NYC Mayor Adams has a mental health agenda. Will Albany play ball?

Dec. 1, 2022, 12:40 p.m.

State lawmakers have given a decidedly mixed response to Adams’ plan and proposals, with a handful fully embracing it while others expressed concern about civil rights.

New York City Mayor Eric Adams has a plan to remove what he calls “barriers” to providing proper care for those believed to be in the throes of a mental health crisis.

Now he just needs support from a group that has, at times, been loath to give it to him: Democratic lawmakers in Albany.

Adams’ directive to involuntarily remove more presumed mentally ill people from the city’s streets and subways and send them to hospitals for evaluation is based on a broad reading of existing state law — which is backed up by state guidance but will likely be challenged in court.

At the same time, Adams is pushing an 11-point legislative agenda that would, among other things, change state law to make clear his plan is legal and require mental health evaluators to consider a patient’s history when deciding whether to commit them. That would require passage by the Democrat-led Legislature, with which the mayor has had an up-and-down relationship during his first year in office.

“Our team has developed an 11-point legislative agenda to address those gaps, and getting it enacted would be a major priority for us in 2023,” Adams said on Tuesday when announcing his plan.

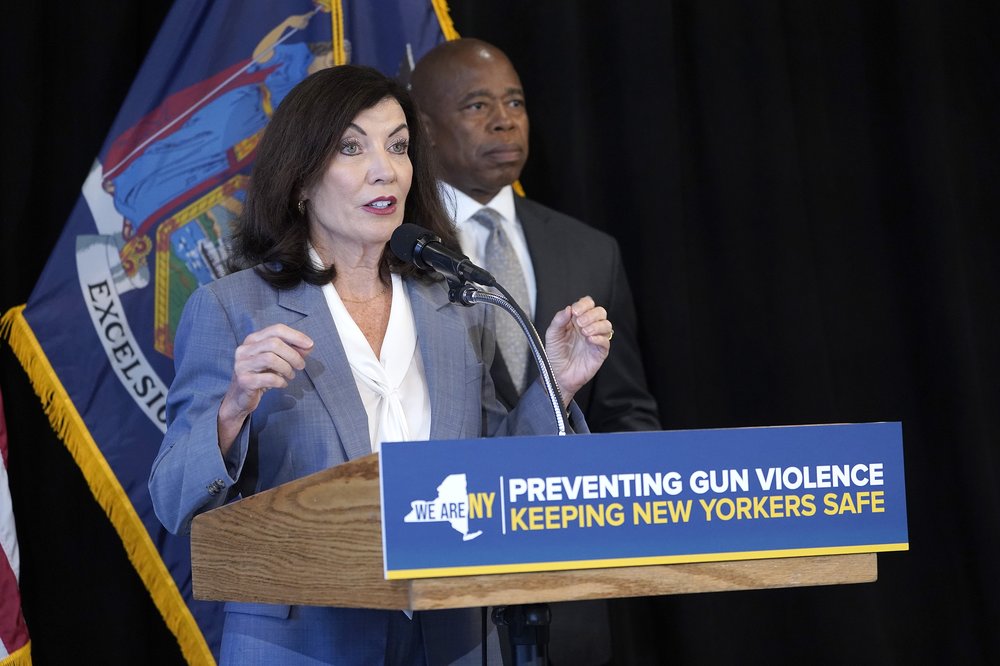

So far, state lawmakers have given a decidedly mixed response to Adams’ plan and proposals, with a handful fully embracing it and others expressing concern about civil rights. Among the three most powerful figures in Albany — Gov. Kathy Hochul, Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins and Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie — reaction has ranged from wait-and-see to tepid support.

“We understand the need to deal with the ongoing mental health crisis affecting so many New Yorkers,” said Mike Murphy, a spokesperson for Stewart-Cousins, a Democrat representing Yonkers. “We look forward to working with the [Adams] administration to address these issues next session.”

A spokesperson for Hochul, Hazel Crampton-Hays, said Adams’ plan “builds on our ongoing efforts together,” while Heastie’s spokesperson Michael Whyland said: “We would have to review any proposal with our members.”

Adams’ mixed Albany record

The mayor, a former state senator, has boasted of his ability to navigate Albany, which holds significant sway over what the city can and can’t do on its own. But his record of getting his legislative priorities passed was mixed during his first year in office.

The state Legislature granted some of his major requests, including the creation of a trust to fund public housing repairs and an expansion of the earned income tax credit. But lawmakers resisted his plea to grant judges the ability to consider a defendant’s “dangerousness” when setting bail, and also saddled him with a school class-size mandate he vehemently opposed.

Adams’ 11 proposals focus on issues where someone is experiencing what appears to be severe mental illness. If approved, the measures would make clear that someone can be involuntarily transported to a hospital if they are “unable to meet their basic survival needs” of food, shelter and/or medical care — which, Adams claims, is already allowed by current law, though not explicitly mentioned. His proposal would install his interpretation into the law, eliminating ambiguity and making it less susceptible to potential court challenges.

The mayor’s proposals, which would have to be introduced by lawmakers, would also require hospitals to share more information with local community providers and city officials in certain situations and expand the list of professionals that can order a hospital evaluation.

Updating Kendra’s Law

Several of the remaining points focus on Kendra’s Law, which allows court-ordered outpatient treatment for someone deemed to be a danger to themselves or others. Among other changes, Adams wants the state to mandate at least a year of treatment in most cases and allow psychiatrists to testify by video.

During his speech Tuesday laying out his plan, Adams said it addresses “long-standing gaps” in state law. He was flanked by at least four Democratic state lawmakers: state Sen. Simcha Felder of Brooklyn, Assemblymember Eddie Gibbs of Manhattan, and Assemblymembers Ron Kim and Jenifer Rajkumar of Queens.

Assemblymember Jo Anne Simon, a Democrat representing Brooklyn, said she believes Adams’ administration is trying to do something to help people, but worries the mayor’s interpretation of the law is not a “constructive approach.”

Current law allows involuntary commitment if someone “appears to be mentally ill” and is “conducting himself or herself in a manner which is likely to result in serious harm to the person or others." Under Adams’ interpretation — based on February guidance issued by the state Office of Mental Health — that can include when someone can’t “meet basic living needs,” even if their evaluators didn’t observe a dangerous act.

Simon says that definition is too broad for her liking, and she would have concerns about cementing it in state law.

They're sort of playing a little fast and loose with the standard. It's kind of trying to change the standard, but that standard is constitutional.

Assemblymember Jo Anne Simon

“For there to be an involuntary commitment order or request, you have to be a danger to yourself or others, right? That's the standard,” Simon said Wednesday after a mental health hearing in Albany. “The problem I see with this is they're sort of playing a little fast and loose with the standard. It's kind of trying to change the standard, but that standard is constitutional.”

Simon and Brooklyn state Sen. Zellnor Myrie have sponsored a bill meant to better connect people to treatment if they appear to be mentally ill when they interact with the justice system. The Assembly approved it in June, but the Senate never took it up.

It’s one of at least two bills favored by public defender organizations. The other is a measure sponsored by state Sen. Jessica Ramos, a Queens Democrat, called the Treatment Not Jails Act, which would create a voluntary mental health and substance use diversion program that would be available through the courts without having to plead guilty to a crime..

Ramos said she has several concerns with Adams’ plan, including a lack of apparent training for emergency responders who will be tasked with requesting transport for the presumed mentally ill.

“I think it's very concerning that most of the members of the NYPD, FDNY, EMS and all the other agencies that will be deployed for this purpose haven't actually received the training to do so,” she said. “And to then put us in a position where a person's self-determination can be taken away — well, then, obviously it’s a big concern.”

Mental health advocates weigh in

Harvey Rosenthal, CEO of the New York Association of Psychiatric Rehabilitation Services and a longtime advocate for community-based care, called Adams’ proposals a “flawed approach.” Rosenthal, a frequent presence in the state Capitol, said he intends to push back against anything that “encourages more coercion.”

“It's obviously a violation of rights and ethical practice in my mind, but it really is a terrible substitute for a functioning mental health system that is accountable to give people their right to the best kind of care,” he said. “To instead force them into services that have already failed them for six months or a year — we want a system that engages people.”

Rosenthal, who opposed a five-year extension of Kendra’s Law that lawmakers approved in their session earlier this year, called Adams’ involuntary commitment plan “another example of system failure.”

“We're going backwards because we can't figure out how to serve people in the community so we're going to hospitalize them in institutions again,” Rosenthal said. “So we'll be fighting that, yes. Last [session] was horrible and this year stands to be much worse."

We need [psychiatric] beds ... There's no getting around that. We need beds.

Mayor Eric Adams

One area where Adams is likely to be met with broad consensus is on the need for additional psychiatric beds at hospitals.

About 1,000 such beds were converted for other needs during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Earlier this year, Hochul and state lawmakers allocated more than $27 million toward bringing them back — but only 200 or so have been brought back on line since then, the Gotham Gazette reported this week. More than 400 remain unavailable in the city.

“We need beds,” Adams said Tuesday. “There's no getting around that. We need beds.”

Several lawmakers echoed the call for additional psych beds, including Ramos and Assembly Mental Health Committee Chair Aileen Gunther, an Orange County Democrat.

“I'm pleading to make sure that we have beds, that people that are in a crisis can go into a hospital and be treated,” she said.

State lawmakers are scheduled to return to the Capitol in January. Their annual session is scheduled to run until June.

Mayor Adams directs NYPD, first responders to involuntarily take mentally ill to hospitals NYPD already gets hundreds of annual abuse complaints for forcing people to hospitals