East River Park Rebuild Plan Is A 'Joke,' Say Lower East Siders

July 18, 2019, 3:50 p.m.

'Whatever the park is giving us, you’re going to take it all away,' said Yvette Mercedes, a Baruch Houses resident, whose children play in the park. 'We need fixing, but why do it all at once?'

City Hall's plan would use landfill to raise most of East River Park by eight feet.

The first stage of City Hall’s East Side Coastal Resiliency project to fortify lower Manhattan against future climate catastrophe is focused on East River Park, which the city has targeted for a massive overhaul to raise the landscape by eight feet from Montgomery Street to East 13th Street.

At a public hearing on Wednesday evening at Mt. Sinai Beth Israel, hosted by Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer, residents of the Lower East Side and surrounding neighborhoods made clear that they are not at all on board with the city’s plan, which they consider a bait and switch that could cost them their local park for an extended period of time.

“We need flood protection, but I don’t approve of the wasteful plan the city is giving us,” Anne Boster, an East 4th Street resident, testified at the hearing. “It will also waste the millions spent recently on the renovation of the track. We can’t be without a park for three and a half years. What a joke.”

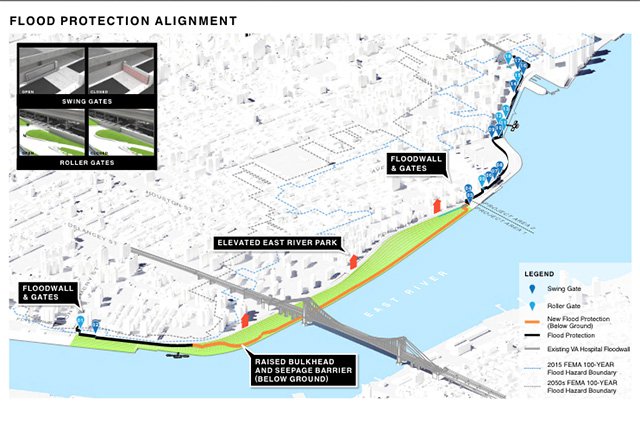

The city’s original plan was to construct flood barriers and berms along FDR Drive. But in September 2018, the city changed course to a design that could be implemented more quickly and raise more of the park above storm-surge levels. The revised plan includes elevating the park by eight feet using landfill, reconstructing its entry points and connecting bridges, redesigning the drainage system along the coastline, and installing flood gates at key locations.

Along the way, the estimated cost of the project—which would be funded by the state and federal government—rose from $760 million to $1.45 billion.

City agencies now plan to close the entire park starting in March 2020, with the project slated for completion by late 2024.

The 45-acre park is a popular running destination, home to numerous youth sports leagues, and a community space where residents barbecue and host parties in the summer. Many neighborhood residents wore sashes which read “Tree Protection Area” and “Do Not Cut” in protest, and the room continuously booed city officials during their presentation.

“Whatever the park is giving us, you’re going to take it all away,” said Yvette Mercedes, a Baruch Houses resident, whose children play in the park. “We need fixing, but why do it all at once?”

Over 25 people testified at the hearing, and expressed their anger at how City agencies—the Department of Design and Construction, and the Department of Parks and Recreation—are handling the project.

The complete park closure, and health hazards brought on by the dumping of landfill are the two most contentious points among residents and city officials. Residents have also pled with city officials for a “greener” plan that is not only flood-safe, but environmentally friendly.

At a previous city council hearing in January, city officials apologized for not communicating clearly enough with residents. "Did we communicate the change properly? No," said Department of Design and Construction commissioner Lorraine Grillo. "That's on me. I take responsibility for that and I apologize." But despite additional open houses for community feedback since then, residents complain that they city’s updated plans haven’t accommodated their concerns.

Also testifying against the current plan were State Senator Brad Hoylman and State Assemblymember Harvey Epstein. Both politicians requested an independent expert panel to assess the situation.

“We have a lot of questions, not a lot of answers,” said Hoylman. “I think it is very important that we have an independent, community based monitor for this project.” He also threatened potential legal action because the city did not ask the state to alienate the parkland, as is required when parks are converted to non-park uses: “That is the prerogative of the state of New York. We wished you would have pursued it, and now we think this whole thing may end up in a lawsuit.”

Another major concern that residents pointed out is the potential loss of biodiversity and ecological damage that would come with razing 981 mature trees in order to raise the park’s ground level. Amy Berkov, an Assistant Professor of Biology at The City College of New York and longtime East Village resident, called the project’s Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) “inaccurate” and said it makes “unjustified assumptions.”

“The DEIS mentions one rare bird species, the peregrine falcon,” said Berkov. “Citizen science records have documented nine birds, and one bumblebee, that are on New York State’s natural heritage program list of endangered species.”

Officials from the Department of Design and Construction and the Department of Parks and Recreation did not respond to specific testimony, but said they will continue to seek public feedback regarding the project. The City Planning Commission will hold its hearing on the project on July 31, with a city council vote on final approval expected to follow in September.

“We’re trying to balance the concern of protecting the neighborhood from climate change, and concerns about disruption,” Deputy Commissioner of Design and Construction Jamie Torres-Springer told Gothamist following the hearing. “In this case, we came to a conclusion that we can’t deliver the project without a full closure of the park. It is very unfortunate.”