Immigration Judges Fear Switch To Video Explainers Loses Personal Touch

July 29, 2019, 5 a.m.

In immigration court, there's no guaranteed right to counsel, as there is in criminal court. Translators used to explain the system for immigrants who don’t have attorneys. But there's concern it's now being done by video.

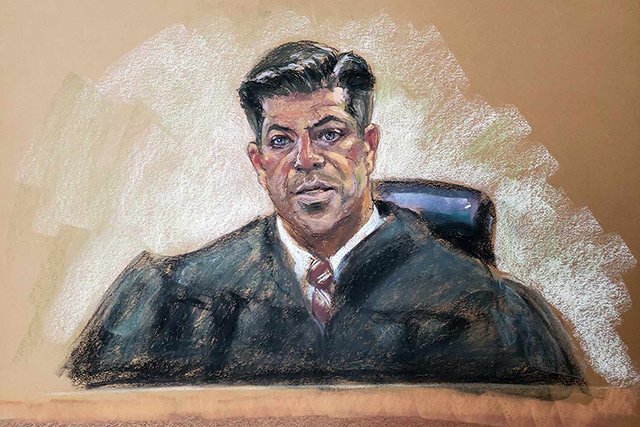

Judge Samuel Factor presides in New York's immigration court and chooses to fill in the blanks for immigrants who don't understand their right to counsel, now conveyed by video.

Immigration court can be overwhelming for a first-time visitor, even with an attorney. A judge will hear 60-100 cases in a single morning, each for about five minutes. It’s just enough time for a lawyer to help a client plead to the government’s charges, explain the next steps and set future hearings, including the trial.

But there’s no right-to-counsel in immigration court, meaning those who can’t afford an attorney aren’t appointed one by the government. For immigrants who come to court without a lawyer, judges have traditionally asked which languages they speak and then found them interpreters to explain how the court system works. They’re then given a list of low-cost legal service providers and some court documents, which are provided in various languages.

This month, a few immigration courts around the country — including in New York City — turned that in-person explanation over to a prerecorded video. It’s in English or Spanish. But it’s not as user-friendly as the video that’s shown during jury duty. Let’s just say the legal jargon of immigration court isn’t nearly as familiar as what viewers see on “Law and Order.”

And there’s something big missing.

“You can't ask a video a question,” said Jeremy McKinney, a vice president of the American Immigration Lawyers Association. “You can't ask a video to repeat something. You can't ask a video to rephrase something to make it clear.”

The Executive Office for Immigration Review, a Department of Justice agency that runs the courts, said it plans to offer the videos in 20 more commonly-used languages. Following the conclusion of the video, EOIR spokesman John Martin said immigration judges will still address each person’s case individually.

“EOIR has not eliminated interpreters, and in-person and telephonic interpreters are available to conduct business after the video advisals are played,” he said. But he also said the agency started using the videos this month in an effort to "improve court efficiency and reduce interpreter costs."

Listen to Beth Fertig's report on WNYC:

This is why the American Translators Association and the immigration judges’ union have both raised concerns about the potential for denial of due process. In a letter to the government, the National Association of Immigration Judges wrote that having a pre-recorded video can be of assistance, but “it is not a substitute for an immigration judge interacting with respondents through an in-person interpreter.”

Judges are used to answering questions from immigrants who don’t have attorneys. But the vast majority of these respondents, as they’re called in immigration court, don’t speak English and need the help of an interpreter. The judges’ union worries that substituting scheduled, in-person translators with telephonic interpreters on a case-by-case basis will put greater demands on its busy members. The union has already complained that EOIR has been cutting back on interpreters for other court hearings.

I saw the video last week during a morning session in New York City’s main immigration court at Federal Plaza. It’s about 15 minutes long and pretty comprehensive. An immigration judge describes which documents are required, how an immigrant risks being deported if he or she doesn’t come to court, and what to do if they move to another city. He also details the term “voluntary departure,” a way for immigrants to return to another country if they don’t want to fight their case in court.

The video explains that a person who files a frivolous asylum application can be barred from any future benefits, and how to file for a work visa.

Some advocates have expressed concern that the video may be confusing for immigrants.

There was only one immigrant without an attorney the day I saw the video in English in Judge Samuel Factor’s courtroom. He was a young man from India who gave permission to publish only his first name, Mandbir. Factor gave him a transcript of the video afterwards, and asked if he had any questions. They then spent about 20 minutes talking about Mandbir’s trouble getting an attorney as he fights the government’s effort to deport him over what he described as a legal problem.

Mandbir was clearly nervous, standing to walk directly in front of the judge’s desk. Factor told him to relax and sit down. He also handed him extra forms in case he had a fear of returning to his country and wanted to apply for asylum. He scheduled Mandbir’s next hearing for the fall and told him his new lawyer could appear by phone if he couldn’t come in person, something that wasn’t explained in the video.

Afterwards, Mandbir said he felt relieved. “I think it answered everything,” he said of the video. But he also said he was glad he could ask the judge more questions. “This is kind of sensitive thing of your life,” he explained. “Your future depends on this.”

On the same day Mandbir’s questions were being answered by Factor, Judge Olivia Cassin was down the hall in another courtroom explaining how immigration court works to several Spanish speakers. An interpreter was there in person.

“It’s very hard to navigate immigration court without a lawyer,” Cassin said, as she held up a thick black book of U.S. immigration law. The way she worded this warning did not appear in the video. “We’re very lucky in New York City to have lawyers who represent people for little or no cost.”

Everyone without an attorney was given a list of providers to call, as required by the government. Turning to one respondent with a young child, Cassin added, “I know that this is hard but you need to help your son.”

Beth Fertig is a senior reporter covering courts and legal affairs at WNYC. You can follow her on Twitter at @bethfertig.

This story has been updated to reflect that the video was viewed last week, not this week.