'A Chorus Line' turns 50: A look at how it changed Broadway forever

July 25, 2025, 5:01 a.m.

You don’t get 'Hamilton' without 'A Chorus Line.'

Friday marks the 50th anniversary of the iconic Broadway musical “A Chorus Line,” which opened at the Shubert Theatre on July 25, 1975.

The story of dancers auditioning for the chorus of a new musical became a singular sensation. The show picked up nine Tony Awards and the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1976. It ran for 15 years – the most performances of any Broadway show up to that time – and had an enormous influence on today’s Broadway, including how musicals are created.

“It really shouldn't have worked on any level,” said theater historian Laurence Maslon, “because it took every convention of the American musical and turned it inside out.”

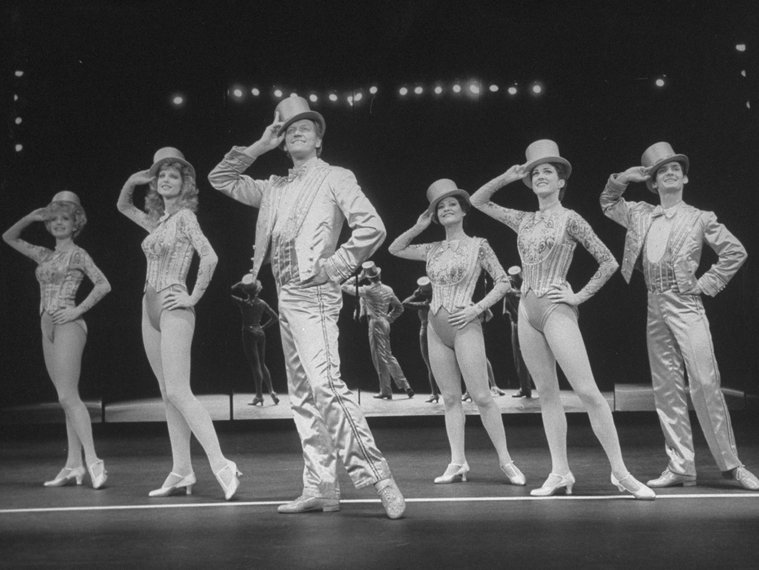

The barebones staging of “A Chorus Line” was novel at the time. When audiences entered the Shubert Theatre, they didn’t see an elaborate set or a red velvet curtain – instead they saw a black box, with a white line at the front, and performers in rehearsal clothes doing a dance routine.

That kind of spartan aesthetic was different from the star-driven musicals of the time, like “Applause,” with Lauren Bacall, or the groundbreaking musicals Stephen Sondheim and Hal Prince were creating, like “Company” and “Follies.”

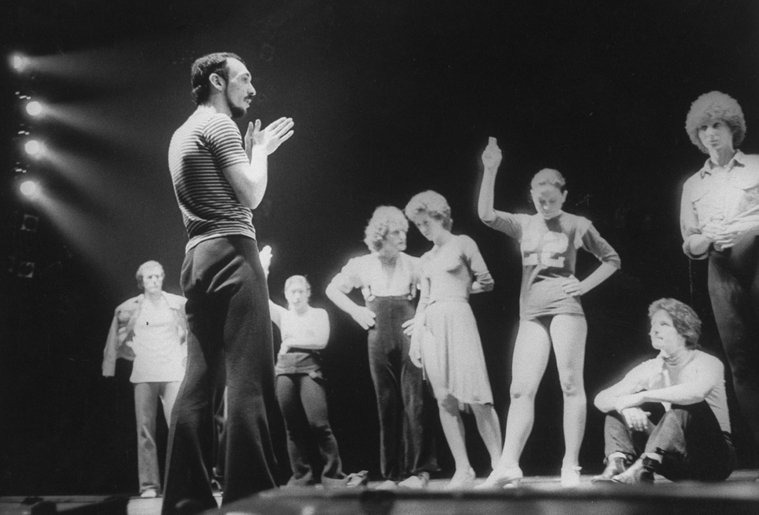

“A Chorus Line” was the brainchild of director and choreographer Michael Bennett, who had worked with Sondheim and Prince on those two musicals, as well as “Seesaw” and “Promises, Promises.”

Bennett gathered some of his favorite dancers in a loft for an all-night rap session which he recorded and used as the basis of the show.

“Everybody was handpicked,” recalled Donna McKechnie, who originated the role of Cassie and attended that fateful jam session on a snowy winter evening on the East Side.

“Michael knew all these people from working with them and he invited people he thought would be interesting,” she said. She recalled sitting on a rug with the other dancers, sharing a big jug of wine, while Bennett started a tape recorder.

“We sat around in a circle like at summer camp or something," McKechnie said. "And Michael said, initially, 'I don't know what this is going to be, if it's going to be a book or a musical. But what I do ask of you is to just speak the truth. Be truthful.'”

And so, he started with three questions that wound up in the Broadway show. The character Zach, the fictional musical's director, asks auditioners on the line: “Just tell me your name, where you're from and why did you become a dancer?"

The dancers told stories from their childhoods. Many had disapproving parents, coped with being gay or dealt with career disappointments. Many of the men, like Michael Bennett, had accompanied their sisters to dance class and shared stories of their awkward adolescence and young adulthood.

Armed with hours of reel-to-reel tape, Bennett approached the Public Theater's founder Joseph Papp and asked if he could keep workshopping his idea, to see if it could become a play with music, or a musical.

Papp – who wasn’t a fan of commercial theater – was intrigued and said yes. “A Chorus Line” was developed over a couple of workshops at the Public Theater.

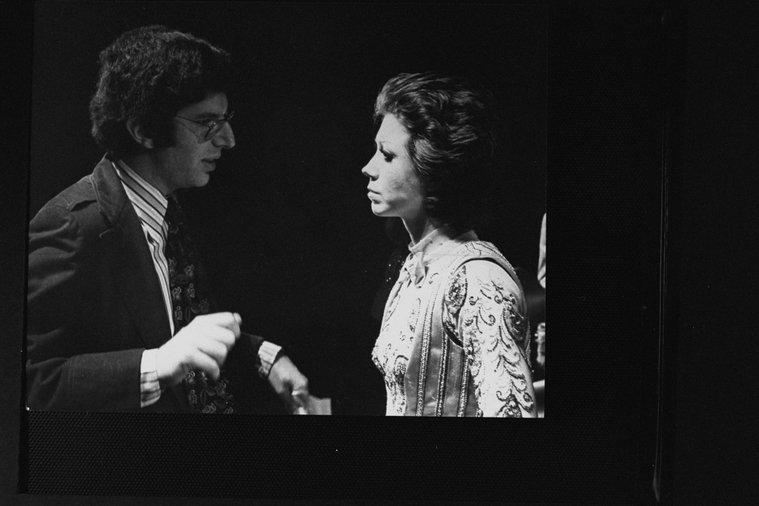

The first iteration was over four hours long. For the second workshop, Bennett brought in composer Marvin Hamlisch and lyricist Edward Kleban, to write the songs. McKechnie recalls the first song the company heard: “At the Ballet.”

“I remember thinking, 'Oh my God, I don't know if this is gonna be commercial, if it's too insular for people; it's a backstage dancer's life.' But this song is so accurate, so perfect and so beautiful, so touching,” said McKechnie. “And I thought, this is going to be a work of art.”

In that second workshop, Baayork Lee, the original Connie, said that Hamlisch developed the show’s extensive underscoring by meeting individually with each of the dancers.

“He'd say ‘just talk’ and he would play our personalities,” she recalled. “So in the show if you hear, every single person has underscoring because you know he was just out of the movies and so he treated this like a movie. We are all underscored with our personalities.”

The run downtown at the Public Theater sold out and the show quickly transferred to Broadway. Lee said the verisimilitude the original cast brought to the show couldn’t be faked.

“We were the first reality show, because we played ourselves,” she said. “And those are our words that were on the tapes. We are authors of the show.”

Back in 1975, the Theater District was run-down and dangerous. There were adult movie theaters, prostitutes and massage parlors in Times Square and many potential audience members stayed away. But the enormous popularity of “A Chorus Line” brought them back to Broadway.

“When I arrived in New York in 1975, two thirds of the Broadway theaters were dark,” remembered Oskar Eustis, the Public Theater's current artistic director. “And 'Chorus Line' started the process of Broadway reviving itself.”

It also changed the way musicals were developed. Before “A Chorus Line,” shows mainly tested and changed their material with out-of-town tryouts, going to Boston, Philadelphia and Washington on the road to Broadway.

But after “A Chorus Line,” many shows opted to do workshops in New York City. Perhaps the most successful show that started in this way is “Hamilton,” which will be celebrating its 10th anniversary on Broadway this summer and which started on the very same stage at the Public Theater.

Eustis said the two shows had many things in common. For both of them, from “literally the first song, the show was a hit,” he said. But the show, he said, “ instantly struck a need that the audience didn't know they had.”

“It took the spotlight off the star and onto the people behind the scenes,” said Eustis. “And it wasn't just a showbiz musical, it was about America needing a job and that the stress and the intensity of that need put all of those things together and weirdly you ended up with at that time the most popular musical America had ever seen.”

Lee, who’s staging a sold-out gala 50th anniversary performance on Sunday at the Shubert Theatre, said this story of dancers vying for an anonymous job as members of the chorus always hits home with audiences – and not just because of its themes of passion and dedication to chasing Broadway dreams.

“You look on that stage, you see 19 characters, and there's somebody in your family,” she said. “And it's not only about singing and dancing, it's storytelling. It's those stories. The alcoholic father, the unfaithful father. It goes on and on.”

The hottest party in New York right now? Labubu raves. A new documentary looks at Supreme and the rise of NYC’s skateboarding scene