Ten Moments In NYC LGBTQ Activist History You Need To Know In Addition To Stonewall

June 28, 2019, 11 a.m.

Occupations, zaps, and a City Hall climb are all part of queer New Yorkers' activist legacy.

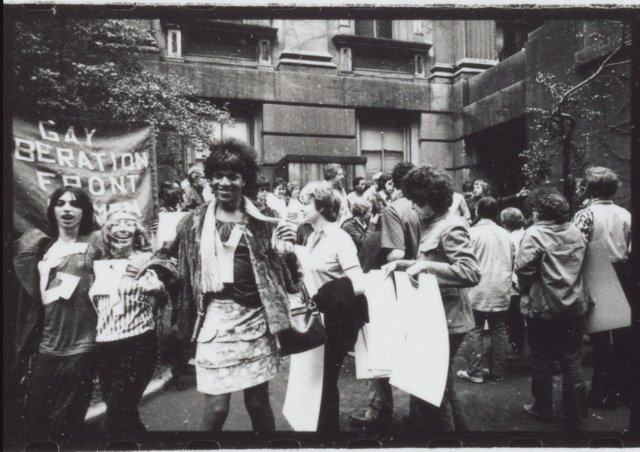

STAR co-founder Marsha Johnson at a Gay Liberation Front demonstration at City Hall, New York, in 1973

As we mark the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising today, public and private entities in New York are out in full force to celebrate the singular riot that sparked a transformation in LGBTQ activism across the country. Roosevelt Island’s Four Freedoms State Park has painted its steps with the colors of the Pride rainbow flag, and Tinder unveiled a 30-foot rainbow slide in Flatiron Plaza to encourage riders to “slide” into the DMs of senators to support the Equality Act.

But the buzz about the gay rights movement’s formative moment—as welcome as it may be—tends to overshadow a rich history of queer activism in the city. In the spirit of Pride, here are just a few lesser-known but also important protests that followed in the wake of the Stonewall Uprising.

August 4th, 1969: Kew Gardens Tree Protest

In early July 1969, just after the riots in Greenwich Village, the New York Times reported that trees in a Kew Gardens park frequented by gay men had been cut down by vigilante residents who were “concerned for the safety of the women and children,” seemingly with the consent of the NYPD. Despite pressure from the ACLU and the New York City Parks Commissioner, public reaction was muted; an assistant to the mayor suggested the parks department merely plant some grass where the trees had been felled.

The Mattachine Society, one of the nation’s first gay rights organizations, set up a fund to plant new trees and held a demonstration in the park along with the newly formed Gay Liberation Front. Attendees sported lavender armbands, and Stonewall veteran Martha Shelley staged a satirical play about three fictional Kew Gardens men repressing their sexuality. Marc Stein notes in The Stonewall Riots: A Documented History that activists purposefully planned the park protest to “let the women and children see the ‘menaces’ their husbands were protecting them from and to show that homosexuals intend to go anywhere they choose.”

September 20th-25th, 1970: Occupation of Weinstein Hall

Members of NYU’s Gay Student Liberation group and other queer activists occupied the sub-basement of Weinstein Hall for nearly a week in response to the school’s refusal to load out the space for such queer community events as fundraising dances and meetings. They stayed for almost a week, eventually radicalizing the initially wide-eyed NYU freshmen. (One student reportedly asked protester Karla Jay if they “were really revolutionaries or part of a street theater group.”) By the end of the fourth day of the occupation, straight NYU students had drafted a letter of support for the protesters.

NYU called the Tactical Police Force to evict the activists, at which point they demonstrated on the building’s steps until the evening. When everyone else retreated to their dorm rooms or homes, trans rights activist Sylvia Rivera and others marched to Sheridan Square. The incident would lead Rivera and Marsha Johnson to form Street Transvestites for Gay Power (later renamed Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, or STAR), a group that would confront homelessness, police harassment, and incarceration. “You people run if you want to, but we're tired of running,” their initial leaflet mocked. “We intend to fight for our rights until we get them."

May 1st, 1970: Lavender Menace Takes Over Second Congress to Unite Women

In early gay liberation movements, attempts to create lesbian-focused events were seen as divisive. Meanwhile, Betty Friedan had decried lesbians as the “lavender menace” in a 1969 NOW meeting, and had established a reputation for severing ties with lesbians and lesbian interest groups.

In response, a group called Lavender Menace presented their manifesto (“The Woman-Identified Woman”) at the Second Congress to Unite Women by staging a takeover. As the first speaker took the stage, two members cut the lights and mic. When the lights turned back on, the auditorium of IS 70 was filled with women in lavender t-shirts and holding signs with such slogans as “Women’s Liberation is a Lesbian Plot.” The demonstrators encouraged women in the audience to join them, and had some of their own members planted in the audience to encourage participation. One member, Karla Jay, stood up to join them, ripping open her shirt to reveal a matching Lavender Menace shirt. She sent the room into laughter when, after another woman volunteered to join them, she peeled off her shirt to reveal yet another Lavender Menace shirt.

The protesters handed out flyers and took the stage to discuss lesbian issues. The following year, NOW would adopt a resolution recognizing lesbian concerns as feminist ones; eventually, Lavender Menace would rename itself Radicalesbians. “The Woman-Identified Woman” would become an influential text in lesbian feminist history, and the group’s organizing led to a new focus on lesbian issues and the formation of more radical lesbian separatist groups like The Furies.

April 30th, 1973: Scaling City Hall

By 1973, legislation preventing discrimination based on sexual orientation had been debated at City Hall for three years. Discussion was fraught, with STAR battling for trans protections among gay activists and the straight city council. By the time of the third vote for the legislation, Intro 475, activists were convinced victory was certain. When the bill failed to pass the City Council’s General Welfare Committee by one vote, though, several days of protest followed.

During one demonstration, Sylvia Rivera gained particular notoriety for the moment she climbed City Hall. According to gay rights historian Stephan Cohen, she kicked off her heels, and in polyester bell bottoms, climbed up to a window, which was locked. Instead of climbing down, she continued to take sips of a drink as cops shouted, “Sylvia, if you jump, we won’t take you to jail.” Sylvia was arrested, along with some other protesters who had been disruptive in the chambers.

The City Council would not finally pass a gay rights bill until 1987—and then, without language protecting trans people. Rivera’s renewed activism at the end of her life helped force trans stories into the mainstream, but a trans rights law wouldn’t be established until 2009 under Gov. David Paterson.

Last month, First Lady Chirlane McCray announced plans for a new monument honoring Johnson and Rivera in Greenwich Village.

December 11th, 1973: Walter Cronkite Zap

Philadelphia Gay News founder Mark Segal, then a member of the direct action gay rights group Gay Raiders, snuck into the CBS Evening News studio by claiming he was a student journalist. Sixty million Americans were tuned in to watch Walter Cronkite deliver the day’s news, but fourteen minutes in, they instead saw Segal, waving a yellow cardboard sign that read “Gays Protest CBS Prejudice.”

Segal was protesting the lack of fair coverage gay news received at CBS—the network hadn’t covered gay rights bills being passed in cities all over the country, nor had it ever covered Pride. Segal was ultimately able to appeal directly to a receptive Cronkite, who challenged CBS executives and began running a gay rights segment on his broadcast. These televised confrontations would prove a popular activist strategy: Lesbian Feminist Liberation appeared on an episode of the Dick Cavett Show to protest an anti-feminist author in 1974, and ACT UP disrupted a CBS Evening News broadcast in 1991.

October 15th, 1982: Blues Bar Protests

Amid Ed Koch’s mission to “clean up” Times Square, the NYPD began raiding bars in the area, including Blues Bar—one of the few gay establishments that wasn’t mafia-owned and didn’t force black patrons to produce three forms of ID. During the first raid, police lined up the largely Black and Latino patrons to beat them, shout racist and homophobic slurs, and threaten them with guns. Thirty-five people were sent to the hospital.

Despite taking place across from the New York Times building, the raid received little coverage from mainstream media. After a second raid that met similar silence, over a thousand people from the black LGBT community and their allies gathered at Times Square, chanting “Hands off Blues!” and “Hey hey, ho ho, police brutality has got to go!” Groups like Black and White Men Together, Dykes Against Racism Everywhere, Salsa Soul Sisters, and El Comité Homosexual Latinamericano were present and would later form the Coalition Against Police Repression. The demonstration forced the Times to run a small article acknowledging police brutality against Black and Latino gay men.

December 10th, 1989: Stop The Church Protest

In the midst of the AIDS crisis, Cardinal John O’Connor railed against homosexuality and AIDS education, which he claimed promoted acts that "were not in keeping with the teachings of the Catholic Church." Forty-five hundred members of ACT UP and the Women’s Health Action Mobilization (WHAM!) protested outside the church, some dressed as clowns and priests. Dozens of protesters stormed mass itself, laying down in aisles or chaining themselves to the church pews. One protester crumbled a communion wafer and threw it on the floor. ACT UP insisted it was the personal protest of one Catholic demonstrator, but the act ignited the ire of politicians, the media, and other gay rights organizations. Ultimately 111 protesters were arrested, some of whom had to be carried out on stretchers. Some ACT UP members say the controversial action helped deconstruct the notion that the Catholic Church was untouchable and beyond questioning.

October 31st, 1992: Hattie Mae Cohens and Brian Mock Memorial

The Lesbian Avengers’ initial protests targeted a Queens school board’s reluctance to include a diverse curriculum, but it was their Halloween 1992 action two slain queer people that cemented their reputation. Hattie Mae Cohens was a black lesbian woman living in Oregon who died along with her white gay roommate, Brian Mock, when their apartment was firebombed by white supremacists amid debate about an anti-gay amendment being voted on in Oregon. To commemorate their deaths and protest the amendment, the Lesbian Avengers marched with the Anti-Violence Project and built a shrine to the pair. Lesbian Avenger Lysander Puccio concluded a speech to mourners by chanting, “The fire will not consume us. We take it and make it our own,” as each Avenger ate fire. The vigil continued through election day, and fire eating would become the groups signature move. Though short-lived, the group created the first Dyke Marches in Washington, D.C., and New York City.

April 4th, 2011: Drag Queen Wedding/March

In 2011, Andrew Cuomo was serving his first term as governor and had made gay marriage a focal point of his campaign. But progress was slow and some groups pushed to include marriage equality in his executive budget. The group Drag Queen Weddings for Equality staged a marriage ceremony in Grand Central station’s main hall. The NYPD interceded before vows could be completed, but another activist was able to attach balloons to a banner advocating for marriage equality, where it floated above the station’s commuters. Along with Queer Rising, the protesters then marched to Cuomo’s office and stopped traffic by unfurling a banner across Third Avenue. A few months later, Cuomo would sign New York State’s marriage equality law.

February 25th, 2019: Sex Work is Work Launch

Over 100 sex workers gathered with politicians to announce a new coalition known as Decrim NY, hoping to end the criminalization and stigma of sex work. Cecilia Gentili, on the steering committee for Decrim NY, was among the trans women who spoke about being targeted by police under a loitering law that had been used to harass trans women of color. “I found myself in Rikers Island for doing sex work. And right after Rikers, I was sent to immigrant [detention] with ICE,” said Gentili, an immigrant from Argentina, “This criminalization of sex work could have sent me to a country where I would have been killed right away.” Decrim NY has helped craft a bill that would repeal the loitering law.