A look inside NYC’s ‘safe haven’ shelters, an alternative to sleeping in the streets and subway

Jan. 31, 2025, 6:01 a.m.

Mayor Adams is looking add more alternative shelter beds across the city and help keep the unsheltered from sleeping in the streets and subway.

Taneice Campbell said she was relieved when an outreach worker in an orange vest found her dozing in a subway car last December, shortly after she’d been evicted from her apartment in Queens. But she wasn’t necessarily eager to return to the shelter system.

“You don’t have too much privacy to get dressed,” Campbell said of the open, dormlike shelter she’d stayed in the last time she was homeless. “And sometimes, depending on the crowd, they just might want to take something.”

This time, the outreach worker helped Campbell, 47, get a spot in a 42-bed "safe haven" shelter in West Harlem, where residents either have their own rooms or just one roommate. That’s compared to a traditional shelter with more crowded accommodations, Campbell said. “You're safer, it's cleaner. People talk to you like family.”

As with other safe havens, rules at the Harlem facility, which is operated by the nonprofit The Bridge, are more relaxed than at typical shelters. It offers a more flexible intake process and eschews nightly curfews in favor of check-ins once every three days. It also offers a range of voluntary onsite services for clients, many of whom have mental illnesses or substance use issues. Because of these offerings, the city labels safe havens as "low-barrier" shelter options. Stabilization beds, which are similar but offer less-intensive services, also earn the title.

Mayor Eric Adams says he’s investing in a dramatic expansion of these city-funded, low-barrier beds, which currently represent a small but growing piece of the city’s sprawling shelter landscape. In his State of the City address earlier this month, the mayor vowed to add 900 safe haven and stabilization beds on top of the existing 4,000, as part of a broader $650 million plan to address homelessness and mental illness.

The low-barrier model is designed to entice people off the street by addressing the concerns that homeless New Yorkers often cite as reasons for leaving other facilities, including a lack of privacy — although, in practice, the number of roommates a safe haven resident might have can vary.

Adams and other city officials point to such low-barrier beds as key stops along a continuum that often begins with an encounter with city-funded outreach teams on the street or in the subway and ideally ends with housing. But data from the city and individual shelter providers show the model is not a silver bullet.

Getting people from safe havens into permanent housing can still be a lengthy, challenging process, and the majority of clients leave without a placement. Supportive housing, in particular, can create a bottleneck for safe haven clients seeking to leave.

Still, Molly Wasow Park, commissioner of the city’s Department of Social Services, said, “ Clients who are placed in safe havens typically stay inside longer and have a higher rate of connecting to permanent housing” than those placed in the broader city shelter system.

David Giffen, executive director of the Coalition for the Homeless, agreed with her assessment.

As the model expands, officials may also have to contend with pushback from some community members in neighborhoods where shelters are slated to open. One group of parents recently sued the city over plans to open a safe haven around the corner from an elementary school near South Street Seaport.

While city officials see “low-barrier” as a good thing, Peggy Bilse, a parent at the Peck Slip School, said it means shelter residents could have criminal histories, or “can be those New Yorkers that they say are the most vulnerable in terms of mental health issues, drug addiction issues.” She said she supports safe havens, just not so close to an elementary school.

“ I'm going to venture to guess that every one of those kids has had an interaction one way or another, even if it is stepping over somebody on the sidewalk who is experiencing unsheltered homelessness,” Wasow Park said. “Much better for everybody involved when people can be inside stabilizing their lives and have the support of staff, have security guards on site, all of those things.”

Some of the 900 beds Adams announced are already in the works and will begin coming online as soon as this summer, according to Wasow Park. She added that the city aims to find locations for the rest by the end of the year.

The city didn’t share a breakdown of how many beds were already planned at the time of Adams announcement, or which neighborhoods it’s targeting for new safe havens.

“ We've been really focused on siting safe havens in neighborhoods that have higher concentrations of those experiencing unsheltered homelessness and near end-of-line subway stations,” Wasow Park said.

The trajectory to housing

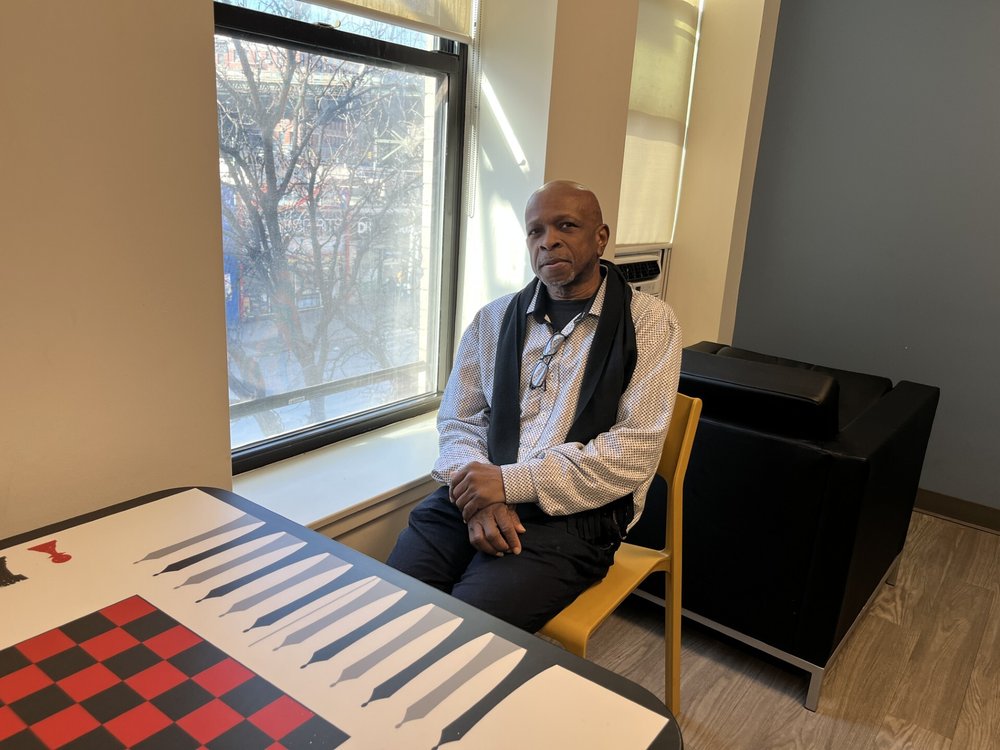

Kenneth Harris landed at the same safe haven as Campbell in late October, after an outreach worker noticed him wandering around Penn Station early one morning.

Harris, 60, has been homeless for over a decade, and before he was at a safe haven he had been staying “from place to place,” sometimes on a friend’s couch, sometimes in the subway. He said he’d become skeptical over the years of promises of permanent housing.

After just three months at the safe haven, he will use city rental assistance to move into his own apartment in the Bronx in February. He said he’s most excited to have his children and grandchild come visit.

“This helps with making a connection with them again, or strengthening the connection,” Harris said. “Now they can come and be with me at times, you know? Instead of having to wonder where I'm at.”

While the process of finding housing can take just a few months for some, the trajectory for others isn't as seamless. Safe haven staff have to help clients dealing with a range of complicated life circumstances navigate the city’s subsidized housing bureaucracy.

Overall, about 28% of clients who exited the city’s safe haven or stabilization beds in fiscal year 2022 were headed to permanent, subsidized housing, according to a report from the city comptroller. The city Department of Social Services did not respond to requests for more recent data.

Many safe haven clients qualify for supportive housing, which comes with its own set of social services and is primarily reserved for people with mental health and substance use issues. But citywide, the wait for a supportive housing spot can take more than a year — and people can be rejected by individual supportive housing operators for a wide range of reasons.

Over the last fiscal year, 660 safe haven residents were deemed eligible for supportive housing, but just 249, or 38% of those who qualified, were actually accepted into supportive housing programs, according to city data. In many cases, the supportive housing provider simply filled the vacancy with a competing applicant. In others, they said they couldn’t offer the medication monitoring or other care the person required.

Wasow Park acknowledged that supportive housing is a scarce resource, and that many providers and funders have their own unique requirements, which can impede placements. But she noted that the city is working to add more units, including about 1,000 last fiscal year.

Some safe haven clients qualify for rental assistance, rather than supportive housing. In Campbell’s case, she said part of why she’s been at the safe haven so long is that she had lost many of the documents the staff needed to help her get approved for a voucher. With the voucher now secured, she said she is looking at apartments — including one that she said had to undergo “ extensive work” to pass inspection before she could move in.

Where do people go?

The two safe havens operated by The Bridge in Harlem and the Bronx discharged a total of 134 clients over the past year, with 30 going to permanent housing, or 22%, according to the nonprofit.

Some who leave without a placement go into a rehab facility or get reunited with family, said Lisa Green, The Bridge’s chief program officer for residential services.

But clients also go back to the streets for various reasons, according to staffers at The Bridge and another safe haven provider, Breaking Ground.

“ Sometimes they are having interpersonal conflicts with other residents or things like that and so they'll get fed up and want to have more space,” said Erin Madden, vice president of programs at Breaking Ground. “Living in a communal situation, for any adult, is hard.”

Both Breaking Ground and The Bridge said they work with outreach teams to try to bring people back in if they leave for more than 72 hours.

Giffen of Coalition for the Homeless said there should be more “housing first” programs that don’t require people to be funneled through temporary placements before they're offered permanent housing — a position that city comptroller and mayoral candidate Brad Lander recently espoused. But both acknowledged that even if there are more “housing first” options, some people might still benefit from safe havens.

Giffen argued the city should scale up the number of low-barrier beds even more rapidly. “ There are a lot of people in the congregate shelter system as a whole that, frankly, should be in safe havens,” he added.

The Bridge is already planning its next safe haven for Webster Avenue in the Bronx, which Green says will be the first in the city to specifically cater to LGBTQ+ residents.

“ Often, LGBTQ+ individuals are placed into either an all-male or an all-female setting and they face some discrimination from other clients and it's tense,” she said.

That safe haven will likely be able to start accepting clients by August.

Homelessness, mental health and subway safety: How Hochul and Adams faced the trifecta in NY More 911 mental health calls are going to an NYPD alternative, but police still handle most NYC unveils new option for homeless people discharged from psychiatric hospitals As city clears homeless encampments, questions surround Adams' plans for new shelter beds