As the migrant 'crisis' recedes in NYC, criticism of the city stands its ground

Oct. 16, 2024, 3:59 p.m.

"For New York City taxpayers, 60,000 is still 60,000 too many" migrants, one Republican lawmaker says.

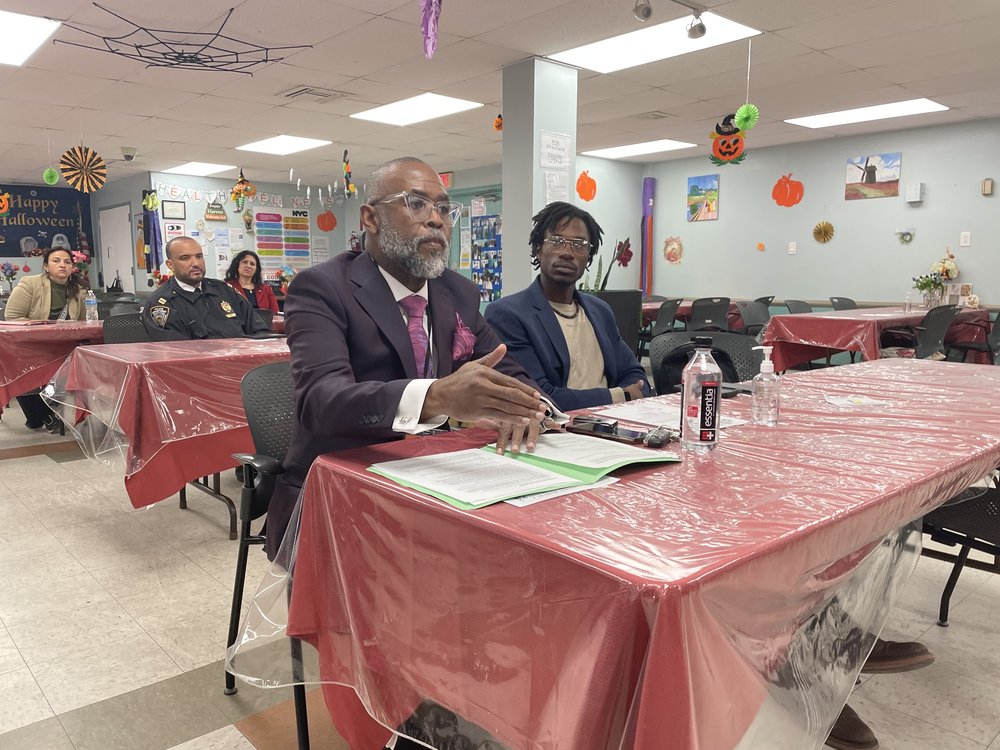

The Brooklyn Community Board 1 meeting was a sleepy affair, almost entirely populated by members of the board, city officials and police officers who were all on hand to discuss the state of the city’s migrant influx, which has long been described as a “crisis.”

But the extent to which residents of the district — which comprises Williamsburg and Greenpoint — are alarmed by the situation wasn't reflected in the meeting's attendance on Tuesday night: Just two residents showed up for an update from city officials.

Daniel Henry, director of external affairs at the Mayor’s Office of Asylum Seeker Operations, told the board that the worst of the migrant crisis was over. He said that 70% of the 218,000 migrants who had arrived in the city since spring 2022 had "moved forward on the next steps of their journey."

“It was more of a crisis in 2022," Henry added. "Now, it's more of a steady state.”

His words echoed Mayor Eric Adams' declaration on Oct. 9 that "we have turned the corner on this crisis." That statement came as Adams announced the closure of the 3,000-person Humanitarian Emergency Response and Relief Center for migrants on Randall’s Island. He said the closure, set for February, came after the city had experienced 14 consecutive weeks of declining migrant arrivals.

There are currently 60,000 migrants in the city’s care, according to city officials, down from a peak of 69,000 in January. Although Adams noted that the city is "not out of the woods yet," he said that "smart management strategies and successful advocacy" helped the city emerge from a difficult chapter.

But community members continue to express concerns about migrant shelters in their neighborhoods, as immigrant rights groups say the Adams administration needs to do a better job of getting migrants out of shelters and into more stable housing.

Some advocates also continue to call for the end of 30- and 60-day limits on migrants' stays in city shelters — an Adams initiative the mayor claims has helped reduce the number of migrants coming to New York.

Lloyd Feng, chair of Brooklyn Community Board 1's public safety and human services committee, said officers from the NYPD's 94th Precinct had informed the board of “moped-related robberies of retail establishments, individuals and cars,” while at a previous meeting “some committee members raised concerns about safety of the parks in Greenpoint and Williamsburg in the evening.”

Feng said there was little in the way of transparency from the Adams administration.

“CB1 residents deserve to know how many migrants live in shelters in the confines of CB1, where the shelter facilities are and how the shelter operators and city agencies have developed a concrete plan for community engagement,” said Feng.

City officials said 4,000 people were arriving in the city every week during the early days of the crisis in 2022. But that figure began to fall this year, partly because the Biden administration implemented a sweeping executive order early this summer that restricts who is allowed to apply for asylum at the United States' southern border. By late July, the number of weekly arrivals in the city fell below 1,000, and it currently hovers between 600 and 700, city officials said.

The declining numbers have not insulated the Adams administration from criticism over how it has handled the influx.

State Assemblymember Michael Reilly, a Staten Island Republican, said “for New York City taxpayers, 60,000 is still 60,000 too many” migrants in the city’s care.

“The strain that this places on our city services will have severe consequences, especially when we are already struggling to address homelessness, mental health and crime crises, and when some of our city's most vulnerable students are being denied their mandated services,” Reilly said.

City Councilmember Shahana Hanif, a Brooklyn Democrat who serves on the Council’s immigration committee, said the decline in weekly arrivals demanded a reconsideration of 30- and 60-day shelter stay limits for newcomers. She said the measures had proven to be “costly, counterproductive and a convenient excuse for [Adams'] austerity budgets.”

“As the pace of new arrivals to New York City slows and winter approaches, it’s time for the mayor and his administration to end these policies once and for all,” she said.

Murad Awawdeh, president and CEO of the nonprofit New York Immigration Coalition, argued that New York is likely to experience further “waves of migration” and that the administration should expand access to the CityFHEPS program or rental assistance vouchers so that anyone could qualify “regardless of immigration status.”

“It is time to implement policies that reduce the shelter population by enabling asylum-seekers to succeed,” said Awawdeh.

David Giffen, the executive director of Coalition for the Homeless, said that while the number of migrants in shelters is declining, "nobody is tracking what's happening to the families that are leaving the shelter system."

"So while we see the numbers going down,” Giffen said, “what we want to see is numbers going down because people are being helped, that are being helped into stability, that are being helped into housing, that are being helped to find jobs."

Kathryn Kliff, staff attorney at the nonprofit Legal Aid Society’s Homeless Rights Project, said the decline in the number of migrants in the city’s care provided more room for city officials to focus more on helping migrants with their legal predicament and permanent housing and less on the “front door," her term for immediate placement in emergency shelters.

“Since the beginning of this influx, we've been telling the city that they shouldn't only be focusing on the front door,” said Kliff, “because the more people they can help move out, the more space they would have had to begin with, and they wouldn't have had to be in such [a] crisis mode all the time.”

Camille Mackler, founder and executive director of the group Immigrant ARC, said that while the scale of new arrivals is currently waning, it is misguided to think “the moment is over.” Instead, she said, the city should invest in long-term solutions for the tens of thousands of migrants who are already here, while bracing for the next round.

“I think the most important point we have to remember is that people are going to continue to be on the move, and are going to continue to try to come to the U.S. and to New York,” said Mackler.

Randall's Island tent shelter for migrants will close at the end of February On Randall’s Island, a growing divide between sheltered migrants and neighbors Weekly migrant arrivals in NYC dip below 1,000 for the first time since 2022 Where did the migrants who left NYC’s shelter system go?