New DOE Agreement With NYPD Attempts To Take School Security Past The 'Giuliani Days'

June 21, 2019, 2 p.m.

The Department of Education and the NYPD have updated school security policies, crafting a new official agreement for the first time since 1998.

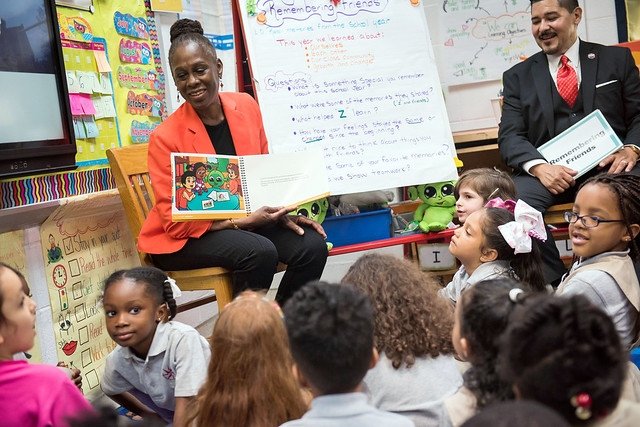

First Lady Chirlane McCray and Schools Chancellor Richard A. Carranza on Thursday.

The Department of Education and the NYPD have updated school security policies, crafting a new official agreement for the first time since 1998.

The Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) calls for fewer arrests for low level offenses, an increased emphasis on conflict resolution, and more social workers in the city schools. It says that in all but the most extreme cases, suspensions shouldn’t last more than 20 days, and students should generally not be arrested for infractions like graffiti, alcohol consumption and low-level marijuana possession.

The de Blasio Administration says the agreement is part of a broader effort to give students emotional support rather than punishment.

Officials announced the new MOU at a press conference on Thursday that also unveiled a partnership to advance “social-emotional learning” programs at elementary schools citywide and restorative justice training at middle schools. They said 85 social workers will be dispatched to schools to help students in crisis, part of a budget agreement brokered with the City Council that will add some 200 school social workers citywide.

“This is a moment where students are going to get the support they need to be their best selves,” Mayor Bill de Blasio said. “Teachers are going to get the tools they need to help a child, the whole child, when there’s a challenge or a problem.”

Students activists have demanded school security reform, calling for "counselors not cops" through the Black Lives Matter in schools movement, and emphasizing restorative justice as a key part of broader integration plans.

Rikya Kee, a high school senior who’s advocated for these changes with the Urban Youth Collaborative and Sistas and Brothas United, called the move a “step towards ending the school to prison pipeline.”

The police and education department have been working with advocates for many years, even decades, to craft the agreement.

“This is a huge, really, really important step,” said Johanna Miller, Director of the Education Policy Center at the New York Civil Liberties Union. “But it’s not everything.”

She and other had wanted to see more transparency around the use of metal detectors and stronger restrictions on the use of restraints.

“It’s a huge step forward for regulating police in schools,” she said, “but it doesn’t decrease the number of police in schools.”

The agreement states school personnel—not police—should be the first responders to non-criminal conduct by students, and police will consult educators more when responding to incidents.

NYPD Assistant Chief Ruben Beltran said officers in schools have already been doing that as part of a new warning card program. “We’ve given around 300 warning cards,” he said. “And before issuing warning cards, we discussed that with the administration in the schools, with the principals, about is this the best course of action, is there any past history...So we make that decision jointly together.”

The agreement also calls for more integration of police into school communities, by attending staff and PTO meetings, for example.

De Blasio and Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza said the agreement reflected a shift in values, akin to “neighborhood policing” on city streets.

“Skeptics said if you move away from punishment and focus on keeping kids in school while holding them accountable our schools will be less safe,” said Carranza. “I say that’s a false narrative."

The Department of Education’s statistics show black students are not only more likely to be suspended but often get harsher punishments. Officials say suspensions over 20 days are rare. Last year only 9 percent of suspensions were longer than 20 days last year, and 6 percent this year. But suspensions have also stretched as long as 180 days.

“We are long past the Rudy Giuliani days in New York City,” said Council Speaker Corey Johnson. “This is a new city with new values.”

First Lady Chirlane McCray said a new curriculum called Sanford Harmony would help teachers and students process emotions to help prevent conflicts from erupting in the first place.

“Maybe a fight with a friend left them angry. Maybe they are fearful that their family will be evicted from their home,” she said. “Without the skills and safe space to talk through how they’re feeling they might express their emotions by withdrawing…or drawing attention to themselves with disruptive behavior.

“The appropriate question to ask in these cases isn’t ‘What’s wrong with you? The question to ask is, ‘What happened to you? Why are you feeling this way?’”

McCray pointed to a pilot program at Meyer Levin Junior High School in East Flatbush, Brooklyn, where students have regular “town hall” meetings to air their experiences and support each other.

“When one student shared her worries about the results of her grandmother’s custody hearing, there was no jeering on taunting,” she said. “Her classmates responded with empathy and encouragement.”

Jessica Gould is a reporter in the newsroom at WNYC. You can follow her on Twitter at @ByJessicaGould.