Free Mets Tickets For Hardened Criminals? Don't Believe The Hype

Nov. 15, 2019, 11:06 a.m.

Mets tickets are rare—more common are money for MetroCards so poor defendants can afford to make their court dates.

A run-of-the-mill supervised release program was transformed into a viral hit last week. “Gift cards, cell phones and Mets tickets: How NYC spends $12M enticing criminals back to court,” blared the New York Post headline of one of three stories written in the span of a few days about this three-year-old program.

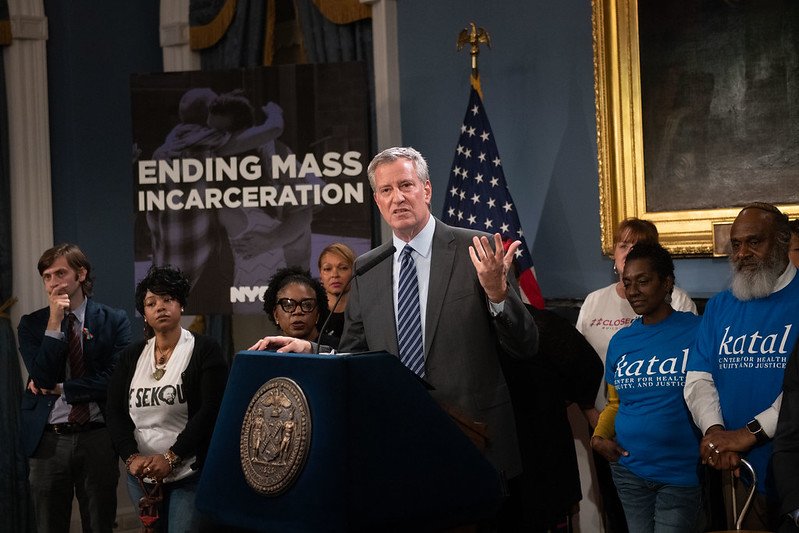

“Little luxuries” offered to “jailbirds” include gift cards to Burger King, Applebee’s and Target, the Post wrote. The only discernible news hook in any of these alarmist stories—“De Blasio doesn't know how much his Mets tix-for-court appearances cost” cried another headline—is New Year’s Day, when a host of criminal justice measures, including an end to cash bail for most misdemeanors and nonviolent felony offenses, go into effect.

Fearmongering around criminal justice reform is not new for tabloids, particularly the Post, a mouthpiece of the revanchist right. Whether it was the city’s push to reduce the absurdly high amount of high stop-and-frisks or efforts make questioned people more aware of their constitutional rights, the Post has reliably railed against the mildest of change. Local TV news, too often taking their cues from tabloids, adopt the same ill-informed approach.

This disinformation campaign is effective. “You say public safety, but giving them gift cards and Mets tickets is not providing safety,” Tiffany Griffin, the aunt of 14-year-old Aamir Griffin, who was shot and killed on a basketball court last month, told Mayor de Blasio at a town hall meeting this week.

Here’s how the program actually works. Instead of setting bail on certain defendants, judges can place them in supervised release where they will be monitored in the community, linked to voluntary services, and notified of future court dates.

This allows defendants to still see their families and stay employed while awaiting trial. Defendants who are ultimately innocent don’t have to face a choice between pleading guilty to a crime they didn’t commit—more than 90 percent of cases don’t go to trial—or rotting in a substandard, torturous jail facility, like Kalief Browder. They can go home and await their day in court.

And Mets tickets are rare—more common are money for MetroCards so poor defendants can afford to make their court dates.

But, let’s say for the sake of argument, baseball tickets were the primary incentives offered. Supervised release still works. According to the city’s 2019 scorecard, participants in the program overwhelmingly make their court dates: the citywide court appearance rate was 88 percent. While intakes into the program increased by 54 percent from 2016 to this year, the appearance rate has held steady at 88 percent.

Jonathan Monsalve, the project director for Brooklyn Justice Initiatives, the nonprofit operator of the supervised release programs in Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Staten Island, told Gothamist that through September, 94 percent of defendants in those boroughs have made their court dates.

“Bail was designed to make sure people come back to court,” Monsalve said. “Our program, since 2016, has proven that with the support of social workers, case managers and other stuff, people can come back to court with great frequency.”

What supervised release has proven, Monsalve added, is that cash bail “isn’t necessarily helpful and is biased against low income folks who come from specific neighborhoods and socioeconomic backgrounds.”

There are obvious moral arguments to make against caging people—an overwhelming majority of them black, brown and low income—who haven’t been convicted of any crime, especially those who are left to suffer in places like Rikers Island because they can’t afford bail. The Post and their allies are unlikely to be moved by those arguments. It’s not as if they are current victims of overzealous prosecutors, backlogged courts, and heinous jails.

Conservative critics of criminal justice reform, however, tend to be obsessed with fiscal matters. And it’s here the complaints about supervised release really begin to lose all logic.

In 2018, the annual cost per detained person in New York City was $302,296, or $828 a day. Last year, the average daily jail population in the city was 8,397. The math is easy enough to follow, even for the disingenuous: a population of that size costing that much equates to almost $7 million in one day alone. The bail reforms coming into place in the new year are expected to cut into these exorbitant costs as less people go to jail.

When crime was higher and the destructive impacts of incarceration were not acknowledged by most mainstream politicians, inflammatory criticism could easily sink attempts at reform. In the new era, it’s the law-and-order set who are on the defensive, losing ground as the system slowly grows more humane and crime remains low. What to do when every warning of blood on the streets doesn’t come to pass?

It’s likely 2020 will be another year of inciting fear, without evidence, against reform. And it won’t just be tabloids. Like his predecessor, Police Commissioner Dermot Shea thinks “keeping people safe” cannot be accomplished while phasing out cash bail, despite a lack of surge in crime after New Jersey ended cash bail two years ago. Prosecutors are already scheming over ways to weaken new discovery laws that have already worked in places as conservative as Texas.

Expect more bad faith attacks on reform measures and the NYPD to do whatever it can as a fairly autonomous standing army of 35,000 to resist change. More fights are on the horizon. The law-and-order set are ultimately losing the war of politics and public opinion, even with a newspaper and traditionalist TV at their side. But they won’t go quietly.