How friends built the Red Hook Pinball Museum, with some machines dating to the 1880s

Aug. 16, 2025, 8:01 a.m.

It's one of the only playable collections of electromechanical pinball machines in New York City.

On a recent Sunday in the back room of Seaborne, the Red Hook cocktail bar, Wesley Michalski was balanced atop several crates of tonic water, elbow-deep in the back of a 1964 Gottlieb “Majorettes” pinball machine that had just glitched, mid-play.

“The ball count stepper unit, which keeps track of what ball you’re on, snapped off completely,” Michalski said this week, recalling the emergency repair. “We couldn’t pull [the pinball machine] all the way out because there were 20 people in here, so I’m leaning over the back and managed to make it work again.”

“It still has a slight hiccup, sometimes it gives you four balls instead of five when you reset it,” Michalski said. “So for our tournament on Saturday, we got to make sure we’re dialed in.”

Michalski is co-founder of the Red Hook Pinball Museum, an unlikely and endearing addition to the neighborhood’s patchwork of niche passions and DIY institutions.

Opened in February, the museum houses one of the only playable collections of electromechanical pinball machines in New York City, with some models going as far back as the 1880s. On Saturday, the museum is hosting a pinball tournament beginning at 2 p.m.

The passion project belongs to Michalski and his friend and co-founder Kevin Murray, both musicians in their 20s. They’ve spent thousands of hours restoring these analog marvels.

Most casual pinball players are more familiar with flashy 1990s-era games like Twilight Zone or the Addams Family, Michalski said. But the museum’s machines hail from an earlier analog era.

Unlike the movie-branded games common in arcades and bars today, the Red Hook collection features original designs for games like the cheerleader-themed “Majorettes” and “Diamond Jack,” a classic card-themed machine from 1967.

These games don’t talk, play music, or flash LED screens; instead, they rely entirely on chimes, bells, score reels and gravity.

These types of machines are rarely played outside of classic pinball tournaments, Michalski said, making him and Murray usually the youngest enthusiasts in the room by decades.

“Everything in these machines runs on electromagnets,” Murray chimed in. “It’s a very physical experience when you’re playing, you can actually feel the mechanisms operating. In the case of digital games, you don’t — they feel eerily silent when stuff happens.”

The duo favors “Add-a-Ball” machines, a type of pinball game that awarded players extra balls instead of free replays — a workaround developed to skirt then-Mayor Fiorello La Guardia’s 1942 pinball ban, which treated replays as a form of gambling, and therefore illegal.

The ban remained in place until 1976, when pinball historian Roger Sharpe famously demonstrated to the City Council that the game was one of skill, not chance.

Michalski and Murray bring the games back to life through hours of sanding, wiring, troubleshooting and parts-scavenging, often sourcing on Facebook Marketplace, and improvising some repairs with parts they make themselves.

Each machine is paired with a handmade placard explaining its rules, quirks and historical backstory. The space is strung with red bunting and the cabinets are dressed with skirts handmade by a friend of the museum, in a nod to old arcade aesthetics.

The museum hosts an open house every second Sunday of the month, along with occasional tournaments that draw a mix of local families as well as competitive players from across the region.

“It’s normally a bunch of families, all these kids standing on milk crates playing pinball,” Murray said. “One in particular was so sweet — him and his mom came and she said ‘Yeah, he loves pinball, so we bring our own stool so we can go play at different places.’”

“Kids really love them because there’s not quite as much of a skill element [as newer digital games],” Michalski said. “So you’re not as hard on yourself if you’re not doing so well. You know it’s not your fault.”

A whiteboard posted near the bar keeps a running tally of all-time high scores — a rotating honor mostly shared between “KM” and “WM” for now.

Getting the machines to Red Hook has sometimes required extraordinary effort. While chasing one rare machine, the duo woke up at 3:30 a.m. to rent a minivan and drive 27 hours to Ontario and back, stopping only to double-park outside Niagara Falls for a 30-second glimpse before security waved them along.

The museum came about via an informal arrangement with Lucinda Sterling, Seaborne’s owner and a veteran of New York’s craft cocktail scene. Sterling had pinball machines in the back of the bar years earlier, so when the founders approached her about storing and restoring a few games in the back, she agreed.

Over time, their fascination with older machines grew into a mission: They didn't just want to share them, but also wanted to tell the story of pinball's evolution and survival.

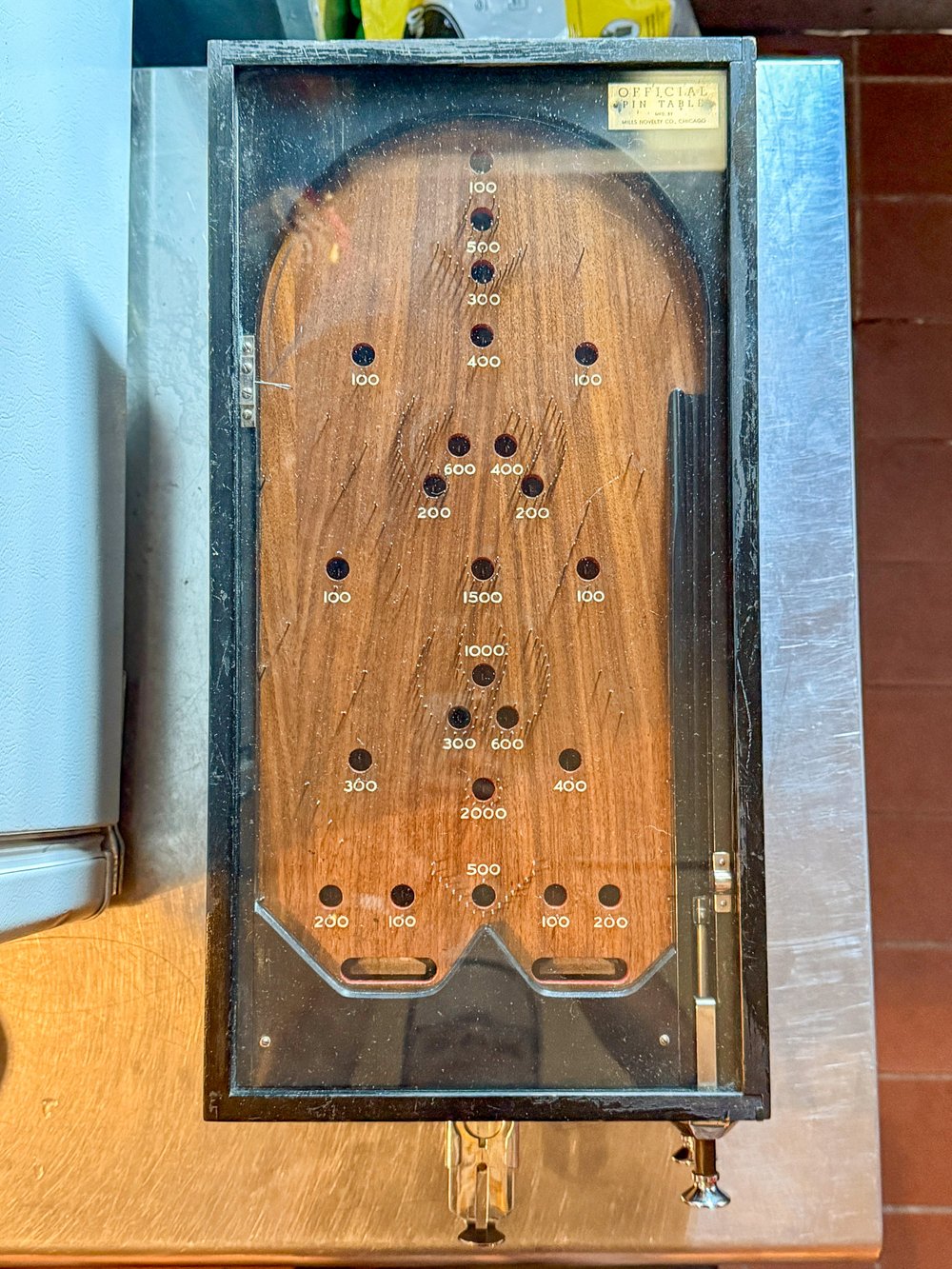

The museum features playable machines as early as 1931’s “Whiffle,” which many consider to be the first true pinball machine. Nearby sits an 1880s wooden Bagatelle board, a pinball predecessor which used a pool cue rather than a plunger to manually shoot the ball.

“The one here at the museum is maybe two-and-a-half feet long, but these would be five, six-foot tables, often in aristocratic French circles where they’re playing their fancy parlor games,” Murray said.

Visitors can drop in by appointment, or during the public open houses or tournaments. All the games are free to play, though the founders encourage donations. The pair said they are in advanced talks for a second location in Carroll Gardens, and weighing nonprofit status to ensure the collection’s future.

This post has been updated to correct the spelling of Wesley Michalski.

Red Hook public pool planned to reopen Sunday after broken pipe caused delays all summer Bojangles is coming back to NYC, starting in Brooklyn