Upstate NY groups demand Hochul stop delaying decision on Bitcoin gas plant with expired permit

Aug. 11, 2025, 10:32 a.m.

The state environmental agency denied a cryptomining company an air permit three years ago. It's been running ever since.

The state denied Greenidge Generation a permit 3 years ago. It's been running a natural gas plant ever since.

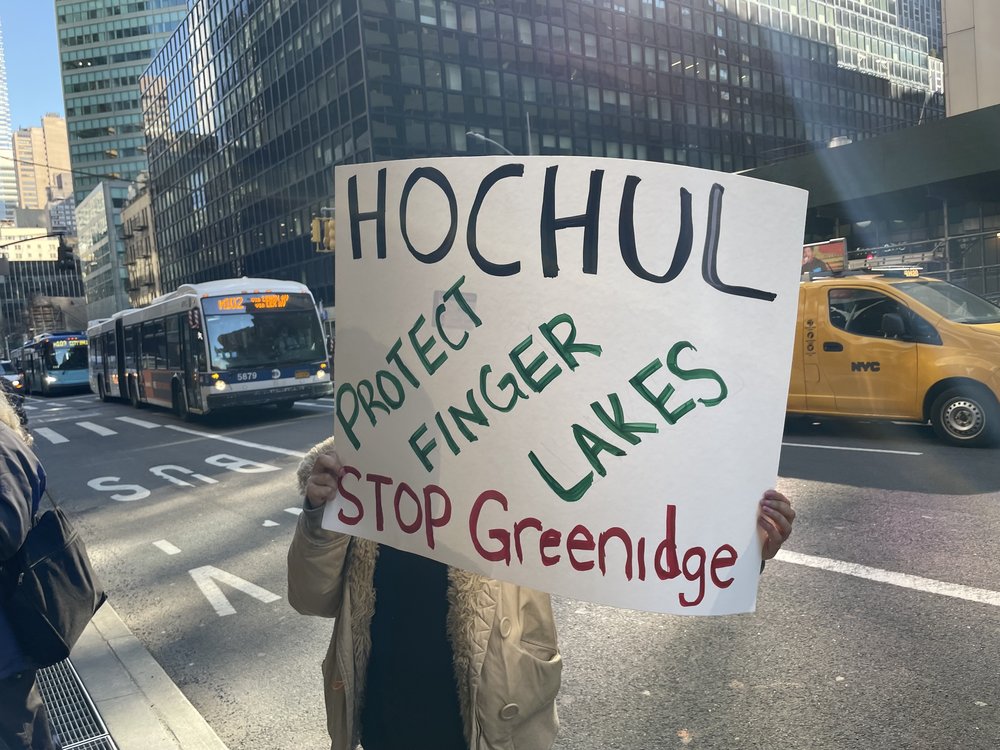

A group of Finger Lakes residents say they’re fed up and taking action against a local cryptomining company as it continues to operate a gas-fired power plant, despite being denied an air permit more than three years ago.

The state Department of Environmental Conservation rejected Greenidge Generation’s permit to operate a natural gas plant in 2022. Three years and thousands of Bitcoins later, Greenidge is doing a brisk business, emitting around a half-million tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere each year, according to the DEC.

The fight in the Finger Lakes has been going on for years and was a forerunner to battles now emerging across the state and nation as server farms crop up from New York to California, often sapping the local electric grid or firing up retired gas-burning plants. With the Trump administration’s all fossil-fuel energy strategy — and years of bureaucratic delays — residents say they need the state to act.

”We are beyond frustration and disappointment,” Vinny Aliperti, who owns and operates local vineyard Billsboro Winery, said. “This should have been a slam dunk.”

Greenidge has made more than $200 million in revenue since its air permit was denied in 2022, according to company filings. In denying the air permit, state officials said the company did not demonstrate a credible plan to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions, as required under the state’s Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act.

Greenidge appealed the decision with the DEC and local courts and was allowed to keep operating. After a series of delays and legal maneuvers, the case is back before the department’s administrative law judge. Local community members and groups said they’ll file a motion Monday asking to conclude the evidentiary hearings by the end of the year.

Environmental groups said a hearing scheduled for last week was postponed for a third time, by about three months, prompting their motion. They said the delays were a “long-term strategy to drag out proceedings in court,” according to a draft of the motion reviewed by Gothamist.

Greenidge denied that accusation.

“Any statement that suggests Greenidge desires to delay this process further would be actionably false and asinine,” company president Dale Irwin wrote in an email.

The company has said Albany’s limited hearing space makes scheduling difficult. The motion by local environmental groups offers alternative locations for the hearing, including the law offices of Greenidge’s lawyers.

In a letter to the judge, Greenidge attorney Yvonne Hennessey said she was too busy due to other projects to attend the hearing originally scheduled for June, and required a postponement. Most recently, the company asked for a postponement due to the Hochul administration’s release of a draft energy plan, which cited the need for continued reliance on fossil fuels and more investment in related infrastructure. Greenidge requested more time to review the state’s plan as potential justification for its operations.

Between that and the bureaucratic delays by the DEC, local activists say they’re losing patience with Gov. Kathy Hochul.

“This should have been a shut-and-closed case months ago,” Yvonne Taylor, cofounder of Seneca Lake Guardian, said. “We feel that the governor is selling out the Finger Lakes region on behalf of the oil and gas and the crypto industry. It is a complete betrayal and a slap in the face for the hardworking farmers and vineyard owners in the region.”

Hochul’s office did not respond to multiple requests for comment and the DEC declined to comment.

The state climate law, signed by former Gov. Andrew Cuomo in 2019, calls for a full energy transition to renewable power by 2040. It also requires greenhouse gas emissions to be reduced by 40% by the end of this decade and 85% by 2050, compared to 1990 levels.

The Finger Lakes cryptominers did not have a plan and did not show evidence of their intention to reduce emissions, according to the DEC review of the air permit application. Instead, the company argued the department did not have the authority to deny air permits to enforce the state climate law.

In November 2024, the Yates County Supreme Court ruled the DEC could deny air permits for operations that are not in compliance with the state’s climate law and that Greenidge’s activities were inconsistent with the law. The court gave Greenidge another opportunity to justify its operations by sending the case back to the agency.

The facility has operated continuously, solving complex algorithms that release new pieces of Bitcoin. The site was formerly a coal plant that was shut down in 2011. In 2014, Atlas Holdings LLC, a Connecticut-based investment company, bought the decommissioned facility and invested $100 million in converting it to natural gas, roughly equal to the value of the Bitcoin it mines in a single year.

At full capacity, the facility can power up to 75,000 homes in New York, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. There are only about 300 residents in Dresden, the town where the power plant is located.

According to the DEC, from 2017 to 2019, the plant’s annual carbon emissions were about 160,000 metric tons. In its first year of cryptomining in 2020, emissions increased to more than 400,000 metric tons. In the second year, emissions jumped again — by more than 20%, totaling more than 500,000 metric tons of greenhouse gases released into the air.

Last year, officials said the plant operated for more than 350 days, mainly to power its energy-intensive cryptomining operations. Before cryptomining, the plant operated for less than 50 days out of the year.

Residents say the noise from the power plant on the banks of Seneca Lake is unceasing and pervasive. They say they’ve experienced worsening algal blooms on the lake each year — harmful blankets of algae that can be exacerbated by the nitrogen oxides that natural gas facilities produce. They also take in large amounts of water from Seneca Lake to cool and then discharge heated water, which can contribute to excess algae and harm local wildlife populations. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the greenish laketop scum can contaminate drinking water, kill animals and make humans sick through ingestion, inhalation and skin contact.

Greenidge is not the Empire State’s only cryptominer. In North Tonawanda, near Hochul’s hometown, Digihost is operating a server farm to mine virtual currency. The situation is similar to the Greenidge case: The facility is operating on a permit that expired about four years ago. The DEC has yet to release the review for the draft air permit for public comment.

Similar operations have been emerging throughout the United States. Aside from cryptocurrency, artificial intelligence technology requires massive amounts of electricity and cooling capacity for server farms.

“This facility is kind of the canary in the bitcoin mine,” Aliperti, the vineyard owner, said. “If New York state can't get their arms around this and can't tamp this down, it's only going to encourage other power plants, other peaker plants to fire back up.”

Correction: This story's headline has been updated to clarify the gas plant's permit status.

Judge says upstate NY bitcoin mine can continue to operate despite climate concerns Crypto company slammed for pollution sues to keep mining bitcoin at NY power plant