Columbia suspended him after he built a cheating app. Now he’s raised $5.3M for it.

May 2, 2025, 6 a.m.

“The future where we use AI more and more is inevitable,” said founder Roy Lee. “Everyone is going to be uncomfortable with it, but it’s better that we embrace the discomfort.”

A Columbia University undergrad who was suspended for building an artificial intelligence tool to cheat on coding interviews at tech firms has raised $5.3 million to turn the idea into a company with much bigger ambitions.

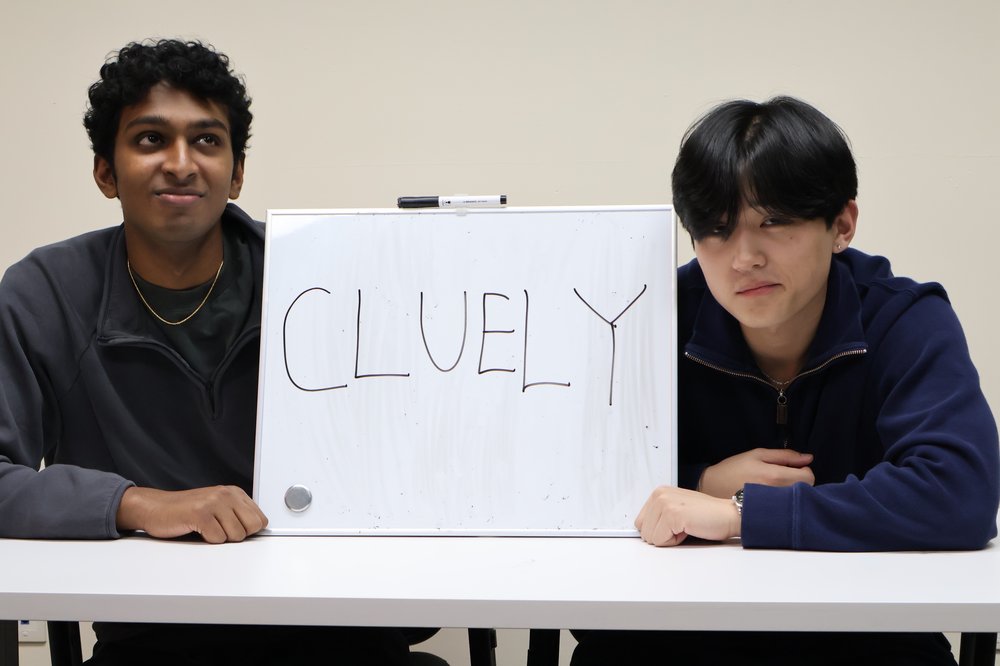

Co-founder and CEO Roy Lee, 21, announced the funding on LinkedIn on Sunday. Previously known as Interview Coder, the company is now called Cluely, with a manifesto about using generative AI to “cheat on everything.”

For a $20 monthly subscription, Cluely’s paid version provides a real-time AI assistant that watches and listens in on virtual conversations like job interviews, sales calls and meetings, offering real-time prompts, suggestions and analysis. The desktop application promises to bypass tools set up to detect that it’s running.

The “cheat on everything” tagline is more marketing than mission, Lee said in a phone interview.

“You can’t really cheat on a conversation,” Lee said. “It’s just meant to be provocative. The future where we use AI more and more is inevitable. Everyone is going to be uncomfortable with it, but it’s better that we embrace the discomfort.”

Cluely’s story taps into a growing conversation about how generative AI is reshaping what it means to work, learn, and communicate, as well as how institutions are being forced to grapple with new technology.

‘Prepare them for the world that’s coming’

Lee said he didn’t know a single undergrad at Columbia who hadn’t used AI on an assignment.

“Some of the professors are like the only voices against it, but I would not be surprised if something like 99% of undergraduates use AI when they’re not allowed to,” he said.

The school’s website has a 2,800 word AI policy it describes as a “work in progress,” which encourages exploring generative AI tools but prohibits their use in exams or assignments without the instructor's explicit permission. The policy promises to include a list of approved tools and usage scenarios, but does not say when it will do so. Columbia did not respond to a request for comment.

For Lee, going viral was always part of his plan. During the fall 2024 semester, he and his co-founder and then-classmate Neel Shanmugam decided to garner attention by making something provocative.

They built a tool called Interview Coder to help users cheat on “LeetCode”-style technical interviews – the widespread coding and quantitative problems that many tech firms use as a hiring screen for engineers. Much like modern university exams taken on a computer, technical interview problem-solving sessions are often monitored through proctoring tools that record all computer activity to make sure no outside help is being used.

They filmed themselves using the tool to land internship offers from companies like Meta and Amazon. After they posted one of the videos publicly and Amazon complained to the school, Columbia suspended Lee for violating university policies. His story went viral in tech circles after he tweeted about the experience in late March.

Having effectively seized the industry’s attention, Lee and Shanmugam dropped out to focus on building the company, which expanded in scope from an AI tool for prospective tech engineers to an AI tool that helps you “cheat on everything.” Within weeks, they raised $5.3 million from two established Silicon Valley venture capital firms, Abstract Ventures and Susa Ventures.

Lee used the example of a sales agent researching a prospect, learning details of their personal and professional life in order to make a more effective pitch. Using AI to do that research during a call may strike people as deceptive, but is not fundamentally different from doing it before the call, he argued. He compared Cluely to calculators and spellcheck: tools once derided as “cheat codes" that would short-circuit organic knowledge, but have become part of everyday literacy.

“People would say, you can’t rely on a calculator, you’re never going to have a calculator in your back pocket,” Lee said. “Now everyone literally has a calculator in their back pocket.”

With its funding secured, the start-up is hiring – and Lee said his own interviews are designed to be AI-proof. He doesn’t see any irony here: The whole point he was making with “Interview Coder” was that technical tests, which can be easily gamed with an AI tool, are simply wasting everyone’s time.

He encourages candidates to use any AI tools they like during the interviews, and talk through their process.

“If you’re coding something and you hit a bug, there’s a programmer that will throw it into ChatGPT and say ‘fix this bug,’ and there’s a programmer that will say, ‘You’re calling two hooks inside a use effect which shouldn’t be there, help me debug this,’” Lee said. “It’s very simple to vibe check if someone knows what they’re doing or is just mindlessly prompting, fingers crossed.”

Lee maintains that Columbia mishandled his situation.

“It’s crazy to me that they’re not the first people to openly embrace the use of AI,” Lee said. “If you’re truly raising the future leaders of tomorrow then it’s only natural that you prepare them for the world that’s coming. And that’s not a world where we have more and more banning of the technology that exists.”

Cluely is too new to have widespread reviews, though Lee posted screenshots suggesting some 3,600 users were paying for InterviewCoder in March, before his story went fully viral. Journalists testing Cluely have reported the same type of glitchy and inaccurate behavior as many generative AI technologies, with tech publication the Verge writing “it didn’t help me cheat on anything.”

‘The horse has left the barn’

A recent University of Pennsylvania study asked dozens of students in undergraduate and graduate programs how they use AI, conducting interviews in Spring 2023 and repeating them this semester. It found students using generative AI for everything from crafting emails and cover letters, writing essays, conducting research, lowering language barriers for foreign students and more.

“It’s changed a lot,” said Ross Aikins, the professor in the graduate school of education who leads the study. “Say you have two sections of the same class, with an AI evangelist teaching one section and a prohibitionist teaching the other – students overwhelmingly prefer the person who’s embracing AI because they think these skills are going to be very useful in not just the classroom, but their future careers.”

Aikins said “the horse has left the barn” in terms of AI adoption among the student body. He said it's up to universities to adapt and develop learning and assessment tools that challenge students to demonstrate the value they add on top of AI.

Anand Rao, who chairs the communications department at the University of Mary Washington, a public liberal arts school in Virginia, is actively developing an AI curriculum and already offers a free one-credit “Intro to AI” course.

Rao is a staunch advocate of integrating AI tools in the classroom rather than banning them, and believes students should learn to use AI tools thoughtfully and responsibly.

Rao sees AI as a disruption that brings back the need for humanities and liberal arts skills. “For the last couple decades people have shied away and said those aren’t as important, you need technical skills. Well, now it’s a little different,” he said.

Rao said “soft” skills of leadership, communication and collaborative critical thinking are even more important for students who will one day direct AI agents and tools in the workplace.

In his argumentation and debate class, he encourages the students to use AI not only for research, but to engage in mock live debates and sharpen their own skills and arguments.

He acknowledges that designing courses that embrace the technology is challenging.

“I’m very sympathetic to colleagues that have used assignments and experiences in the classroom that have been tried and true over the years that just aren’t gonna work as well now,” Rao said.

Lee, the Cluely founder, said it’s impossible to know, but he likely wouldn’t have finished at Columbia even if he weren’t suspended, as he was primarily focused on building the company.

He also has to thank the school. Without the virality that Columbia’s suspension provided, his company may not have raised its $5.3 million so easily.

Is a Jalapeño Sauvignon Blanc the drink of the summer? New Yorkers weigh in. Is it possible to be a working-class artist in NYC anymore?