Albany Lawmakers Weigh A Ban On The Gay And Trans Panic Defense

May 30, 2019, 2:54 p.m.

The legislation would disqualify the discovery of someone's LGBTQ status as an extreme emotional disturbance, therefore prohibiting its use as a mitigating defense.

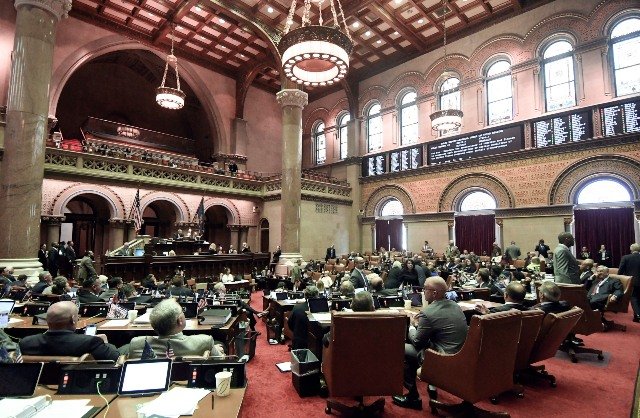

The State Assembly in Albany.

New York could become just the fifth state in the union to ban gay and trans panic defenses in court if legislation in Albany becomes law by the end of June. But as so often occurs, what would seem like legislation set to sail to easy passage in a state like New York may be undone by the typical bickering and dysfunction that define the Albany process.

The gay and trans panic defense is a court maneuver by those accused of murdering an LGBTQ person or by their attorneys, who claim to the jury that the victim’s sexual orientation or gender identity provoked the attack by causing “extreme emotional disturbance,” a recognized mitigating defense in the penal code, to the accused. If accepted by a court, the defendant’s murder charge could be reduced to a lesser manslaughter charge.

Governor Andrew Cuomo supports banning the legal defense and named it one of his top legislative priorities before the end of the session in a Tuesday radio interview with WAMC’s Alan Chartock. Prospective passage through the senate appears likely, with the bill being approved unanimously by the codes committee this month. The committee’s chair, previously an opponent of the measure, told Gothamist that the measure is more “timely” and that the defense needs to become a relic of history amid an upsurge in murders of trans people nationwide.

But two competing bills are sitting in the assembly’s codes committee, with different conceptions on how far to amend the state’s penal code to prevent the defense’s utilization.

“If the state recognizes that upon finding out that someone is gay or lesbian or transgender, and the state allows for the manslaughter charge, then technically the state is saying ‘we recognize that someone should be upset upon finding out someone’s gay or transgender or lesbian,’” said Assemblymember Brian Barnwell, the lead sponsor of one of the two assembly bills. “So they’re almost recognizing discrimination in a way.”

The legislation would disqualify the discovery of someone’s LGBTQ status as an extreme emotional disturbance, therefore prohibiting its use as a mitigating defense.

The phenomenon became well known as a result of the 1998 murder of Matthew Shepard, a gay man from Wyoming, when an attorney for Shepard’s killer unsuccessfully proffered the defense as an explanation for his actions. But while the taboo around using such a defense in court has made its practice a rarity, its subtle or explicit use has not been eliminated entirely.

As recently as last year, a Texas man was sentenced to just six months in prison despite fatally stabbing his neighbor for allegedly flirting with him; advocates accused his attorney of utilizing a gay panic defense.

In 2013, a transgender woman named Islan Nettles was beaten to death in Harlem by a man who later claimed he had flirted with her, but upon discovering she was trans began to beat her. Though the man was sentenced to 12 years in prison after pleading guilty, Nettles’s family argued that he should have received a lengthier federal hate crimes sentence, and that he and his representation had utilized a trans panic defense.

"Islan Nettles was brutally murdered in New York. Her murderer blamed his violent actions on Islan's identity as a transgender woman,” said D’Arcy Kemnitz, Executive Director of the National LGBT Bar Association, in a statement. “S3293 would prevent a similar situation from happening in New York's courts ever again."

If the bill were to pass and an attorney were to use the defense in court, a judge could declare a mistrial or the verdict could be reversed.

California became the first state to ban the defense in 2014, followed by Illinois, Rhode Island, and most recently Nevada. In New York, a measure to ban the practice has been introduced in several previous sessions but has always died, with the Republican-controlled senate refusing to consider it and assembly Democrats expressing concern over limiting the right to counsel.

But like so many other pieces of legislation, the unified Democratic state government presents a unique opportunity for the bill’s advocates.

“Now that we have the democratic majority, we passed GENDA and the ban on gay conversion therapy in the first two weeks of session,” said Senator Brad Hoylman, the bill’s sponsor in the senate. “So I’m hopeful that we can get this done in the senate.”

Indeed, Hoylman, in an interview with Gothamist, said that he sees sufficient support in the senate for the bill to pass, and that if anything, the issue would be in the assembly.

One of the bills, sponsored by Assemblymember Danny O’Donnell, would ban the use of the defense for second degree murder charges. The other, sponsored by Barnwell, would also ban it for first degree murder and aggravated murder charges. Hoylman carries both bills in the senate, but told Gothamist he prefers the O’Donnell version, which is more limited in scope.

"I will pass the bill that has the most viability in the assembly. I believe it is the O'Donnell version,” Hoylman said. “And I'm trying to figure that out over the next few weeks. I think we'll see passage in the senate by the end of session."

Nonetheless, the bill that passed the senate’s codes committee earlier this month was the companion to Barnwell’s bill, not O’Donnell’s.

O’Donnell, in an interview, called Barnwell’s bill “stupid” because both first degree murder and aggravated murder only apply in the penal code to the murder of police officers, firefighters, corrections officers, terrorism, and other specific offenses, while second degree is a more generalized murder charge; O’Donnell believes a gay or trans panic defense wouldn’t come into play in police killings, specifically.

Barnwell disagrees, specifically arguing that the penal code’s definition of first degree murder and aggravated murder do allow for gay and trans panic defenses to come into play, noting that first degree murder includes contract killing and defendants intentionally inflicting torture on their victims.

“If you’re recognizing it for one crime and not the other, that makes no sense,” Barnwell said. “You’re still recognizing then the fact that it’s reasonable.” Further, extreme emotional disturbance is listed as an affirmative defense for both first degree murder and aggravated murder.

Several factors undermine the bill’s swift passage, particularly the presence of competing bills and the rarity of the defense itself. If it is used, it’s often unsuccessful: in 1999, Jeremy Spaich, a Buffalo teenager who had murdered his male neighbor who had allegedly flirted with him, had the affirmative defense rejected by the appeals court, with his second degree murder charge sustained.

The bill may also run into problems in the assembly with members concerned by first and fourteenth amendment implications.

“Our house historically does not limit what lawyers can argue on behalf of their criminal defendants, because we are a body that is primarily concerned with the preservation of the right to counsel and preservation of the constitutional right to liberty,” O’Donnell said. “So those are problems.”

No explicit restrictions exist in the code on a defense attorney’s ability to argue on behalf of their client accused of homicide -- banning the panic defense would be the first time the legislature placed such restrictions on attorneys.

Last year, both houses rejected a push by Cuomo to include banning the defense in the state budget; Assemblymember Joe Lentol, the chair of the codes committee, told the New York Law Journal that both houses rejected the measure because of the limiting factor upon defenses at trial. But Lentol told Gothamist that, amid a nationwide surge in the murders of trans people, he would support passing the bill now despite his past reservations.

“Necessity is the mother of invention,” Lentol said. “So maybe there is a better way of doing this, I don’t know, rather than curtailing or limiting the use of the defense of extreme emotional disturbance like this. But I would like to see something done in cases like this, just because it seems to be timely right now that we should do something in order to curb these murders of people who happen to be gay or trans.”

Like Hoylman, Lentol said that he prefers O’Donnell’s more limited bill over Barnwell’s broader bill. A spokesperson for Cuomo, Jason Conwall, told Gothamist that the governor “supports both bills.”

The legislative session ends on June 19th, and as normally occurs, numerous high profile pieces of legislation are under consideration, perhaps most notably the renewal and reform of the state’s rent laws. As such, unpredictability and Albany dysfunction could also impede the legislation’s passage.

"I'm currently not optimistic about anything that happens in Albany,” O’Donnell said.