East Harlem families facing eviction by MTA to make way for Second Ave subway

July 31, 2025, 6 a.m.

The MTA has promised to bring a new subway to East Harlem for decades. Now, some residents are being forced out of their homes to make way for the long-delayed project.

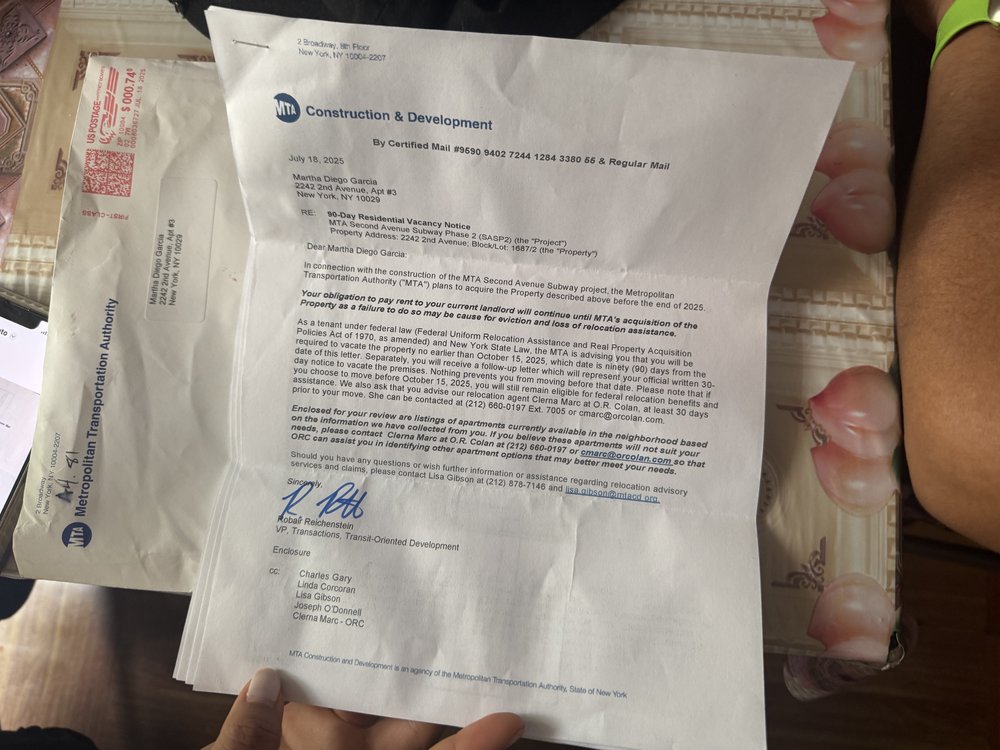

A family in Spanish Harlem received a letter in the mail from the MTA earlier this month with a menacing subject line: “90-Day Residential Vacancy Notice.”

The Diegos — a family of five — have been in the neighborhood for decades. Since 2018, they’ve lived in their building at East 116th Street and Second Avenue, which has an ocean blue facade that’s famous in the area because it includes a mural of fish. The ground floor is shuttered, but was once a popular seafood market.

Now, construction to extend the Second Avenue Subway into their neighborhood means they’ll have to leave for good by Oct. 15. The transit agency is seizing their building via eminent domain to build a new 116th Street station on the Q line in its footprint.

The MTA offered the family some help with finding a new place: a list of apartments, a real estate agent and financial assistance to cover moving costs. Most of the apartments suggested by the agent are hundreds of dollars more expensive than their current monthly rent of $2,900, which is supported by two subletters who rent out rooms in their home. The family said the majority of the options offered by the agent were no longer on the market.

“We’re in shock. So we tell the people that live upstairs and downstairs the news that we’re finding out and they’re also in shock,” said Jocelyn Espinoza Diego, the family’s eldest daughter. “They’re scared. They’re surprised because we haven’t heard nothing from the landlord.”

Court records show the building is one of at least 19 properties that will be taken over for the long-awaited Second Avenue subway construction slated to begin in the coming years. The MTA has gone to court in the last month to seize the buildings via eminent domain to make way for the new subway line, which has been promised to the neighborhood for a century.

The $7.7 billion project is designed to bring much-needed subway service to one of Manhattan’s largest transit deserts and poorest neighborhoods. But in the process, dozens of longtime residents like the Diegos and their neighbors are seeing their lives upended — and suddenly thrust into the dog-eat-dog world of New York City apartment hunting.

Two other large families live in the Diegos’ three-unit building, and they’ve all received the same letter informing them that they’re expected to leave.

“Delivering a project this important and ambitious necessitates acquiring space. Our team has exceeded federal requirements for relocation support services, and we’re committed to giving tenants and businesses the support they need to find a new location,” MTA spokesperson Kayla Shults said in a statement. “East Harlem deserves the Second Avenue subway, and we’ll continue to be a good neighbor as we build it.”

The Diegos said they were first warned they’d have to move in April 2024 when a pair of MTA representatives knocked on their door to tell them the Second Avenue subway extension was finally moving forward. Jocelyn Diego said the MTA employees promised to follow up in writing days later with further instructions. But that follow-up would take months due to a political maneuver by Gov. Kathy Hochul ahead of last November’s election.

Weeks after the MTA employees visited the Diegos, Hochul would indefinitely pause the planned June launch of the MTA’s congestion pricing tolls. The agency relied on revenues from the program to pay for the subway extension. Hochul at the time said her decision put her on the side of “hardworking New Yorkers” who couldn’t afford the tolls, which eventually launched in January. But it also left the Diego family waiting for the MTA to tell them when they would finally have to move.

Martha Diego, the family’s mother, worried how they’d make ends meet if they had to move into a more expensive apartment. She said any short-term support the MTA provides the family won’t be sustainable in the long term when their housing becomes more expensive.

“The rent is being raised everywhere. It’s getting more expensive and for us, here, we’re already used to this rent. And we work a lot for the rent here. So if we move out, it’s twice as hard,” Martha Diego said in Spanish.

Jocelyn Diego and her father, Juan Diego, work as a cashier and cook, respectively, to pay their rent.

“We’re definitely in limbo. It’s too much to process, and not only that, we’re just hoping that they find us an apartment because at the end, me and my mom feel like [the MTA] have the responsibility to find an apartment,” Jocelyn Diego said. “I don’t think it’s fair, because people live here. I feel like people that live here should also have the right to speak up. This was all caught off guard.”

Many of the family’s neighbors who are also set to be displaced said they’ve lived in East Harlem for decades.

The building’s residents said they felt misled by their landlord after the MTA employees first came knocking last year. The Diegos said the transit employees gathered the family at their kitchen table, and collected their social security numbers and information. Martha said she was also told to sign documents in English that she couldn’t understand. The real estate agent connected with the family is a Spanish speaker.

The family said the building’s landlord, Nasir Sasouness, told them not to worry because his building wouldn’t be purchased by the transit agency. According to the Diegos, Sasouness made a point to remind them to continue to pay their rent.

“So we felt safe. We are like, ‘Oh, these people are coming to our house, they’re probably crazy,’” Jocelyn Diego said.

Sasouness declined to comment on the account provided by the Diegos. Sasouness owns several properties in East Harlem, and claimed many of his tenants stopped paying their rent when they found out they’d be acquired by the MTA.

According to a letter that residents received from the MTA, a failure to continue paying their rent may be cause for eviction and loss of relocation assistance.

“It’s unfortunate that the MTA is taking my buildings. It’s a big lot,” said Sasouness. State law requires a judge to determine the fairest price for an eminent domain proceeding, or where a government agency mandates the sale of private property.

According to Ken Fisher, a real estate development lawyer in New York City, the owner and government agency can negotiate the best price for a property based on an evaluation of the zoning and market rate.

“ In most cases, the property owner will commission their own appraisal if they can negotiate a settlement,” Fisher said. “It's a little bit more complicated, but can be a relatively straightforward process. If they don't [settle], then it will go to a court. Both sides will put their experts on and the judge will decide.”

The Diegos said they’ve paid their rent on time since finding out they’d be forced from their building.

But the family’s problems go deeper than the loss of their home. Their youngest son Anthony is diagnosed with autism and enrolled in an East Harlem school where his special needs are met. If they’re forced to move to a new area of the city, they said he’d have to drop out — and adjust to a whole new school environment.

The displacement isn’t exclusive to East Harlem’s residents. Several commercial buildings along the planned Second Avenue extension — which will add three new stations ending at East 125th Street and Lexington Avenue — have already been torn down ahead of the project. Several business owners along the route feared they’d lose money due to construction, even though their buildings aren’t being seized by the MTA.

The same block between East 115th and 116th streets where the Diegos live is home to two barber shops, a pharmacy, deli, a 7/11, an African clothing store and a tile store.

Lu Nicaj, the owner of Eagle Tile, said while the MTA isn’t demolishing his shop, he believes upcoming work to build a new subway station on the block will kill his business.

“Whether I’m going to even survive the process as a business owner here, I don’t know,” Nicaj said at the front counter of his store. “Because business has been slow as it is, and not to mention now, the construction workers, they’ll block the street, they’ll block the whole thing.”

Nicaj said that while he has other stores to continue making an income, other businesses in the neighborhood might not be so lucky.

“Most local existing businesses that are here are going to end up closing down. I mean, not just me, but all these businesses around here. I’ve seen that happen in the Upper East Side,” he said, referring to the first phase of the Second Avenue subway project that opened in 2017.

Many East Harlem residents have acknowledged big changes are coming to their neighborhood, and Nicaj believed they’d be more sweeping than those seen on the wealthy Upper East Side following the first phase of the Second Avenue subway.

“I love Harlem. I’ve been here for a very long time. This is one of the true New York places still remaining from what New York used to be,” he said. “But you can get stuck in a time loop in the past … so you have to participate with everybody else.”

As MTA moves ahead with 2nd Avenue subway extension, East Harlem locals brace for change