After 41 years in Tribeca, NYC’s iconic neon studio is relocating to Sunset Park

June 3, 2025, 2:16 p.m.

“As much as it’s sad to leave the neighborhood, it’s exciting to go to Brooklyn,” Let There Be Neon's new owner says.

Let There Be Neon, the decades-old custom neon studio that helped light up Studio 54, the Chelsea Hotel, Russ & Daughters and generations of New York City storefronts, is preparing to leave its Tribeca home this summer.

After more than half a century downtown, the studio will relocate to Sunset Park, trading a now-pricey retail frontage for more space and fewer walk-ins.

The move, which was first reported by Tribeca Citizen, marks the end of a chapter for one of New York’s most distinctive creative institutions and for a neighborhood whose industrial soul has long since faded.

“Let There Be Neon is a New York institution,” said sign maker David Barnett, cofounder of Noble Signs and the New York Sign Museum. “They wrote the book on neon.”

That's literally true: Copies of founder Rudi Stern’s 1979 book “Let There be Neon” sell for more than $100 online.

For new or old fans of the glowing storefront, there’s still time for a final visit before the move, which will happen by the end of summer, according to longtime owner Jeff Friedman.

“As much as it’s sad to leave the neighborhood, it’s exciting to go to Brooklyn,” said Dave Waller, who is taking over Let There Be Neon as Friedman retires, and who owns the 91-year-old Boston studio Neon Williams.

“A lot of creative people live and work there already. ... In time, people will find us in the new location,” said Waller.

'It dazzles you'

The first neon lighting was unveiled in Paris in 1910, some 12 years after the noble gas was first extracted from earth’s atmosphere. Neon signs were introduced in the United States in the 1920s and peaked in the mid-1930s to 1950s before declining in popularity, according to the Neon Museum.

Stern, a multimedia provocateur who designed psychedelic light shows for Timothy Leary and made neon works for John Lennon and Yoko Ono, Bloomingdale’s, Time magazine and more, founded Let There Be Neon in 1972. He believed that neon, which was often dismissed as “visual pollution” at the time, was a disappearing American folk art that was worth preserving.

From its original SoHo gallery, Let There Be Neon offered both custom light art and restorations of vintage signage, treating everything from pizza shop signs to avant-garde installations for artists like Doug Wheeler and Nam June Paik with the same artistic reverence.

“When people think about the beauty of 20th century signage, they’re thinking about neon,” Barnett said. “It dazzles you.”

Stern’s vision helped spark a neon revival in New York, and Friedman, a one-time employee who later became Stern’s business partner, carried the mission forward. And while Let There Be Neon is best known for the classic signs it’s restored, including the iconic glowing harp outside Dublin House on the Upper West Side, or Katz’s Deli, or the White Horse Tavern, Friedman said the vast majority of its work glows quietly inside restaurants, galleries and private homes.

Neon’s survival isn’t just a matter of taste but a question of economics. In recent years, cheaper LED lighting has become a popular alternative, leading many businesses to scrap their glowing glass signs. And half the world’s neon was produced in Ukraine until the Russian invasion disrupted that supply, leading prices and usage to fluctuate wildly.

In December, Tishman Speyer received approval from the Landmarks Preservation Commission to replace Rockefeller Center's neon signage with LED. The Apollo Theater in Harlem made a similar switch.

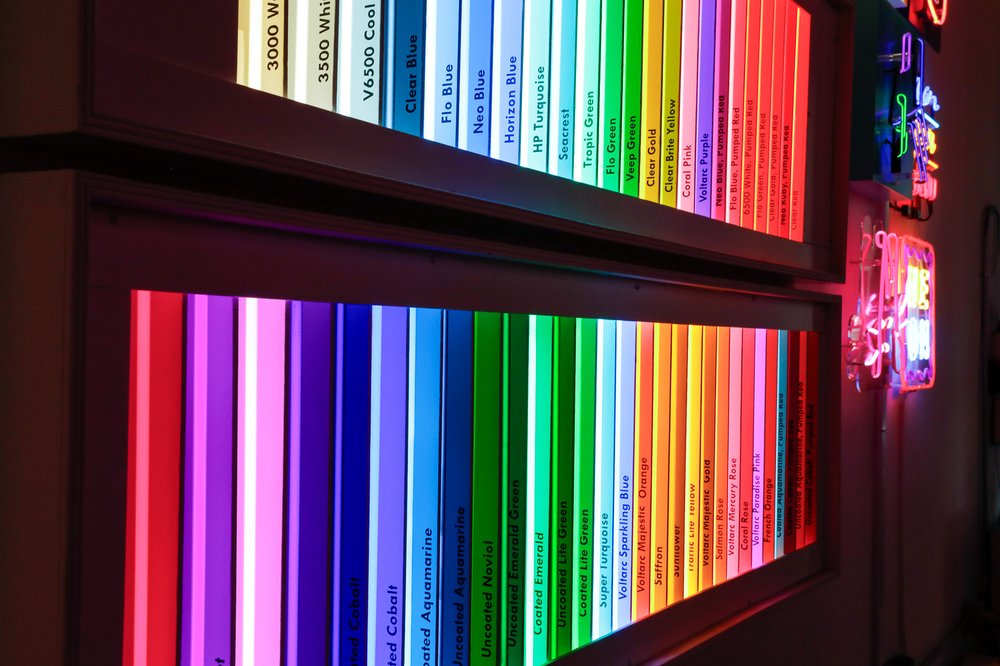

Let There Be Neon’s continued presence in the city pushes back against that erosion. The studio still bends glass by hand, charges gas into tubes and restores signs that might otherwise end up in a dumpster.

In an age when commercial signage may be disposable, the studio's work is built to last. Friedman said a customer came in recently complaining about a neon sign that broke; it had been working since 1975.

The workshop’s departure underscores how much Tribeca has changed, Friedman said. When it first opened, it was part of an entire design industry district, with makers like the erstwhile Industrial Plastics. There were few restaurants, no designer boutiques and hardly a pedestrian in sight.

“This was the fabric district, and SoHo was the paper district,” Friedman said. “When I worked for Rudi, there was a staples store across the street — and I mean a guy who made staples. Not Staples, the office supply.”

Now Canal Plastics and Canal Rubber are some of the last holdouts from a time when clusters of manufacturers made the area a one-stop haven for art, craft and design. Friedman said continued to benefit from its location as that fade, until the pandemic disrupted in-person work.

“For me, the neighborhood really started to change a long time ago,” Friedman said. “Our neighbors now, with very few exceptions, own really expensive loft spaces.”

“I always joke that when we first moved in [in 1984] we were on the outskirts of Chinatown,” he said. “Now we’re in Tribeca — and we haven’t moved.”

The shop’s few longtime neighbors are mourning its departure — one woman stood in the doorway and cried, Friedman said. And he’ll miss hosting school groups, where kids are always thrilled by the alchemy of neon gas, flames and bent glass.

“There’s something bittersweet about it,” Barnett, of Noble Signs, said. “It’s an iconic storefront. … You’ll walk down White Street and go ‘Oh yeah, that’s where Let There Be Neon used to be.' But it’s very good to hear they’re staying in New York City.”

Meet the family that's been delighting Queens diners for almost 50 years How the West Village's Henrietta Hudson thrives as other lesbian bars shutter