NYC is flush with opioid settlement money yet prevention centers are still scrambling for funds

May 23, 2022, 12:13 p.m.

NYC officials have millions of dollars from legal settlements that they can immediately spend to fight the opioid crisis. But they have not revealed any detailed plans, even as local nonprofits struggle for funding.

Since OnPoint NYC started letting people use drugs under staff supervision at its sites in Harlem and Washington Heights a little over five months ago, the centers have intervened in about 300 potentially life-threatening overdoses, according to the nonprofit.

Only five resulted in the costly ambulance visits that would typically arrive for an overdose on the street and only one person went to the hospital, the organization said.

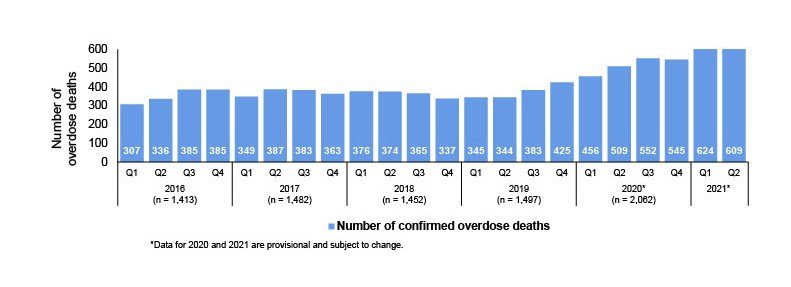

At a time when overdose deaths in both New York City and the U.S. are at all-time highs, OnPoint NYC is looking to extend its hours to operate around the clock, while other local nonprofits are working to open similar facilities. But all are scrambling to raise money from private donors to do so, since they aren’t permitted to directly use public funds to operate overdose prevention centers, also referred to as supervised injection facilities.

Leaders of these nonprofits, which include OnPoint NYC, Vocal-NY and Housing Works, say they would be able to use public dollars for these services if the federal government altered its policy on the facilities, which are currently allowed in New York City but still illegal under federal law. State officials could also authorize overdose prevention centers, either through a bill that’s pending in Albany or regulations from the state Department of Health.

But the Biden administration has punted on the issue multiple times. State legislators are split on the matter and Gov. Kathy Hochul has yet to offer her support.

Meanwhile, New York City is being flooded with millions of dollars to fight the opioid crisis from settlements that the state Attorney General recently reached with pharmaceutical companies. The five boroughs are currently due $256 million in all. The city has already received at least $11.5 million of the $89 million that’s expected this year alone.

Clients use drugs at supervised booths in OnPoint NYC's overdose prevention center in Harlem. Mirrors make it easier for staff to keep an eye on the clients in case they need overdose treatment.

City officials have sole discretion over how to spend this money but have not revealed who will be involved in the decision-making process or how long it will take. During public appearances and in an email to Gothamist in April, they have responded to questions about how the money will be allocated by pointing to a state committee — called the Opioid Settlement Advisory Board — that has yet to meet.

Yet, all of the settlement money State Attorney General Letitia James has announced for New York City so far will arrive through a third-party administrator, meaning the state’s advisory board will not be involved in deciding how it’s spent, Evan Frost, a spokesperson for the state Office of Addiction Services and Supports (OASAS), confirmed. That board is designed to make recommendations regarding a separate pot of settlement money that will be allocated by the state.

Asked Friday whether any of the settlement funds the city is receiving would go to overdose prevention centers, Kate Smart, a City Hall spokesperson said, “We are in the process of evaluating how to best invest this money to save lives and build a healthier city.”

Who’s “we”? She would not say.

We are in the process of evaluating how to best invest this money to save lives and build a healthier city.

Kate Smart, City Hall spokesperson

Sam Rivera, executive director of OnPoint NYC, said he had faith that some of the settlement money would flow to overdose prevention centers.

“I believe we're going to get it and if we don't get any, you will be hearing a lot from me,” he said. “That's for sure.”

New York City took the risk of becoming the first jurisdiction in the country to authorize these controversial facilities under former Mayor Bill de Blasio, and Mayor Eric Adams has said he wants to expand them.

“Every single day, overdose prevention centers are giving people in pain another chance,” Adams tweeted Wednesday. “It's time to go further — this administration fully supports making overdose prevention centers accessible 24 hours a day. A crisis doesn't wait, and neither should we.”

But the Adams administration is currently withholding funds for overdose prevention centers until there’s a change in state or federal policy, according to Rivera and officials at Vocal-NY and Housing Works. Rivera said he has “partners” at both the city and state health departments who “support us 100%,” but who have indicated that their hands are tied when it comes to funding — for now.

Neither city nor state officials would confirm that government funding would become available if a policy change occurred.

Frost from OASAS simply said, “New York State does not have any involvement in or provide any funding for overdose prevention centers.”

Where does Biden stand?

The U.S. Department of Justice under former President Donald Trump said overdose prevention centers violate the Crackhouse Statute — a measure that President Joe Biden authored in the 1980s when he was a U.S. Senator. The statute made it illegal for anyone to knowingly provide a space for people to use illicit drugs.

The Trump administration sued Safehouse, a nonprofit in Philadelphia, to prevent it from opening an overdose prevention center in 2019. After a federal appeals court ruled against Safehouse last year, the nonprofit reopened the case at the district level with new arguments. Its reported goal was to force the Biden administration — which has publicly indicated it might be open to overdose prevention centers — to respond and take a stance on the issue. But the deadline to do so has been extended multiple times.

Most recently, the Justice Department got the date pushed from May 9th to June 23rd. Two days after the missed deadline, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released data showing that more than 100,000 Americans had died of a drug overdose in 2021 — a new record for a single year.

Still, Safehouse Vice President Ronda Goldfein said in February that her organization had agreed to previous delays “because of productive conversations” with the federal government.

“We believe a settlement would clear a path for these services to be offered across the U.S.,” Safehouse tweeted on May 9th.

Charles King, president and CEO of the nonprofit Housing Works, which is trying to open overdose prevention centers in Manhattan, said he anticipated that a settlement would be reached in the case and the U.S. Department of Justice would issue guidance “that will allow states to experiment with overdose prevention centers.”

The Department of Justice did not respond to a request for comment on whether it was developing such guidance.

In the meantime, the lack of public funding could force Housing Works to open just one overdose prevention center to start, rather than the two that were planned, King told Gothamist.

The harm reduction and advocacy group Vocal-NY is waiting to open its overdose prevention center until it moves into a new building in Brooklyn. At the same time, it’s working to raise funds to pay for “everything that happens in that room” where the supervised drug use will take place, said Jasmine Budnella, director of drug policy, organizing and campaigns at Vocal-NY.

Rivera said that if his two overdose prevention centers were open all the time, they would cost close to $2 million per year to operate. But he argued that by reducing costs for emergency services and hospital stays, “We’re saving the city lots and lots of money.”

In its response to the preliminary budget Adams issued in February, the City Council called for an investment of $10 million to create 24-hour overdose prevention centers in every borough — whether through public or private funds.

Getting state support

Gov. Hochul could allow State Health Commissioner Dr. Mary Bassett to issue regulations authorizing overdose prevention centers without involving the state legislature.

Bassett herself has been a vocal supporter of the facilities, as is Dr. Chinazo Cunningham, the commissioner for OASAS. But Bassett told the State Senate Health Committee in January, “The governor has said quite clearly that she’s not there yet.”

It’s unclear whether Hochul has changed her position since then. Her office did not respond to a request for comment.

Still, advocates are hopeful that the governor would sign legislation authorizing the centers if it passed. They are pushing a bill known as the Safer Consumption Services Act that would permit both the state health department and individual localities to approve new overdose prevention centers across New York.

The measure is starting to gain some momentum after years in limbo. State Assemblymember Linda Rosenthal first introduced the bill in 2017. It moved out of the Assembly Health Committee for the first time this month. But this recent push may not be enough to get it through before the legislative session ends on June 2nd.

The only way we're going to save people's lives and have a chance at giving them a path to a better life is to make sure they don't overdose and die.

Linda Rosenthal, New York Assemblymember

“Everyone is getting increasingly alarmed, as they should, by the overwhelming number of people succumbing to overdose,” Rosenthal said in an interview. “The only way we're going to save people's lives and have a chance at giving them a path to a better life is to make sure they don't overdose and die.”

Rosenthal said some legislators who previously told her overdose prevention centers wouldn’t fly with their constituents are now supporters.

But the bill still faces some opposition in both houses and has less support in the state Senate, where it has yet to advance.

Senate Minority Whip Patrick Gallivan, a Republican from Western New York who opposes overdose prevention centers, said advocates made a “compelling argument that they’re reducing harm to the individuals because they’re not dying.” But he said that must be weighed against potential downsides for the residents who live around these facilities, such as more trash and illegal activity on the streets.

Rivera of OnPoint NYC has argued that his centers help reduce public drug use, thereby also decreasing the presence of used needles and other drug paraphernalia in public spaces. But the activity in the centers does sometimes spill out into the neighborhood. For instance, when the center in Washington Heights closes for the night, clients sometimes migrate to a nearby subway station to use drugs, according to a recent story from The City. Rivera said that’s why his center should be open 24 hours.

Ann Marie Vazquez, a born-and-raised Harlem resident, said she also has seen more drug dealers in the area near the center on East 126th Street since OnPoint NYC began offering overdose prevention services there (both locations already operated syringe exchanges previously). She said it made the area feel more dangerous.

“I know they've sold drugs in front of that program for years, but it's never been this bad,” Vazquez said.

Some Harlem residents protested the centers when they first opened in December, saying they should be put in neighborhoods that are less saturated with other services for drug users.

The NYPD did not respond to a question Friday about whether there had been increases in drug sales or other illegal activity near the centers since they started offering overdose prevention services.

State Sen. Gustavo Rivera, the bill’s primary sponsor in the Senate, said he has been working to address some of his colleagues’ concerns.

“It is definitely a controversial measure and I understand the skepticism,” he said in an email. “Deeply held stigma takes a lot of work to undo, but it's worth it if we can save lives and prevent harm to more New Yorkers.”

Rosenthal said the goal of the Safer Consumption Services Act is to bring overdose prevention centers to other parts of the state.

But Rivera of OnPoint NYC is convinced it will do more than that.

“If it passes, we can receive funding from the state,” he said. “And they do want to fund us. They know it’s the right thing to do.”