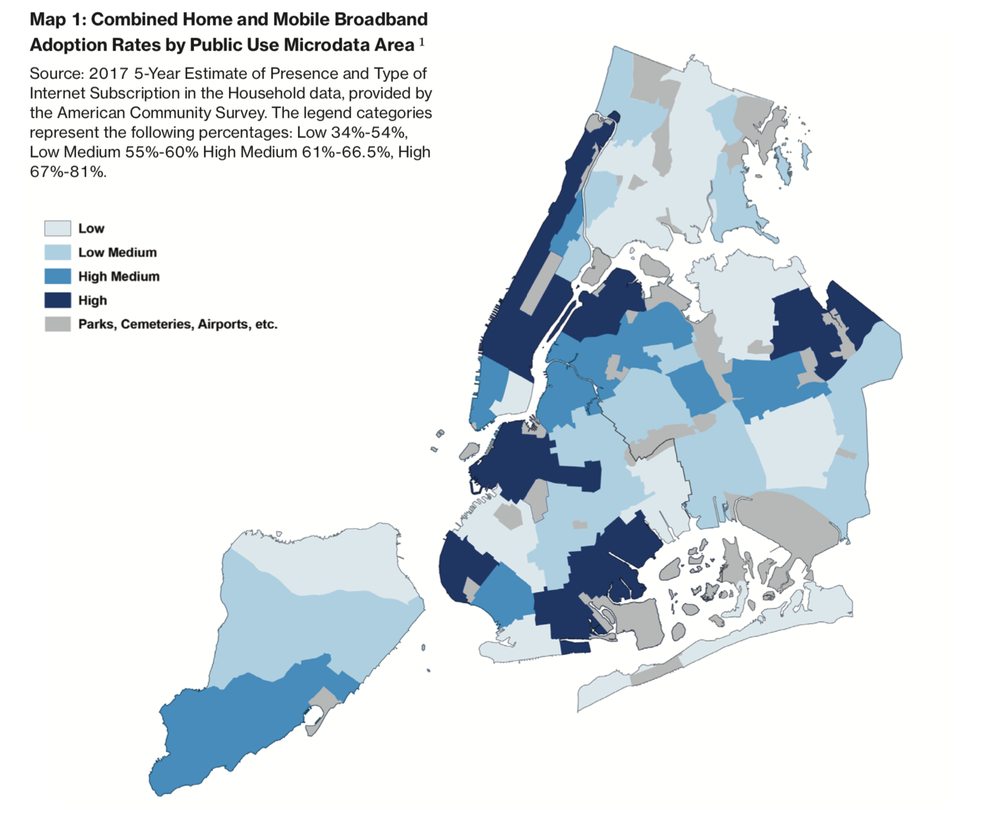

Low-income communities of color tend to have fewer connections to high speed internet, and smaller numbers of providers serving them, meaning consumers can’t shop around for better deals. Some call this ‘digital redlining,’ and maps of internet access in the city largely mirror the redlined maps from the Federal Housing Administration in the 1940s. Service maps also track with local poverty rates. According to the New York Urban League, 61 percent of Latino New Yorkers, 66 percent of Black New Yorkers, and 79 percent of white New Yorkers have used broadband at home.

Companies argue cost drives these geographic decisions. “The carriers would tell you it’s incredibly expensive, incredibly difficult, and time-consuming to build out infrastructure across New York City,” said Julie Samuels, executive director of Tech:NYC, an industry group that represents technology companies. “It’s not a streamlined process at the city level. You need to work with the city for all kinds of rights of way, literally you’re talking about digging up sidewalks and putting wires on light poles.”

She said it’s often “the last mile” that provides the most challenges. Companies have to work with landlords to get fiber from the ground into buildings and into units. “All these things are pieces of the puzzle,” she said.

In 2008, Former Mayor Michael Bloomberg tried to address gaps in high-speed service by striking a deal with Verizon to extend FiOS throughout the city. Several years later, the de Blasio Administration sued the company for failing to follow through. Last fall, Verizon and the city agreed on a settlement: Verizon would wire 500,000 more households with high-speed internet by 2023, starting with 11 public housing developments.

But Samuels said the biggest challenge isn’t physical access to wires in the streets, it’s getting those wires into households, and ensuring service is affordable. “The technology is not actually the hard part,” she argued. “It’s cutting through the city’s red tape and fostering competition among carriers to bring costs down for customers.”

The average monthly cost of broadband service is over $50 per month, which, officials said, can be a big chunk of a poor household’s monthly budget.

Internet providers, including Spectrum and Verizon, do sell discounted plans to low-income families. But the companies typically require credit checks, which can be an obstacle for poor households. Some smaller companies avoid credit checks to encourage more families to sign up.

As schools went remote last spring, several providers offered free service to students, though some blocked students from getting online if their families had unpaid bills before quickly reversing those policies.

Latest Plans to Close the Gap

Biden’s Broadband Initiative:

The most recent stimulus bill included $100 billion for broadband, but that’s largely targeted to rural areas. But the Biden Administration is proposing another $100 billion for broadband as part of the infrastructure bill currently before Congress, which would prioritize nonprofit and municipal plans. This week, the federal government began partnering with providers to offer a monthly discount of up to $50 called the Emergency Broadband Benefit for low-income families, which will sunset when money runs out. The challenge, universal broadband advocates said, will be finding a way for families to continue to afford service when it’s no longer subsidized.

Cuomo’s Low Cost Mandate:

In April Governor Andrew Cuomo signed legislation requiring private companies to offer families a $15 option for internet service to qualifying low-income families. The governor said the law would provide affordable internet to seven million New Yorkers. Experts note that many providers already do offer lower-cost plans. The issue is whether those plans come with the high speeds students need for school, and whether they require credit checks that keep some consumers from adopting service. Within weeks, large telecommunications companies, including AT&T and Verizon, had sued the state over the new law, making its fate unclear.

New York City’s Master Plan:

Just before the city locked down last March, officials released a blueprint for comprehensive broadband access called the Internet Master Plan. It envisions a patchwork of initiatives to reach every intersection and each corner of the city. The goal is to increase competition between internet providers in order to drive down prices, support small businesses, and create jobs. To do so, the city would make its own real estate—like rooftops and light poles—available to private companies willing to extend wiring and supply residents with lower-cost service. The city would also buy or build some infrastructure itself to increase access and competition. Additionally, the city is partnering with companies to wire public housing, support community-based networks, and expand Wi-Fi in public spaces.

“There is no one single solution that solves the whole problem,” said John Paul Farmer, New York City’s Chief Technology Officer. "Instead, what we have identified is a collection of technologies, companies, and organizations—in addition to direct government action—that together give us what we need."

Experts agree that the multi-faceted approach makes sense and that increasing competition to drive down costs is key. Still, some critics have said the city’s roadmap repeats previous mistakes by relying too heavily on private companies.

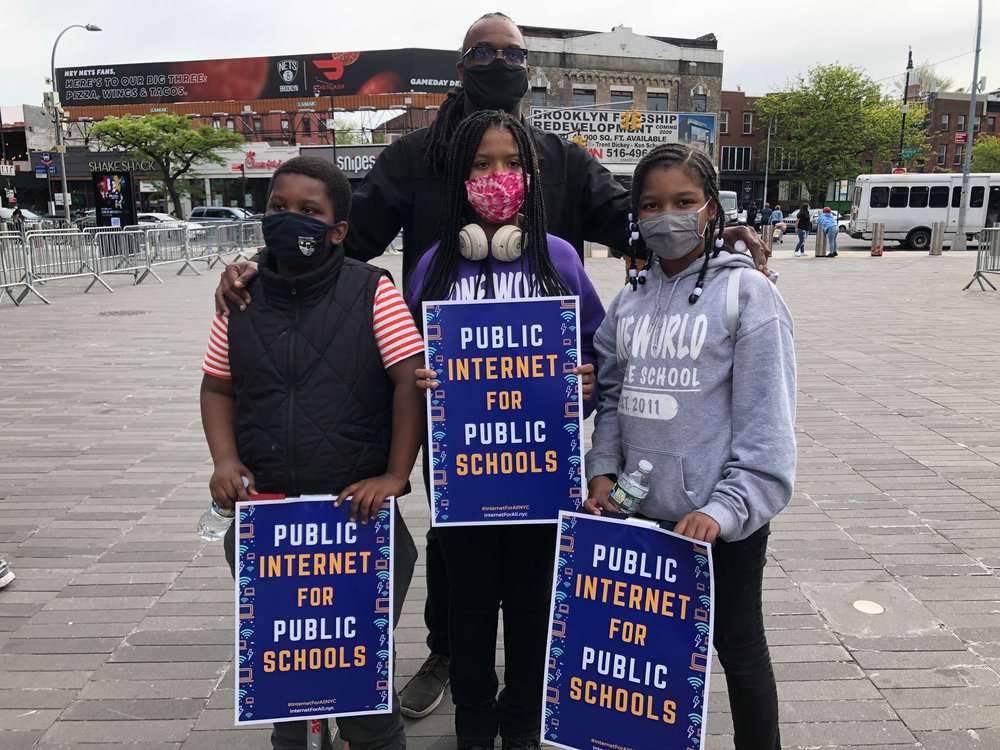

The Push for Municipal Broadband:

A group of activists, educators, and striking Charter/Spectrum workers, called the Internet for All Coalition, wants the city to form a new municipal agency to connect fiber networks to underserved neighborhoods and operate service at low costs. As a model, advocates point to Chattanooga, Tennessee, a pioneer in public broadband, where the city made high-speed internet available to residents at lower costs than the large private provider. Skeptics have said the plan is unrealistic for New York City because it would require the formation of a new arm of government to build, maintain, and operate the network, which would be extremely expensive and politically challenging.

Community and Mesh Networks:

Community groups throughout the city have been launching their own free Wi-Fi networks using small devices placed on buildings or in windows. There are mesh networks in the Bronx, Harlem, Red Hook, and Rockaway. Often volunteer-led and low-cost, the initiatives are a nimble way to expand service in areas without it, but speeds are variable.

The Path Forward

All the leading mayoral candidates have said on their websites that they would push for universal high-speed internet, with varying degrees of detail. A few of the candidates participated in a recent mayoral forum hosted by the Educational Alliance and Tech:NYC. Shaun Donovan said he would offer grants to providers to serve ‘internet deserts.’ Kathryn Garcia pledged to streamline bureaucracy and encourage collaboration between companies. Ray McGuire said he would leverage relationships with tech leaders. Scott Stringer promised “internet passports” in the form of subsidized service for all low-income students.

Officials said they’re hopeful families won’t have to rely exclusively on the internet to attend school next year. Mayor de Blasio is promising to welcome back any student for in-person learning full time in the fall. But he has also indicated there will be a remote option for students who don’t feel comfortable coming back to buildings in September. Instead of days off from school, remote learning days are already planned for Election Day on November 2nd, and any snow days. There is no doubt kids will continue to need strong internet access after the health crisis subsides.

“I hope that all kids are back in school next year, but I also hope that we’re able to keep the pressure on this issue even if we’re not in zoom school,” said Samuels of the industry group Tech:NYC.

The New School’s Byrum said that each of the initiatives underway are imperfect but contain seeds of solutions. “Think of it like a garden, you have to weed over here, plant over here, water over here,” she said. “This is a structural problem like climate or racism... It can feel really daunting, like any structural issue, if you want a simple solution. But this is the work of our lifetime. And New Yorkers love a challenge.”