Books on Black history, immigration found in trash by Staten Island school, sparking investigation

March 11, 2024, 5:01 a.m.

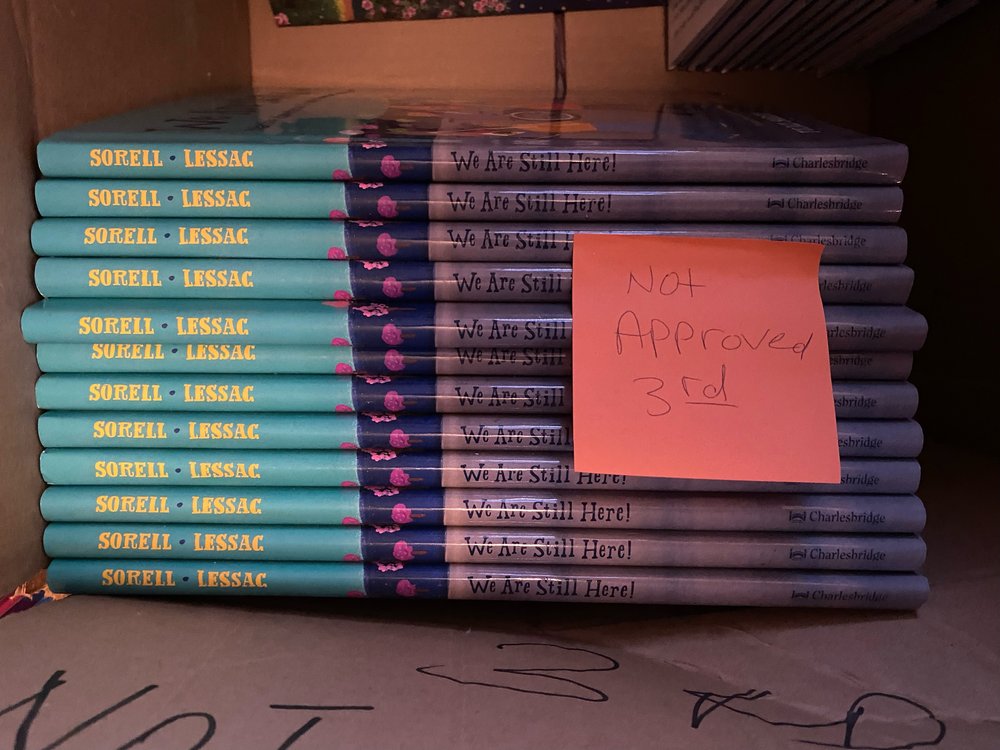

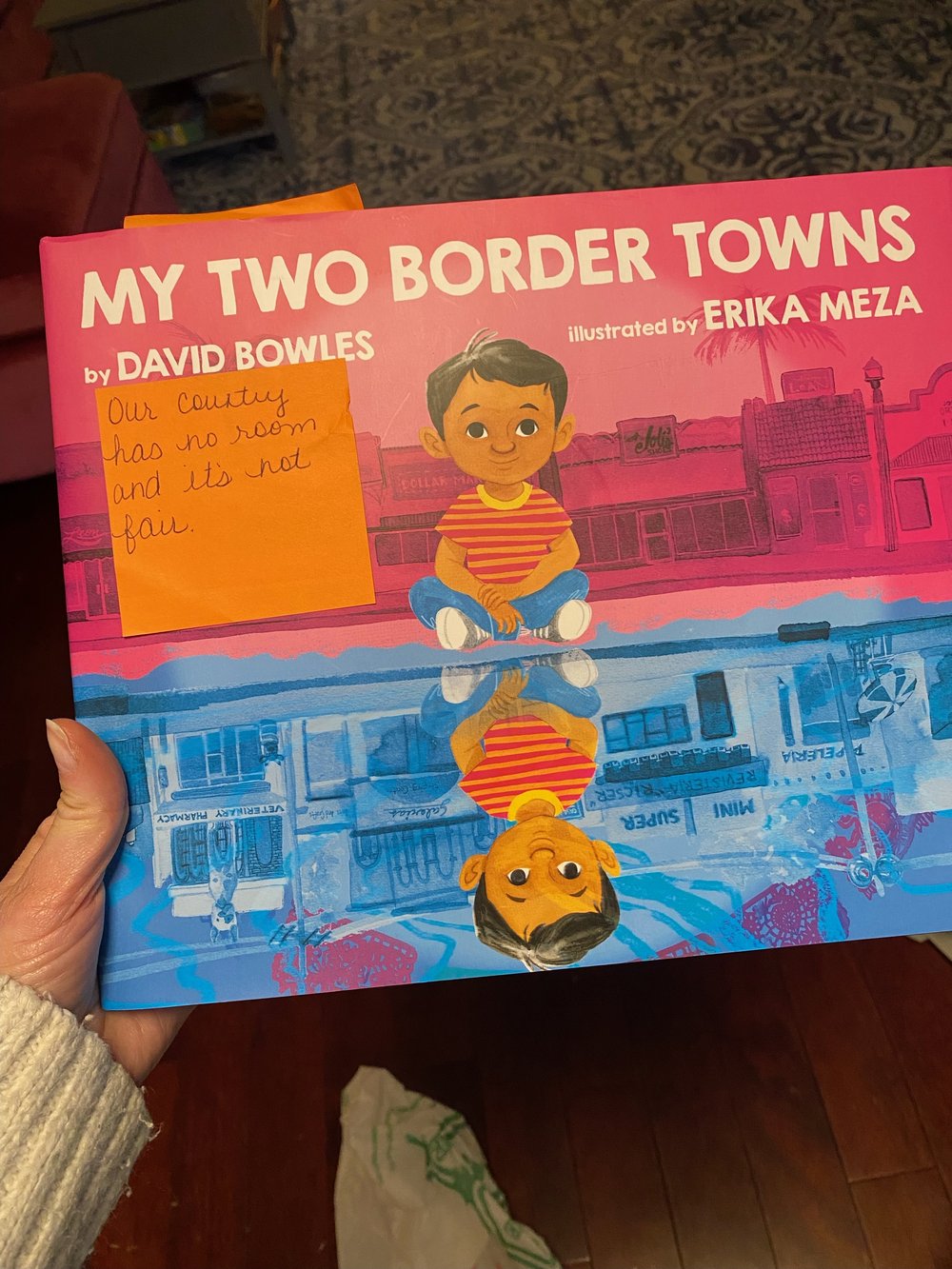

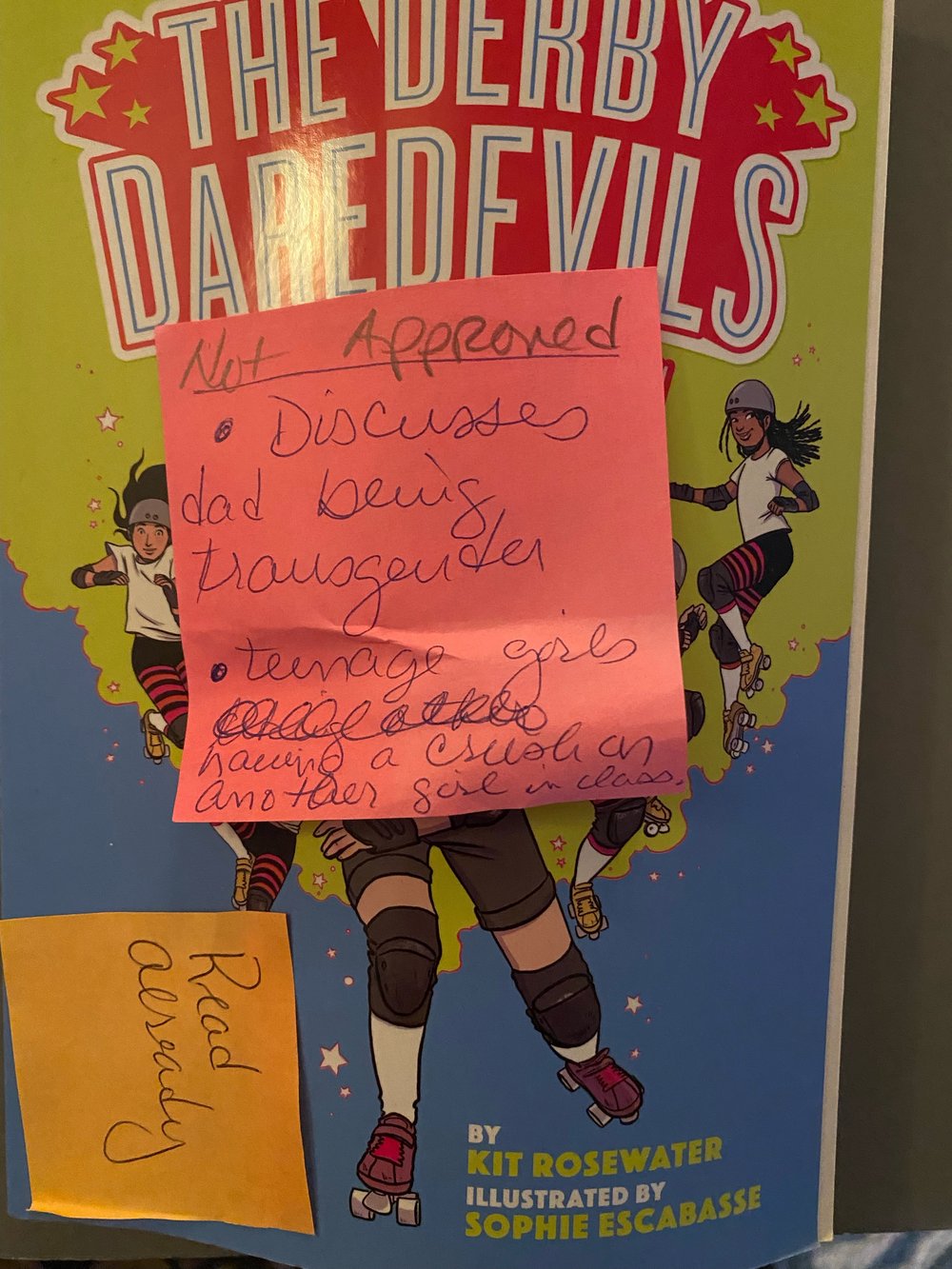

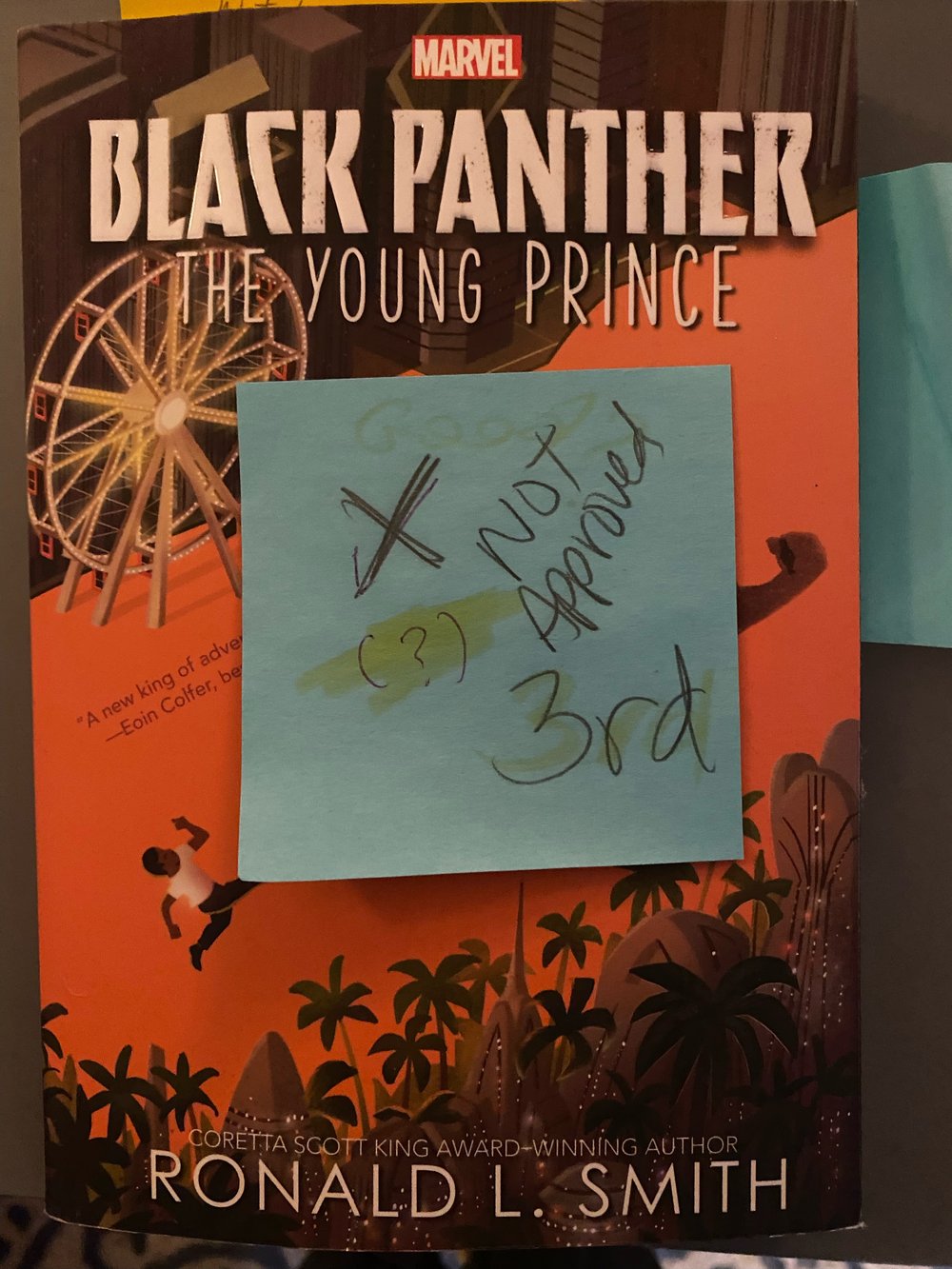

Sticky notes on the books discarded from the elementary school detailed apparent concerns about the contents.

Hundreds of new books featuring characters of color and LGBTQ+ themes were found by the trash at a Staten Island elementary school, outraging some parents and sparking an education department investigation.

Gothamist obtained photos from a Brooklyn book lover that showed boxes of kids’ books left with the garbage at PS 55, known as the Henry Boehm School. Some had sticky notes on them detailing themes and content in the books, which appeared to be part of a 2019 initiative to diversify school materials. The city education department launched an investigation after Gothamist shared the images.

A note on “My Two Border Towns,” about a boy’s life on the United States-Mexico border, read “Our country has no room and it’s not fair.” A note on “The Derby Daredevils,” about a girls’ roller derby team, read “Not approved. Discusses dad being transgender. Teenage girls having a crush on another girl in class.” And a note on “We Are Still Here! Native American Truths Everyone Should Know” read “negative slant on white people.”

Even books about the Marvel Comics hero Black Panther and legendary singer and activist Nina Simone were discarded.

It was unclear whether the removal of the books resulted from an objection raised by staff or parents. The education department said no formal challenge to the books was raised through official channels, though a part-time librarian had inquired about the process.

Until this incident, New York City had seemed largely immune from the high-profile efforts to ban books that are roiling school communities in Florida, New Jersey and other parts of the country.

“Our public schools do not shy away from books that teach students about the diverse people and communities that make up the fabric of our society,” education department spokesperson Nicole Brownstein said, noting the removal of the books was not sanctioned.

The school principal and PTA president did not respond to inquiries.

Many PS 55 parents were surprised to learn the books had been removed.

“I don't believe in banning books at all,” said Angela Hartje, whose daughter is in third grade.

“It’s one step closer to ‘Fahrenheit 451,’” she added, referencing the classic sci-fi novel by Ray Bradbury about a dystopian America where books have been outlawed.

'Not approved'

Holly Spiegel, of East Flatbush, alerted Gothamist to the controversy. Her neighbor, who was working near the school in November, retrieved hundreds of the books from the trash and gave them to Spiegel, knowing she could use them for the free “Little Libraries” she manages around their neighborhood. Spiegel then got in touch with the school and made two additional trips where she recovered hundreds more books in boxes marked “not approved.”

Sticky notes on the books pointed to apparent reasons why they were censored. A note on “Julian Is A Mermaid,” about a boy who dresses as a mermaid, read “Boy questions gender.” A post-it on “Chester Nez and the Unbreakable Code: A Navajo Code Talker’s Story,” cited a specific page, along with the question “white man’s world?”

Notes on pages of “Black Panther: The Young Prince” read “Witchcraft? Human skulls” and “Pact with Devil. Burned in fire.”

A note on “Nina: A Story of Nina Simone” read “This is about how black people were treated poorly but overcame it. (Can go both ways).”

“At its heart, this feels like censorship,” Spiegel said. “It feels like book banning.”

City statistics show the student body at PS 55 is 78% white, 11% Hispanic and 8% Asian. The teachers are 92% white.

Two parents at the school, located in Staten Island's Eltingville neighborhood, said they had heard rumblings about some controversy over books. But Gothamist was unable to confirm who led the effort that led to the books being tossed.

An unusual book battle

School controversies over books are rare in New York City. Since 2019, there have been only three challenges of books at other schools under an official protocol that involves the formation of a committee of parents, librarians, teachers and administrators, the education department confirmed. None of those books were removed.

“Should a parent feel concerned about the literature in their child’s classroom, they are encouraged to reach out to the teacher, principal, or superintendent,” said Brownstein, the department's spokesperson.

It’s more common for discussions in the city to focus on ensuring access to the materials. The Brooklyn Public Library runs a program where local students talk about controversial books with students in other parts of the country where they're actually being banned.

Alissa Barakakos, a PTA member at PS 55, said she was surprised that books about race, culture and sexuality had been removed — and that she would have opposed the effort if she’d known about it. She noted her son’s class just finished a series of discussions on Black History Month, and a unit on Native Americans.

“I don't know why the books would be thrown out,” Barakakos said. “I want my kid to be a part of the school community where everything is open and honest and kids are being educated.”

Spiegel said she was upset to see the books were kept from children. “The books aren't getting into the hands of kids who would identify with the characters, but they’re also not getting into the hands of kids whose worldview would be broadened by reading about people who aren't like them,” she said.

‘Mosaic’ problems

Some of the boxes Spiegel retrieved were labeled “Mosaic,” the name of a $200 million initiative launched late in the de Blasio administration to diversify school lessons and materials. An analysis by the New York City Coalition for Educational Justice found in 2019 that only 16% of elementary and middle school books were by authors of color.

De Blasio called for a total rethinking of the K-12 curriculum with an eye toward diversity. Mayor Eric Adams then scaled back the Mosaic plan, launching his own literacy initiative and supplementing lessons with materials reflecting LGBTQ+, Asian American and Black communities.

Thousands of Mosaic books were still sent to school and classroom libraries. But Natasha Capers, the director of the Coalition for Educational Justice, said schools received little guidance about what to do with the new books.

“They just were like, ‘here’s a big box of books,’” said Capers, whose group advocates for more equity in public schools.

She added that she was glad to know the books found with the garbage at PS 55 were "rescued.” But she said she was outraged to hear they had nearly been discarded.

“I watched my children throughout their schooling read so many books that used horrific language about Black people," Capers said. "There’s a book [that] used the N-word. You just had to suck it up because it’s part of the ‘canon.'"

She scoffed at the apparent discomfort with witchcraft and human skulls in the Black Panther book.

“You read Shakespeare, and ["Macbeth"] starts out with three witches around a cauldron,” she said. "Hamlet," she noted, “is legitimately talking to a skull.”

A 'teen council' at the Brooklyn Public Library combats book bans nationwide Student protest at education department headquarters will demand more Black history at NYC schools