Forged signatures found on Mayor Adams’ petitions to run as an independent

Aug. 1, 2025, 6:01 a.m.

The Adams campaign said it is conducting a review after Gothamist found signatures that were fraudulently obtained or outright forged.

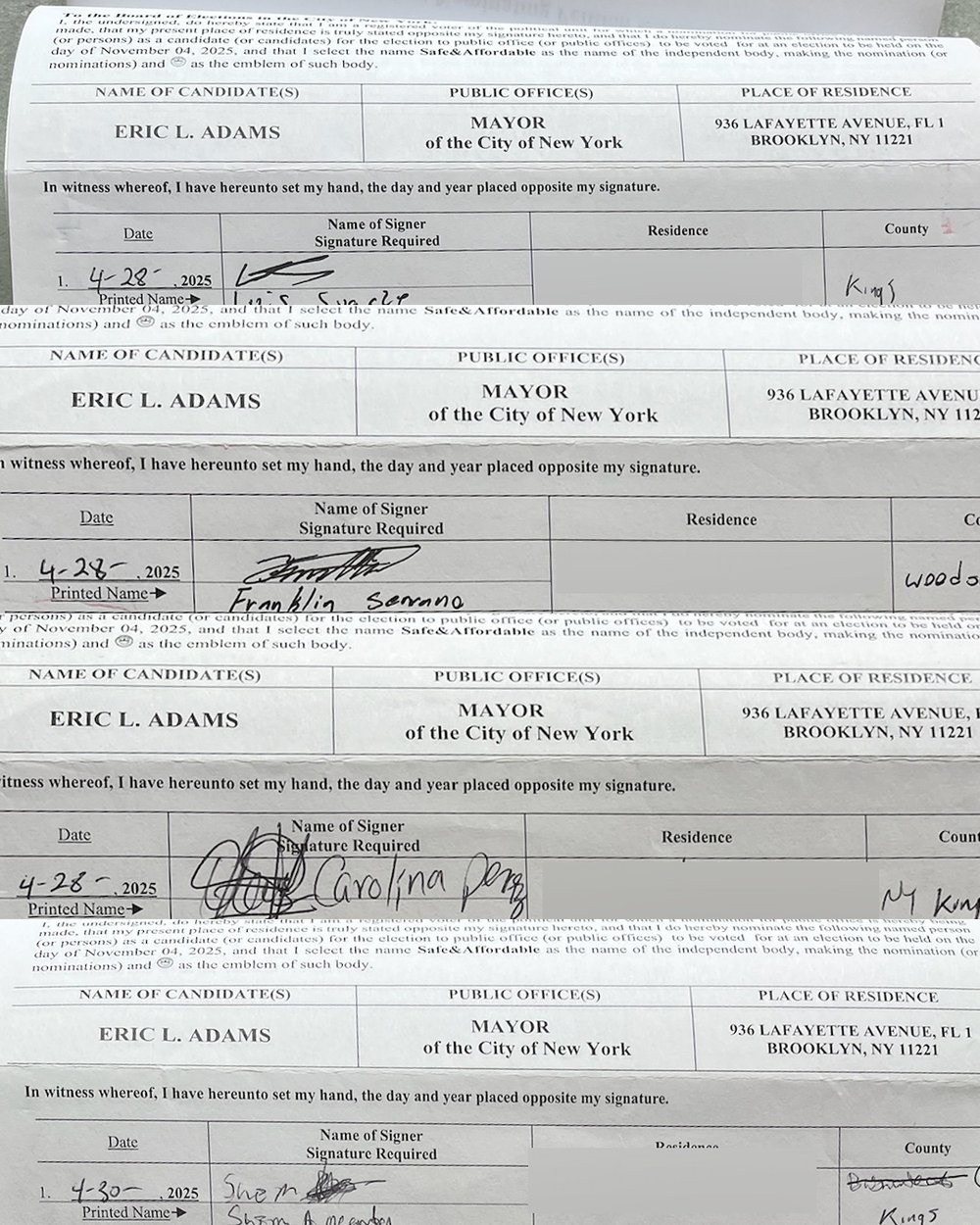

Mayor Eric Adams’ re-election campaign submitted faked and fraudulently obtained petition signatures in his effort to secure a spot on the November ballot as an independent candidate, a Gothamist investigation has found.

Gothamist reviewed signatures submitted from across New York City and found people who said their names were forged, as well as people who said they were deceived into signing the petitions. In at least three instances, the campaign turned in signatures from dead people.

Under state law, Adams needed to submit at least 7,500 signatures from voters who wanted him on the general election ballot as an independent. The tactic enabled the incumbent mayor to avoid a crowded Democratic primary race that was shaping up as a referendum on the federal corruption charges he once faced and his growing ties to President Donald Trump.

The Adams campaign hired several companies to deploy employees across the city and gather signatures of registered voters in New York City who supported the mayor's re-election.

Signature gatherers were required to sign a form pledging that each signature they collected was from the person whose name appeared on the sheet. But an executive from one company said he also warned the Adams campaign and other vendors it hired that they should run additional quality control measures – a suggestion he said the campaign rejected. In response to Gothamist's inquiries, the campaign said it expected the companies it hired to follow the law but nevertheless pledged to now conduct its own review of the signatures.

In all, Gothamist identified 52 signatures that were fraudulently obtained or outright forged, but thousands more have not been vetted. Verifying signatures is time-consuming work; for two weeks, three reporters knocked on more than 200 doors in four boroughs and interviewed more than 100 people. In some buildings, the majority of the people we spoke with said their signatures had been forged.

There are other reasons to believe there may be many more problematic signatures. The fraud uncovered by Gothamist was committed by at least nine workers who together submitted more than 5,000 signatures.

Many of those workers declined to answer questions about their work, citing nondisclosure agreements they signed with signature-gathering companies.

The discovery is unlikely to affect Adams’ candidacy. Ballot petitions receive little, if any, scrutiny from city election officials. Rival mayoral campaigns did not challenge their validity before a June deadline, and Adams turned in nearly 50,000 signatures in hopes of appearing on two newly created ballot lines — well more than the 7,500 required per ballot line.

However, the bogus signatures point to a vulnerability in an elections system that is likely to be tested in the future as candidates look for ways to circumvent the ranked-choice primary system. Adams is among several independent candidates in the upcoming November election, along with former New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who lost the Democratic Party nomination to Zohran Mamdani.

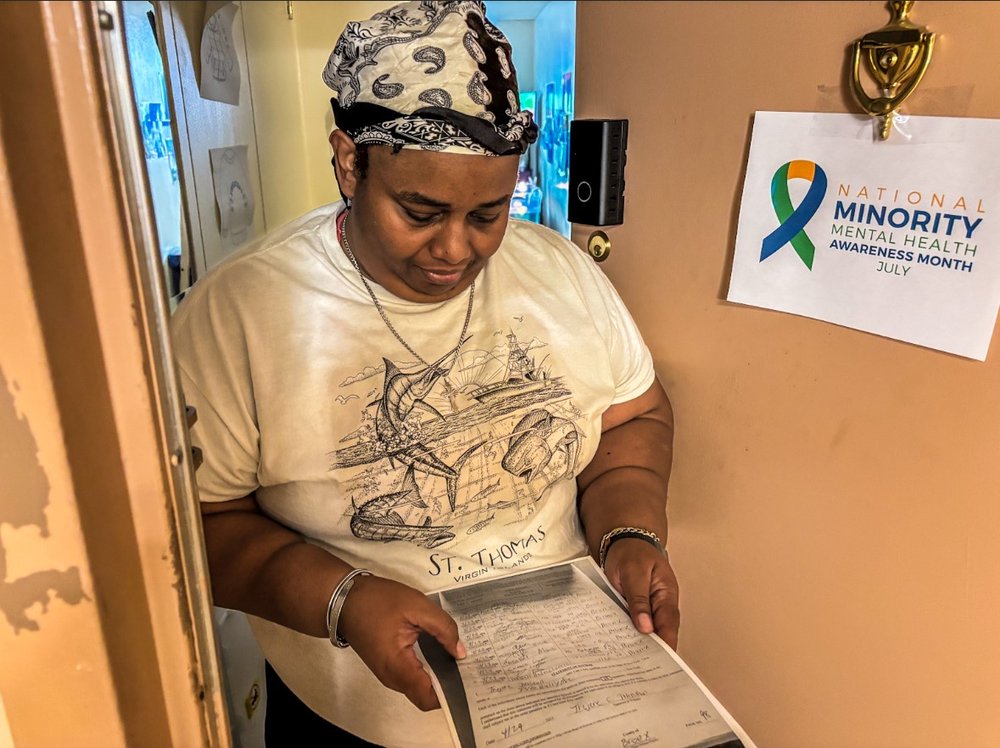

That’s little comfort to Bronx resident Jahmela Brooks, who said she was out of the country on the day she supposedly signed the petition.

“ This is shocking. It's tough to even put it into words,” Brooks said as she examined what she said was her forged signature. “I’m beyond angry.”

Officials do not vet petitions

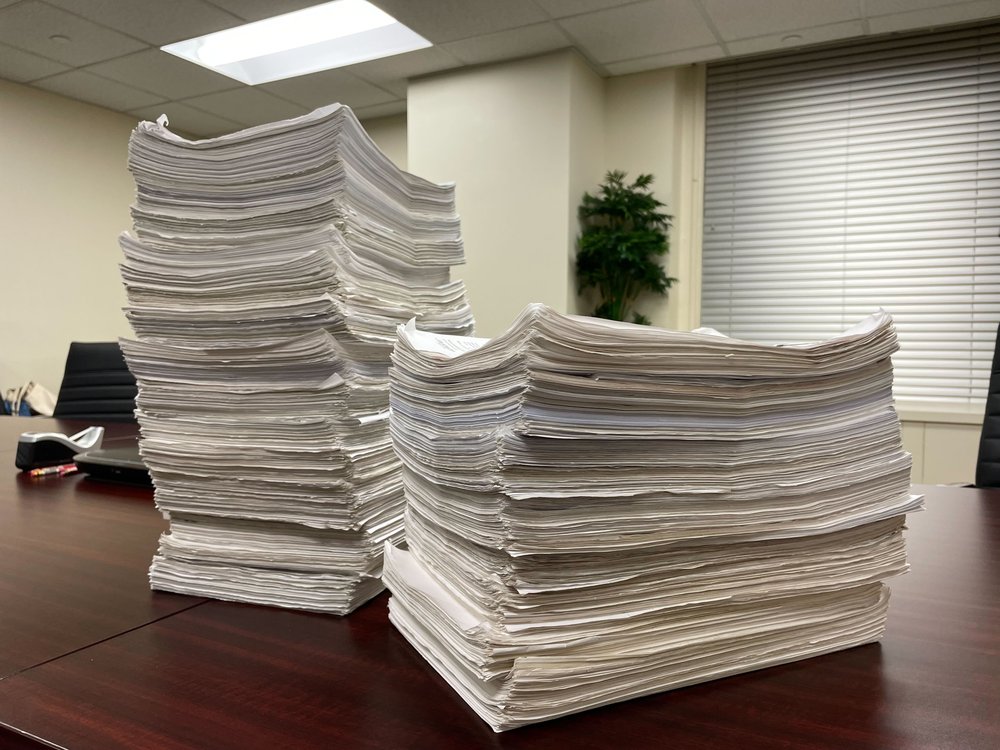

To investigate this story, Gothamist reviewed thousands of pages of signatures submitted by the Adams campaign and held at Board of Elections offices in Brooklyn and Queens.

We found unusual patterns. Some pages had strikingly similar handwriting among many residents in a single building, for example. Others showed a single campaign worker collected more than 700 signatures on a single day.

Reviewing ballot petitions requires tedious, labor-intensive work, and it’s one of the reasons they undergo little scrutiny. The Board of Elections is only required to certify whether a candidate submitted a sufficient number of signatures, but it does not verify their authenticity.

Campaign experts said it’s common for some invalid signatures to be collected by candidates seeking to get on the ballot. Many campaigns perform their own spot checks to verify the validity of signatures, said veteran election law attorney Jerry Goldfeder.

But he said it’s “very rare” for repeated instances of fraud to appear on petitions for an incumbent seeking re-election to an office as prominent as mayor of New York City. He said petition problems are more common for new candidates running for lower office.

“ Every now and again, somebody tries to cut corners and they're generally caught and sometimes those cases are referred to the district attorney or the U.S. attorney, and there are prosecutions,” said Goldfeder, who chairs the American Bar Association’s Election Law Committee.

In response to questions from Gothamist, an attorney for Adams said the mayor did not direct anyone to break the law, and that his campaign would “determine whether any corrective action is warranted.”

A stack of dubious documents

The River Park Towers rise 428 feet above the Major Deegan Expressway, overlooking the Harlem River. They’re the tallest buildings in the Bronx and home to about 5,000 people. They were also a hot spot for at least one Adams campaign worker whose petition forms included fraudulent signatures.

Trejere Johnson submitted at least 110 signatures from the complex that were said to have been collected on April 29 and 30, according to petition records. Despite multiple attempts, he could not be reached at his listed address or by phone.

It’s unclear which of several contractors hired by the Adams campaign employed Johnson and many other signature gatherers.

Gothamist visited River Park Towers and found only one person whose name appeared on petition forms for Adams and who recalled signing them. Gothamist spoke with 15 others over the course of three hours who said their signatures had been forged. Four supposed signers no longer lived in the complex. Three residents said they did not know the signers listed on Adams petitions as living in their apartments.

Tanya Carmichael, a Republican Party district leader who lives in the complex, was among those who said their signatures were forged.

“That’s not my signature, not at all,” Carmichael said after she was shown the petition by a Gothamist reporter. “It’s not even spelled correctly,” she added, pointing out the signature was written as “Thanya.”

Carmichael’s neighbor Liana Santiago was also listed as having signed. Not only did she say the signature wasn’t hers, she said she had never heard of another person whose signature also appears on the petition — and who supposedly lived in her apartment.

“I don't write like that at all,” said Santiago, pointing to a first initial and scribbled last name on the petition. She compared it to her actual signature, a distinct cursive with her first name spelled out with a large looping L. “That sucks, whoever did that.”

Mercedes Dabulis, a nurse who lives in the Bronx complex, scoffed at the signature attributed to her, which was written with low slopes and compact initials.

“It looks like fraud,” she said.

Dabulis then demonstrated on a piece of paper how she signed her name. Her signature had tall, sharp peaks in the M in her first name, which she wrote out in its entirety.

Similar patterns in Queens

The River Park Towers were among several high-rise apartment buildings — many of them NYCHA complexes — where residents were surprised and angry to learn their names appear on Adams’ forms.

“ I don't care who the person is, I'm not going to sign any petitions,” said Peter Koch, a 75-year-old resident of the Pomonok Houses in Queens. He said he was surprised to see his name on the list because he refuses to sign any candidates’ petitions. “If this is for Mayor Adams, it’s telling you who not to vote for.”

Eight current and former residents of the Pomonok Houses told Gothamist their signatures were falsified. Reached by phone, two of the people whose names appear on the forms said they don’t live in the building.

One, Sarah Samy, said she moved 10 years ago and now lives in Long Island City. Another, Ryan Burrell, said he lives in South Carolina.

All of the fraudulent signatures from Pomonok Houses were submitted by Robin Dorsett, a campaign worker who submitted at least 150 signatures in total from Queens. Dorsett could not be reached by phone or at a listed address.

More than a dozen residents of Morningside Gardens, a complex of six 21-story apartment buildings in Upper Manhattan, said they either did not sign a form endorsing the mayor’s independent candidacy, that they were tricked into signing for Adams, or that the people who allegedly signed did not live at their address.

Leila Lieberman, 93, was stunned to learn her stepson, Adam, supposedly signed the petition and listed her apartment as his address.

He died by suicide in 1997, she said.

“I’m sure that they [politicians] do things to get on the ballot, to get elected, but that is something they shouldn’t have done,” she said.

Franklin Sendra, a campaign worker who submitted more than 50 signatures from the building, including 12 that residents said were forged, declined to discuss the matter when reached by phone, saying he signed a nondisclosure agreement as part of his work.

According to an executive at one of the companies hired by the Adams campaign, Sendra worked for MY Br&, a Manhattan-based marketing firm that Adams paid more than $220,000 for petitioning and canvassing.

Julian Hill, who oversaw teams of signature gatherers as the company’s director of field operations, recognized Sendra’s name from a list of campaign workers who collected petitions for Adams. Hill said that the company did not permit its workers to forge signatures or deceive signers. But he also said it did not review every petition form to verify the authenticity of signatures.

“Because of the timing of when the actual signatures come in, it's so hard,” he told a reporter.

After Gothamist spoke with MY Br&’s CEO David Vassel, Hill called the reporter back to say the company does review each signature.

And according to another contractor, the campaign was warned fraud could be a problem.

Quality control concerns

Another signature-gathering firm hired by the Adams campaign was Public Appeal, a Wyoming-based company led by two brothers from Texas, Trent and Trey Pool. The Pool brothers have worked for several national campaigns, and they also personally gave a combined $3,100 to Adams’ re-election bid.

The campaign paid their company $175,000 to gather signatures, making Adams the only mayoral candidate to hire an out-of-state firm for the service.

But Trent Pool said there was disagreement between his firm and the campaign.

Public Appeal used an outside auditor to vet around 15,000 signatures it collected for Adams, Pool said. He said he encouraged other vendors and campaign officials — including Adams’ close confidant and former City Hall adviser, Ingrid Lewis-Martin — to do the same with the ballot petitions other companies were collecting.

“We offered for the other vendors to use the same service but they refused,” Pool told Gothamist in a written statement, adding that other vendors for the campaign told him “it was the state’s job to prove fraud — not ours.”

Lewis-Martin resigned from the Adams administration late last year after Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg’s office charged her with bribery. She has pleaded not guilty and has since played a role in the mayor’s re-election campaign. Her attorney Arthur Aidala said he did not think she was involved with the campaign’s petition process.

Vito Pitta, an attorney for the Adams campaign, said all of the firms hired to collect signatures were expected to follow the law.

“Any individual or subcontractor found to have violated legal or ethical standards should be held accountable,” Pitta said. He would not disclose what law firm had been retained to review the thousands of signatures submitted by the campaign because a contract had not yet been signed.

Forged signatures are clear indications of petition fraud for any auditor. But election experts say other forms of wrongdoing are harder to detect.

The folded petition approach

Public Appeal came to the attention of the Adams campaign because the Pool brothers had experience working on big national political campaigns, according to Pitta. The siblings worked on Robert F. Kennedy Jr’s effort to run for president as an independent candidate.

What Adams didn’t know, Pitta said, was that Trent Pool and one of his companies had become entangled in legal problems.

Last year Pool was charged with strangling and assaulting his girlfriend at a SoHo hotel. He pleaded not guilty and the case is still pending. Adams’ campaign said it terminated its contract with Public Appeal after Gothamist reported those charges in June.

But there were other problems. In September last year, a state court in New York found that a subcontractor for one of Pool’s other companies, Accelevate, had used a fraudulent signature-gathering tactic in which collectors hid Kennedy’s name by folding down the top of the petitions.

“The name of the candidate at the top of the petition was concealed,” said Jared Kasschau, a lawyer who led the lawsuit against the Kennedy campaign on behalf of two voters.

Petitions submitted by the Adams campaign showed similar signs of folding on more than 100 forms — most bearing 10 voter signatures apiece — with visible creases right below the mayor’s name.

Many of those forms were collected by Phillip Harris. Pool confirmed Harris worked for Public Appeal on both the Adams and Kennedy campaigns.

Records show Harris submitted nearly 2,000 signatures for Adams in total. Pool said his firm paid for a small number of Harris’ signature sheets but that he had also warned Harris and other vendors about turning in folded petition forms.

When reached by Gothamist, Harris denied folding the forms to trick people, although creases are clearly visible below Adams’ name on documents he submitted. But he acknowledged that some signature collectors were not forthcoming when trying to get people to sign for Adams.

“A lot of people won’t say [Adams’] name and just say it’s to get an ‘independent candidate on the ballot,’” Harris said.

Eight people whose names appeared on forms collected by Harris told Gothamist that they had no idea they signed a petition for Adams.

“I do remember being on the subway and someone coming up, and I was just told it was to get a candidate on the ballot,” said Brooklyn resident Megan Oots, adding that she did not see Adams’ name on the form. “I collected signatures for [Zohran] Mamdani. I definitely wouldn’t have signed for Adams. He’s a crook.”

Signatures for hire

In the race for signatures, independent political campaigns often rely on a niche industry of canvassers who move from place to place like seasonal workers. Records at the Board of Elections show at least 18 signature gatherers for the Adams campaign listed the campaign attorney’s Manhattan office as their local address.

North Carolina resident Scott Elam said he was hired to work on Adams’ campaign by the company Ballot Access Pros. He paid for his own flight to work in New York City, he said, and shared an Airbnb rental in Bayonne, New Jersey with other signature gatherers who ventured into the city each day.

“The majority of my team members are functionally homeless,” Elam said. “They have family they can stay with, but they don’t have cars, they don't have homes. They're on the road.”

Records show Elam submitted more than 500 signatures for Adams. He did not collect any of the forged signatures or folded petition sheets uncovered by Gothamist.

He declined to answer specific questions about his work for the campaign, citing a nondisclosure agreement. But he said he and his colleagues were expected to turn in 100 signatures per day. If a worker turned in only 20 signatures in a day, they could be sent home. More than 100 per day would put them in a position to negotiate a higher daily pay rate, Elam said.

State law prevents companies from paying workers per signature. However, many signature-gathering companies find other ways to motivate workers, offering incentives that election experts say skirt the border of legality.

Ballot Access Pros’ website says that it uses a per-signature “points system” that workers can redeem for things like merchandise, iPhones or cruises.

“We often run competition days as well with massive points giveaways!” according to an FAQ on the company’s website.

Attorney Douglas Kellner, who served for 30 years as a commissioner for both the New York city and state elections boards, said companies skirt the law by giving bonuses for good performance or meeting quotas.

“All of that’s borderline,” Kellner said. “The statute is clear: You can’t pay by the signature.”

Ballot Access Pros founder Charles Eden said the incentives listed on its website do not apply to every political campaign and that the company’s signature gatherers were paid by the hour as required by New York law.

“While we have expectations of our workers it did not impact compensation,” Eden wrote in an email.

The Adams campaign also said it did not encourage the contractors it hired to flout these rules and that the companies were required to pay workers by the hour, not by the signature.

“There were no quotas or signature-based incentives imposed by the campaign,” said Pitta, the campaign’s attorney.

Legal ramifications of signature fraud

In September 2024, federal prosecutors indicted Adams on charges of bribery, conspiracy and campaign finance violations. Adams was accused of stealing public money via the city’s generous matching funds program.

Adams’ trial was scheduled to take place just months before the Democratic primary, and a growing number of figures at the highest level of the mayor’s own party called on him to resign.

But Trump’s victory changed Adams’ fortunes. As president, his Department of Justice ultimately forced the dismissal of Adams’ case, saying the mayor was needed to help implement Trump’s anti-immigration agenda.

In Adams’ telling, even though the charges were dropped, the case had irreparably harmed his chances of winning the Democratic nomination. One day after the charges were dismissed, the mayor — who once described himself as the “Biden of Brooklyn” — announced he’d skip the primary and run in November as an independent on two newly created ballot lines: “EndAntisemitism” and “Safe&Affordable.” The Board of Elections has ruled that he must choose one to appear alongside his name on voters’ ballots.

It appears certain that will happen even in light of the apparent fraud. Voters and rival political candidates have less than a week after petitions are filed to challenge their legitimacy through the Board of Elections. Outside of that process, allegations of signature fraud can also be litigated in the courts. The deadline to file a lawsuit was June 10.

Kellner, the former elections commissioner, said it’s now up to local prosecutors to investigate allegations of falsified signatures. None of the city’s five district attorney’s offices would comment on whether they’ve opened investigations.

“Petition fraud is a crime, it’s a felony,” Kellner said.

Elijah Hurewitz-Ravitch contributed reporting.

Correction: This story was updated to correct the details of a quote from Trent Pool. He said other vendors told him, “it was the state’s job to prove fraud — not ours.”

Mayor Adams hired campaign consultant accused of strangling girlfriend in SoHo hotel