Is this Queens plaque at the ‘center’ of NYC or just the center of a decades-old mystery?

Dec. 24, 2024, 12:01 p.m.

A plaque in Woodside, Queens claims to mark the geographic center of NYC. But geographers say it’s not. So who put it there? And why?

At first glance, there’s nothing particularly special about the intersection of Queens Boulevard and 58th Street in Woodside.

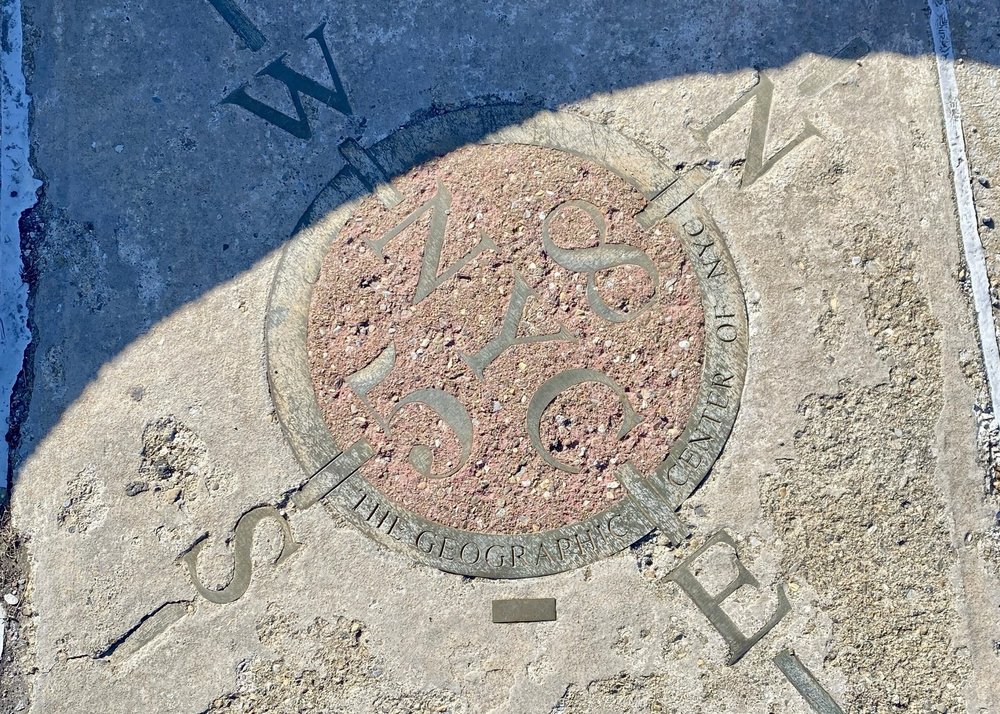

But embedded in a traffic median near the northeast corner is an enduring mystery: a modest plaque resembling a compass rose that claims to be “the geographic center of NYC.”

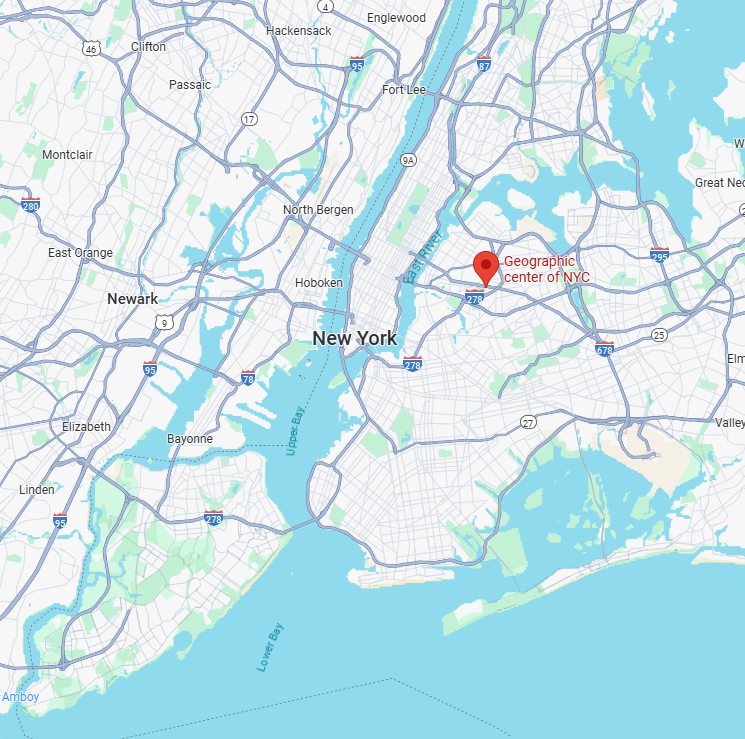

According to geographers and city officials, the claim is false. New York City’s geographic center is more or less accepted as being in Bushwick, Brooklyn — on Broadway between Lawton and Dodworth streets — a little more than 4 miles southwest of the plaque.

I was born and raised in Queens, not far from Woodside. So when I became aware of this mystery, I was determined to find out who put this plaque there and why. A weekslong inquiry into the marker’s provenance and the reasons behind its installation turned up more questions than answers.

My investigation began with contacting representatives of various city agencies who would know about any official city markers. It soon became apparent that they knew as much as I did.

Courtney Clark Metakis, the spokesperson for the city’s Landmark Preservation Commission, said the marker is “very interesting” but wasn’t sanctioned by her agency.

“[It’s] not one of LPC’s markers, nor is it under LPC’s jurisdiction (it’s not located on a landmark site or in a historic district),” she said in an email. “I don’t have any information about it.”

Parks department spokesperson Judd Faulkner told me that “this is not NYC Parks property and we have no records of the marker.”

Joe Marvilli, a spokesperson for the Department of City Planning, said “DCP does not have any information about the origins of this plaque.”

Michael Scholl, a spokesperson for the Queens borough president, directed my inquiry to the city’s Department of Transportation. But DOT spokesperson Mona Bruno said her agency didn’t install the plaque, either.

“It is by far one of the strangest anomalies in Queens,” said Jason Antos, head of the Queens Historical Society.

Enter the bounding box

Could the marker’s placement have been a simple oversight or an honest mistake? After all, not everyone necessarily agrees on where New York City’s center is.

A 2005 New York Times article claims it’s on Stockholm Street between Wyckoff and St. Nicholas avenues, about a mile northeast of the "true" city center. Meanwhile, a 2006 Gothamist article puts the geographic center around the intersection of Broadway and Chambers Street. And New York City’s “mile zero” — the place from which all official highway distances from the city are measured — is traditionally located at Columbus Circle.

So how might one even go about determining where a city’s geographic center is? I contacted Sean Ahearn, a Hunter College geography professor who directs the school’s Center for Advanced Research of Spatial Information. He explained that we’d begin with a polygon containing the five boroughs — what’s known in geography as a bounding box.

“The absolute simplest way is to take the bounding box of the city of New York and to take the maximum X, maximum Y, minimum X, minimum Y,” Ahearn said, referring to coordinates within the polygon. “And then you know, subtract those to get the midpoint, and that would give you a centroid for the city.”

Could the small islets and rocky outcroppings in New York City’s waters affect that calculation at all? Not really, said Ahearn.

“Anything that is designated as New York City would be included in that polygon for sure. So it would hug the shoreline, but if there was an island out there, you’d have to move out to [account] for that as well,” he said. “How exactly you do that is gonna make some difference, but not a crazy amount of difference.”

With no help from City Hall or science, I considered another possibility: My Queens neighbors and I were being punked by a plaque.

I reached out to Joseph Reginella, a Staten Island-based sculptor known for humorous works depicting fictitious New York City figures and events. Surely he would have heard if one of his compatriots had installed a prank plaque.

“I’d like to believe that maybe there’s two scenarios: That the city commissioned somebody to do it and then it turned out that they were totally wrong and they left it,” Reginella said in an interview. “Or somebody put it there maybe as a joke and a prank and it’s just been sitting there for years and nobody’s realized it until now.”

Even for Reginella, the sheer audacity of such a stunt was noteworthy.

“That’s a very strange prank to pull, because I mean you really have to play the waiting game on that,” he said. “And I mean, that thing looks like it’s been sitting there for a long time, you know?”

The marker bears no information about who installed it or when. I was able to verify via Google Street View that it has been in place since at least 2007. A Flickr photo of the marker dating to July of that year shows that it once had shimmering brass or bronze trim, which has since grown dull and weathered. But there wasn’t much else to go off of, and the trail went cold.

After several dead-end leads, I got a break in the case.

In my search for answers, I made a post in We Are Woodside, a neighborhood Facebook group, and it gained some traction.

Dozens of commenters speculated about the mysterious marker’s origins. Some theorized that it had to do with Robert Moses’ vision of a greater New York that also included Long Island. Others said they were taught that the city’s true center is under Calvary Cemetery, located diagonally from the marker across Queens Boulevard. But many had never questioned the marker or paid it much mind, if they’d even noticed it at all.

“Woodside has always been the heart of New York City to me,” said Eric Gioia, the area’s city councilmember from 2002 to 2009. “Whether or not it’s the exact geographic center, I don’t know, but it remains the heart.”

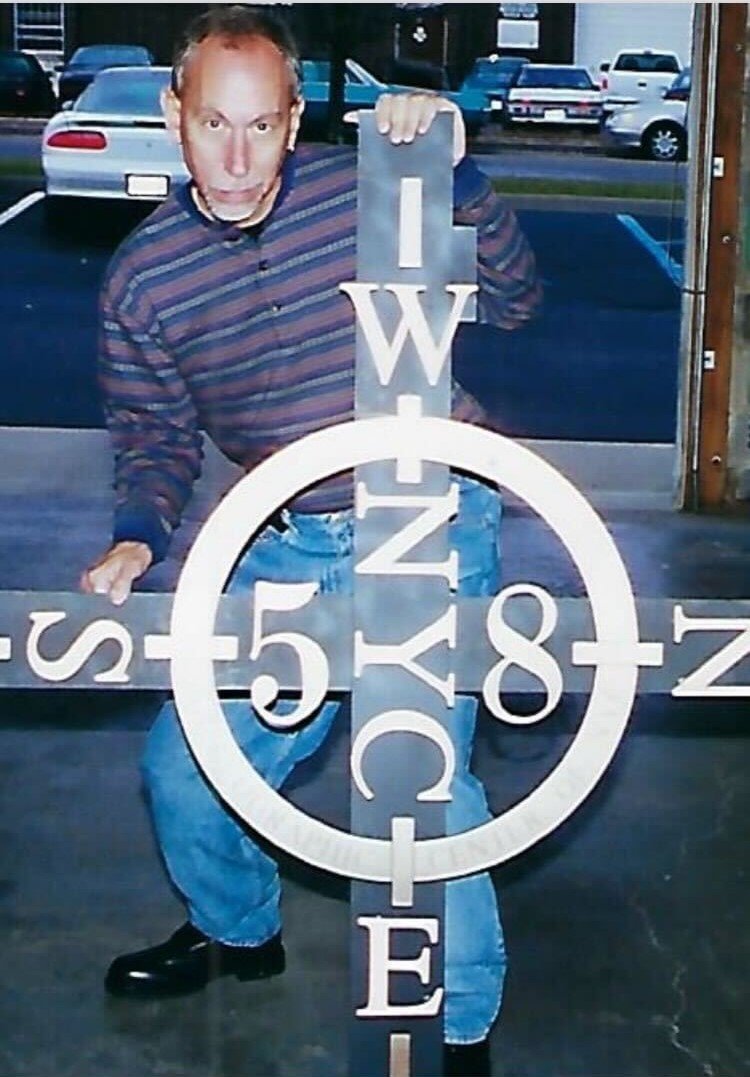

One particular comment stood out. It contained a link to a recent post by John Cola, who said the marker was assembled at the machine shop of his father-in-law, Henry Thode. Cola said the shop got the job from Wemco, a small, family-owned metal caster based in Long Island. Cola said he’s been independently investigating the marker since he first saw a video about it years ago and found out his in-laws played a part in its creation.

“I told my wife, I said, ‘Hey, look at this, this is cool,’” Cola told me. “She looked at it, and the second she looked at it, she goes, ‘My father built that.’”

In his post, Cola said his father-in-law’s shop “was in Farmingdale, he got the job from a company in Bohemia that got the parts from a foundry in Pennsylvania.”

That post included a photo of the marker being assembled on the floor of what appears to be a machine shop. He later sent more photos of a worker holding the marker. Cola estimated the photos dated back to around 1994 because a brand new Chevrolet Camaro from that year is visible in the background of one of the images.

But Cola said his contact at Wemco couldn’t remember who commissioned the marker, which foundry its parts came from, or who actually installed it. He said he was told the job was so long ago, records don’t exist anymore. He put me in touch with his brother-in-law John Thode, whom he described as “the last guy to touch it before it was dropped into Queens Boulevard.”

“I made the skeleton, if you will, attached all the letters, you know, made sure they were lined up,” Thode said. “And then the whole apparatus was assembled then I delivered it and whoever installed it, installed it.”

Thode said he assembled it sometime around 1994, but doesn’t remember who commissioned it or to whom it was delivered.

The king of the compass rose

After weeks of digging, I heard from a high-level source who posited the most likely theory to date.

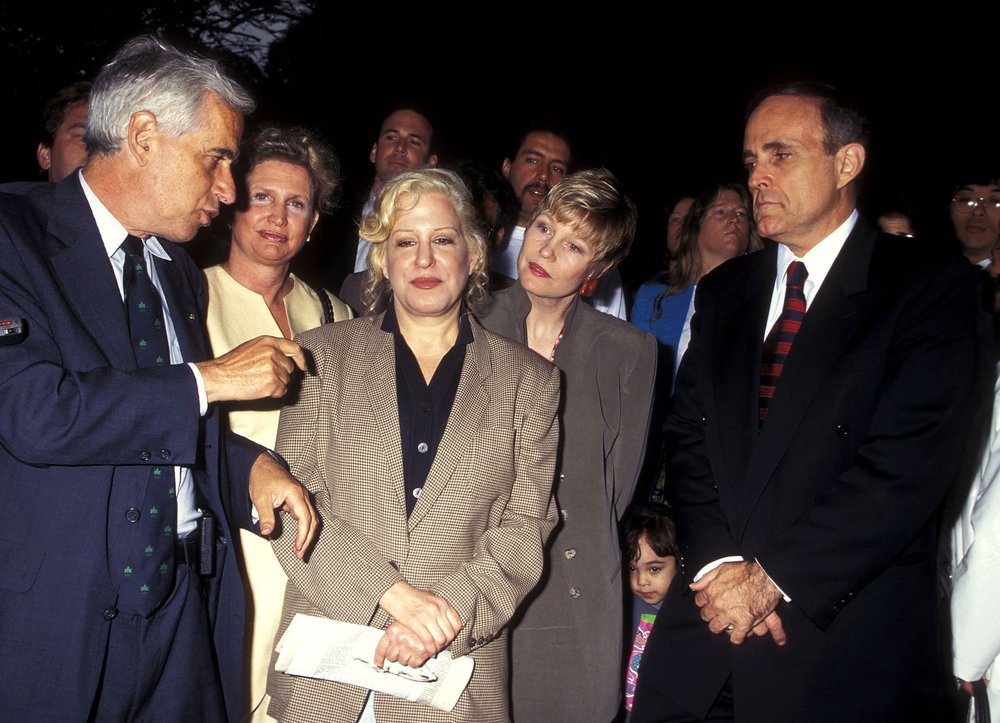

“I can’t confirm or deny, but certainly a case could be made that this has the fingerprints of Henry Stern on it,” said former Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe, naming his immediate predecessor, Stern, as a possible mastermind.

"Any place you find a compass rosette, it’s because Henry Stern said there must be a compass rosette."

Brooklyn Botanic Garden President Adrian Benepe, a former parks commissioner

Stern served as the city’s parks commissioner under Mayors Ed Koch and Rudy Giuliani — from 1983-1990 and 1994-2000. Benepe, who now runs the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, said Stern was known for his eccentric humor — his quirks included an obsession with numbers and how they fit together. Add that to an intimate knowledge of the city's geography and a portrait of the suspect begins to appear.

“He was such an autodidact and such a good mathematician, he might’ve made his own computations as to what the geographical center might be,” Benepe said.

He told me the malls on many New York City boulevards are maintained by the parks department, but are generally under the jurisdiction of the Department of Transportation. It started to become clear why the current parks department had no records: Benepe said putting a mysterious plaque on the median “might have been a guerrilla move by [Stern] to try to acquire those malls and green them up.”

“He’d go onto pieces of property under the jurisdiction of other agencies, particularly DOT, and kind of claim them without asking permission,” Benepe continued. “And put a park flag or park leaf on it, particularly things like malls in the middle of boulevards, especially if they’re landscaped.”

Stern was also fond of issuing decrees about parks and playgrounds. He required them to include common elements, such as flagpoles, animal art or equipment, and, of course, compass roses.

“Any place you find a compass rosette, it’s because Henry Stern said there must be a compass rosette so people know what their location is geographically,” Benepe said.

Stern died in 2019 at the age of 83. In an obituary, the New York Times wrote that he'd "presided over New York City’s emerald empire for 15 years as commissioner ... surpassing all but the Napoleonic Robert Moses in tenure and enhancements to the city’s greenswards and playgrounds."

And for now, that's where my investigation ends. Thode’s creation and Stern's potential mischief still sit at the center of one of New York City’s oddest mysteries.

“To me, it was just a standard job, I do stuff like this all the time,” Thode told me. "There’s nothing outstanding about it. I’ve never even seen it."

He added, “I don’t think I’m gonna make the trip, to be honest.”

Editor's note: This remains an active Gothamist investigation. Anyone with information is encouraged to contact the author at [email protected].

Meet the sculptor tricking New Yorkers with art dedicated to the city's fake history