Hitting the pavement in Harlem with one of NYC’s street psychiatrists

June 23, 2025, 6 a.m.

There are no quick fixes when it comes to helping people in need, outreach doctor says.

Dr. Joanna Fried’s first client of the day on a recent hot June morning in East Harlem was a woman sitting on the curb in a wheelchair under a heavy blanket, which she pulled over her head when she saw Fried approach from across the street.

As a psychiatrist with Janian Medical Care, a group that describes itself as the largest provider of psychiatric services to homeless and formerly homeless New Yorkers, Fried’s work is often an exercise in patience.

“Morning, neighbor,” Fried said cheerily.

“No thank you,” the woman replied from under the blanket.

Janian supplies clinicians to a large network of city-funded, nonprofit-run outreach teams that seek to build relationships with transient New Yorkers — sometimes over the course of months or years — to keep track of how they’re doing and get them to accept help with housing, medical and behavioral health care and other needs.

Fried, whom Gothamist shadowed on a recent morning, is embedded with multiple organizations’ outreach teams, in addition to serving as the medical director of the Manhattan Outreach Consortium, a collaboration among three nonprofits doing street outreach across the borough.

Her boots-on-the-ground work takes place against the backdrop of a swirling policy discussion over expanding involuntary hospitalizations, which has primarily focused on homeless New Yorkers. That debate over how heavily the city should rely on involuntary care recently culminated with state lawmakers passing legislation that codifies a broader set of criteria for when someone can be sent to the hospital against the person's will.

But Fried, who has been with Janian for 15 years, said that while involuntary care gets all the attention, her day-to-day work remains unchanged: She is largely focused on the less-heralded task of slowly building trust with people living on the street, in the hopes that they will accept services of their own accord.

Her main concern, she said, is helping people get permanent, supportive housing with attached social services. But with limited spots and complex criteria for admission, that can take time.

The roughly 3% of homeless New Yorkers who are not sheltered are the “ universe of people who've really been failed by everybody — by family, by social institutions, by government, you name it,” said Molly Wasow Park, commissioner of the city’s Department of Social Services.

The agency houses the Department of Homeless Services, which contracts with homeless outreach teams, most of which now include clinicians like Fried.

“Meeting people where they are” and trying to build a relationship is necessary to get people to come inside, Wasow Park said.

The population Fried works with — people living on the street who may have mental health or substance use disorders — looms large in the city’s political discourse. It’s a group that’s often talked about, including in recent mayoral debates, as a problem in need of solutions. But in her work on the ground, Fried said, she tries to take her cues from the people she’s trying to help.

“One of the nice things about being part of a team is that they are offering the things that people may want more than they particularly want to talk to a psychiatrist or a doctor or take medicine,” Fried said.

Those things could include getting a person’s benefits turned on, getting them a phone, helping them reconnect with family or securing them a single room in a safe haven (a more flexible shelter model designed for people who are averse to traditional, congregate shelters). It could include a sandwich or a pair of socks.

“Anything you want the outreach team to bring you?” Fried asked the woman under the blanket. On this morning, she was traveling solo to check in on people targeted by a team run by the nonprofit Center for Urban Community Services, more commonly known as CUCS.

“No, thank you,” the woman said in reply.

After a few more tries at sparking a conversation, Fried took the hint. Walking away, she said the interaction went exactly how she expected, but she still holds out hope: One time, the woman accepted a bottle of lotion. “ There will be tiny moments where I'm like, OK, maybe that's a toehold,” she added.

Gothamist joined Fried as she made incremental progress with some patients, struggled to locate others and, at one point, took a lengthy detour to make sure a man slumped over on a bench wasn’t overdosing.

She also caught glimmers of hope. One man in transitional housing who came in for an office visit said his weekly therapy sessions with Fried had a dramatic effect on him, helping him to address past trauma, quit drinking and rekindle his passion for writing.

Fried said she works with some patients for just a few weeks before they are handed off to other providers, but gets to stick with others for years — sometimes long enough to see a transformation.

Trying to connect

On this morning, Fried approached one new client she’d been referred to by the CUCS team as he was dozing in an office chair outside a bodega.

“Sorry to wake you,” she said as the man struggled to keep his eyes open. She got him to stay awake long enough to answer a few questions about his medical history, including why he was wearing a hospital bracelet (he said he had a hernia) and whether he had ever taken medication for “stress” or “nerves.”

“Sometimes, somebody has these oral movements that suggest that maybe they’ve been on antipsychotics before,” Fried said. “ I wouldn't necessarily have asked him about psych meds if I hadn't noticed that with him.”

A big part of Fried’s role is to complete the psychiatric evaluations required for supportive housing applications. But she said she also tries to slip in offers of medication, therapy or substance use treatment.

Of the 65 people Fried met with through the CUCS team between May 2024 and May 2025, nearly two-thirds accepted a prescription for medication, according to the nonprofit. But CUCS added that’s not the full array of behavioral health services the team's 455-person caseload received over the past year.

Melissa O’Brien, director of psychiatric services at the nonprofit Project Renewal, which also serves homeless New Yorkers, said some people need to start treatment to even begin to engage in the lengthy process of getting into housing, whereas others may be more open to treatment after they are inside and have some stability.

“It’s very patient-specific,” she said.

To start, Fried just offered the man in the office chair a place to sleep and shower. Her colleagues said he had rejected a placement in a safe haven before, but this time he said he was interested, as long as it was in the Bronx. Fried was eager to tell her team so they could help him make the move.

Wasow Park emphasized that the city’s homeless outreach teams are only as effective as the housing placements they have to offer. She said the expansion of safe havens has been helpful, but agreed with Fried that more supportive housing is needed.

Of the 455 clients the CUCS team served over the past year, 305, or two-thirds, accepted temporary beds, while another 101 moved into some form of permanent housing such as apartments with rental vouchers, supportive housing, or the homes of family members, according to the nonprofit.

When is hospitalization warranted

On her morning route, Fried had less success tracking down a patient whose supply of psych meds had likely run out.

“I’m happy to get you something to eat,” Fried offered the patient in a voicemail, trying to entice her to meet up. After hanging up, she said she had no idea if the medication she’d prescribed the patient weeks ago was working or if it was having any side effects.

Fried has the power to send patients to hospitals for psychiatric care against their will, but said she exercises it infrequently — adding that Mayor Eric Adams’ emphasis on expanding involuntary hospitalization hasn’t influenced her practice.

Embedding psychiatrists not only within outreach teams but also in shelters and housing programs makes involuntary hospital trips less necessary, Dr. Anthony Carino, Janian’s director of psychiatry, told Gothamist in an interview last November. “The vast majority of our clients really respond to that approach,” he said.

Although the new standard was only codified this year, Adams has been instructing police officers and outreach workers to expand their criteria for sending people to hospitals involuntarily since 2022. He says it’s warranted if someone appears to have a mental illness and be unable to meet their own basic needs, not only if they present a danger to themselves or others.

Adams’ rhetoric has largely focused on people staying in the subway and on the street, even though city data shows involuntary removals in the city last year more often originated in people’s homes.

“We’re ensuring more New Yorkers suffering from untreated severe mental illness are getting the help they need, even when they are too sick to know they need it,” said William Fowler, a spokesperson for the mayor. He added that recent changes to state law provide clinicians on the street with “clarity and confidence” to initiate involuntary hospital trips.

But some city council members and mayoral candidates have argued that the emphasis on this particular intervention overshadows the need for investment in a much broader set of mental health services.

“The administration has continuously relied on involuntary removals as a catchall solution,” City Councilmember Linda Lee, who chairs the Council’s mental health committee, said in March.

Fried said she has seen instances when involuntary hospitalization has “resulted in really miraculous, life-changing movement for people.” But in other cases, she said, people quickly end up back in their usual spots on the street.

Still, Fried said, she is more optimistic now than she used to be that hospitalizations will have positive outcomes because of the city’s small but growing number of longer-stay psychiatric units, which allow patients to continue to receive supervised treatment after they are no longer in need of acute care.

NYC Health and Hospitals has opened three such “extended care” units in recent years and is launching a separate residential program for homeless patients being discharged from hospital stays. The state-run Manhattan Psychiatric Center has a small number of beds in similar “transition to home” units.

“ The long-term [hospital] units are fantastic,” O’Brien agreed, though she noted the patient has to want to stay. O’Brien said she still generally views hospitalization as a short-term fix and said Project Renewal’s practice around involuntary removals “ hasn't changed at all” under Adams.

A dramatic change

While outreach efforts can sometimes take years to pay off, Fried said, “We see people who have really dramatic changes.”

Abdi Latif Ega remembers being in a disoriented dream state when he was awoken in Morningside Park at 5:30 a.m. one morning in 2023 by CUCS staff.

Ega, a writer and former Ph.D. candidate at Columbia University, didn’t go into all the details of how he ended up homeless but attributed it to a combination of disillusionment with academia, depression and heavy drinking.

Ega accepted the shelter placement the outreach team offered him right away, he said, but it wasn’t until he began therapy sessions with Fried that he started to unpack the trauma he had from witnessing violence in his native Somalia and to interrogate why he was “self-medicating.”

“With these questions that I was posed every week, it gave me a launchpad to now actually question myself,” Ega said.

While some of the clients Fried sees have diagnoses like schizophrenia or depression, she said she’s most often treating “ some pretty substantial trauma,” whether from being homeless or from experiences the person had before becoming homeless.

Nearly two years after he was first approached by outreach workers, Ega is still in a temporary “stabilization” bed while he works with the team on getting permanent housing. Losing his ID and other documents on the street has made the process tediously slow, he said.

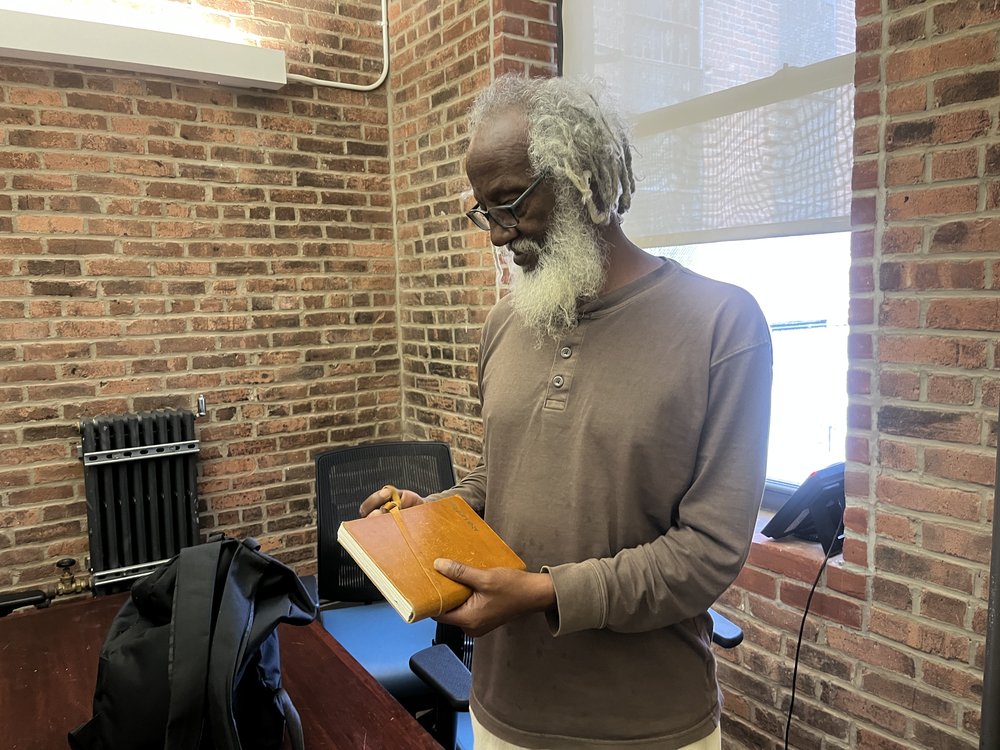

But he credits therapy with now being six months sober and 250 pages into his second novel, which he is writing longhand in notebooks he pulled out to show off his progress.

“It’s really gratifying to see somebody access the things about themselves that maybe they had to turn away from” while they were just trying to survive, like being a parent or an artist or a music lover, Fried said.

She said she attributes those wins, when they come, to the full spectrum of services her teams offer — not mental health treatment alone.

Involuntary commitments start far more often in NYC's homes than public spaces, data shows Adams renews bid for easier involuntary commitments after Manhattan stabbing deaths