A new documentary looks at Supreme and the rise of NYC’s skateboarding scene

July 13, 2025, 9:01 a.m.

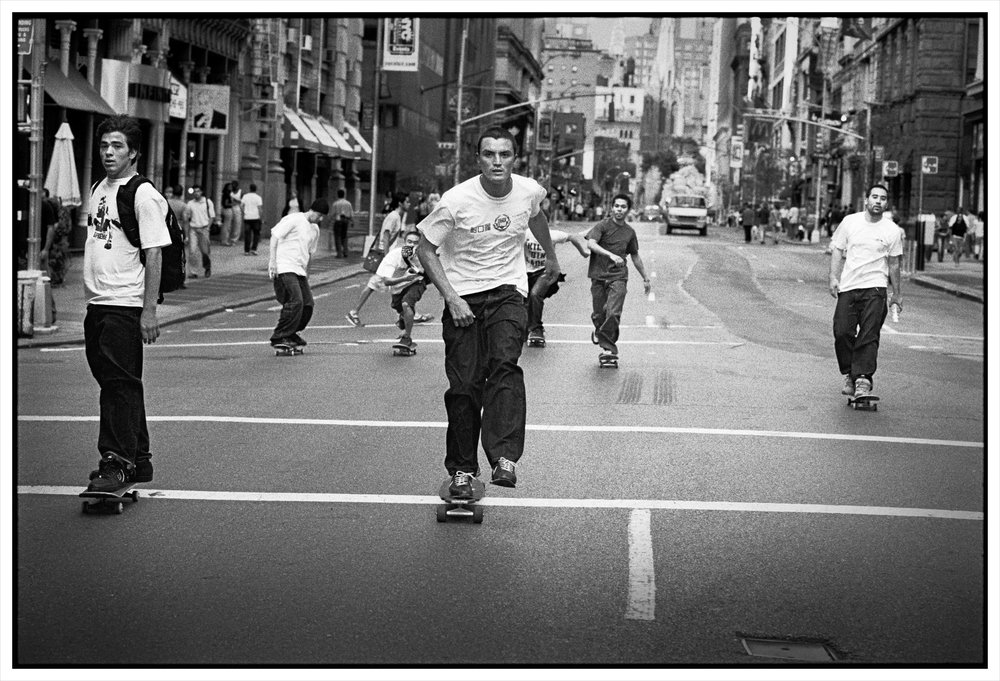

The city’s original influencers were its ‘90’s skateboarders.

Before Supreme was a global fashion giant with lines around the block, it was a small, one-of-a-kind shop on Lafayette Street that was popular with early 1990s skateboarders and known for being hostile to customers.

Now a new documentary, “Empire Skate,” looks at the history of the city’s skateboarding scene and the rise of the brand Supreme and its influence on global culture.

“I thought we'd run into some people who were bitter about how big it got and had a lot of negative feelings towards just the exploitation of this little tiny shop that they made cool,” said director Josh Swade.

"Really, everyone is just so celebratory and so complimentary about what Supreme meant to them and what it still means to them, that it was really heartwarming," Swade said.

Using archival footage, Swade captures the attitude that was unapologetically New York City. As skateboarding moved from underground into the streets and gained mainstream acceptance, Supreme grew from a local skate shop into a fashion icon, pushing streetwear into the spotlight.

Alison Stewart caught up with Swade on an episode of “All of It” to discuss the rise of Supreme and skateboarding culture. Below is an edited version of their conversation.

Alison Stewart: What did you learn about the history of New York skateboarding that flew in the face of common knowledge?

Josh Swade: Kids in this city didn't have space and they didn't have what they had in Southern California, which was ground zero for skateboarding. They had to be improvisational, but also have a lot of courage, because they were doing things in the street that took a lot of fearlessness.

For a New York brand of skate to evolve over time meant that these were kids that were standing on the shoulders of other kids, who were attacking the pavement, the curbs, a park bench, and a ledge in ways that was just dangerous, and very much to the spirit and attitude of New York City.

When did you know which way the story was going to go? That it was going to wind up at Supreme?

Very early on, that was just sort of the meeting place and the clubhouse for these guys, where they got together and decided where to go skate, and just where they came back to after a hard day of skating, it was home.

If this place is home, that becomes the hook, the narrative through-line. The place from which this culture builds. Really, really early on, we discovered that there was no way to tell this story without the shop.

One of the things that makes this documentary so worth watching is all of the archival footage. Where did this archival footage come from?

It’s fortunate for someone who's trying to make a film, because skaters, in a lot of ways, were trailblazers. They had cameras, the sort of camera you could walk into, say, a Best Buy, or — New Yorkers will certainly remember The Wiz, back in the day — spend a few hundred bucks and get a camera, and then follow your friends around as they try and do their tricks.

The beauty of it is, those cameras oftentimes stay on past the day of skateboarding. They stay on when they're hanging out, when they're having their downtime. It gives you just this richness and this gold mine of a time and a place that really speaks to skaters in particular, because they had cameras.

When you think about it, they were the original content creators.

That's right. They were ahead of their time and they were filming everything.

The underground skate scene in the city offered a belonging for kids from some pretty rough backgrounds. How much of this was about self-expression on the board and how much of it was about their survival as human beings?

As we, I think, do a good job in the film of showing the audience, skateboarding, for them, was like the ultimate release. You're right. Most of them, if not all of them, came from really difficult home situations, broken homes, abusive parents. Many were latchkey kids and they had no control over the circumstances they were born into. Yet, once they got on the board, a real sense of freedom drove them, and that happiness that came from riding became an escape.

That's a story that's pretty bespoke to New York City: Skating was the ultimate ticket to go wherever you want. You don't have to be stuck in your home in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. You can go to Manhattan, find your crew, and together, you guys can go explore.

It creates a bond, it creates family, and yes, the self expression comes as they get better, hone their skills, and find the thing that makes each one of them an artist and an athlete. Skaters are really both of those things. They're artists and athletes all at once.

I want to talk about the community that came up around these community clubhouses, where the kids, the young skaters, were going. They were small and they were mighty. They were skate shops. Why were they so important to the community?

I think in a lot of ways, they were looked at in the beginning as nuisances. They were in people's way. They were scaring folks walking down the street. This wasn't a city that had welcomed this activity with open arms, to put it mildly. They were really, really outcasts in this city. Our story shows that history.

You get to the end, in modern times, and the city has done an unbelievable job changing its attitude towards this sport and this pastime, with skate parks now littering our five boroughs. It's beautiful and amazing to see, but it wasn't always like that.

Yes, you have a lot of the OG skaters in the film: Jefferson Pang, Ryan Hickey, Javier Nunez. Was there anything that they told you that surprised you about their experience?

I think that their allegiance to the brand and the shop. All these years later. It opened in 1994, and here we are, 31 years later, and I thought we'd run into some people who were bitter about how big it got and had a lot of negative feelings towards the exploitation of this little tiny shop that they made cool, that they called home.

Really, everyone is just so celebratory and so complimentary about what Supreme meant to them and what it still means to them.

We've gotten to 1993, 1994. There's sort of a resurgence around skateboarding. It's got a new energy. One person, James Jebbia, saw an opportunity.

He transformed the skate clubhouse to a retail space under the heading Supreme. What was the original business strategy and what was different about Supreme?

Well, I think what made it so unique immediately was, it didn't look like any skate shop before, it looked like an art gallery. You walked in there and the products that they did sell were against the wall in the neatest, most pristine way they could be presented. The skateboards themselves were displayed as if they were pieces of art. The ceiling was really high. You had white walls and hardwood floors. Before then, a skate shop was like a workshop.

It was the sort of place that was dirty, grimy and gritty, and had bearings, trucks, tools and crap everywhere. This was the antithesis of what James Jebbia envisioned for his shop, Supreme. That alone made it really, really different and unique.

James Jebbia is kind of missing from the film. Why did he like to stay behind the scenes?

Well, he's a guy that's wildly private. I think that mystique has been a big part of the magic of the brand. It, in my mind, is incredibly refreshing. It's such a far turn from the culture we currently live in, where everyone's posting every last thing on social media. He just isn't that. He comes from a different time and place, and that mystery behind him really added to the brand, especially as it started to explode as a legitimate fashion house.

It started as a skate shop, but the clothes, the hats, the sweatshirts and all the gear became so coveted that it really became this brand new idea in fashion. The way they released product was trailblazing as well. They would release new capsule collections every week. That drove demand. There was a real supply demand marketing masterclass that was brought into play here, that no one had ever done before.

That just drove people nuts trying to get the stuff. Then this reselling becomes a whole market. It becomes a big explosive business in and of itself. It's not just about getting the stuff, it's about selling the stuff for a profit. There's this micro economy that gets birthed in Downtown New York, that's now global.

It’s interesting, because Supreme's clientele changed over time, and people got used to the drop, buying, and reselling. What does it say about culture, maybe even counterculture, that something so raw and local could become so collectible and commodified?

We've seen it with high-end couture brands, or ladies' handbags. There's certain items over the years where, gosh, if you can get your hands on it at retail, it's just going to go up in value. For that idea to come into streetwear, at the time, was unheard of. Sneaker culture, the proliferation of sneakers, sneaker collecting, and sneaker reselling, and the secondary marketplace also plays a huge role in this, because collaborations come into play, and suddenly, it's not just about Supreme.

It's about Supreme making a Nike Dunk. It's about Supreme Louis Vuitton. It's about Supreme and another great brand coming together to create something that suddenly brings in two different audiences, and then that just drives up the demand to a whole other level. Like I said, it really is like a masterclass in marketing that was birthed at this tiny skate shop in downtown New York at a time where … we think of SoHo, New York, and we see all these stores there, it's kind of like this shopping mecca.

In 1994, it wasn't that. It's hard for people to imagine, but without Supreme, you wonder what SoHo looks like today, I think it looks quite, quite different. I really do.

In the archival footage, we see how dangerous it was to skate in the city at that time. Cars screeching to a halt, people getting beat up for interfering with skating. How did New Yorkers feel about the city skate cult back in the 90s, when it was blowing up?

Yes, I don't think they felt great about it. You're walking down the street, suddenly, four guys are coming at you, or coming from behind you. It's scary. It's daunting to interact in a city where everyone's managing a few square inches as they go about their way. You know New Yorkers. New Yorkers are very emphatic about their right of way and are not the kinds of folks who historically are patient enough to sit and wait if someone does a trick in front of them.

There was this give and take. How do we coexist here? How do we live in a tight space that allows me to get where I want to go, but allows you the freedom to express yourself on your skateboard?

In the '90s, there was a lot of animosity towards these folks. With time, like anything, they became accepted. I think their value, their artistry – just everything they stood for – became celebrated more than disliked or disdained, so, finally, people got on the same page as New Yorkers, like, "Hey, we can make this work."

Even still today, you see skaters riding down a busy street and they're getting flak from passersby. It happens every day, everywhere in the city, still.

Whole Foods is trying to shut down a Bowery rooftop bar The senior crew going on weekly pilgrimages to Queens restaurants NYC art schools see record-high application numbers as Gen Zers clamber to enroll